Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The internet in everything

Even books are getting in on the act. Amazon's second-generation Kindle ebook reader includes WhisperNet, 3G-based data transmission that automatically downloads content from various sources including newspapers, magazines and blogs.

Its WhisperSync service will apparently enable you to browse the same document across multiple devices and browsers without losing your place. While Kindle is still rather basic, forthcoming ebook devices like the Readius offer similar features, better portability and integrated email and RSS readers for instant access to information no matter where you might roam.

As electronic paper gets bigger and cheaper, there's no reason why we couldn't have internet-enabled display advertising in shops or, in the long term, on the side of bus shelters. Or on the buses themselves, for that matter.

Couch potatoes needn't feel left out. At this year's Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Intel and Yahoo! showed off televisions with 'widgets', which are sidebar Gadget-style applications providing onscreen access to services such as MySpace, Flickr, Joost and the inevitable weather reports and share price tickers.

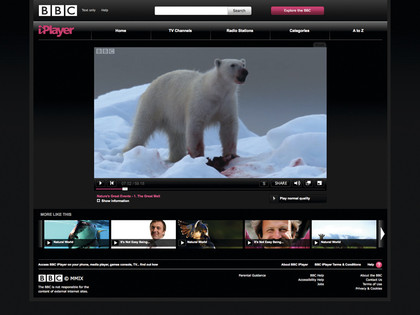

CHANGING TECH: The iPlayer launched less than 18 months ago, but it's already undergoing changes

Intel has carried out lots of research into this area, and found that people didn't want a fully fledged web browser on their TV. What they did want was a way to connect with friends and family, access relevant information and find out more about programmes from the comfort of their sofa. As far as we can tell, they didn't say they wanted more adverts, but of course onscreen widgets will deliver those too.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The internet everywhere

What all these products have in common is the assumption that internet access will be everywhere, either piped into the home or via the mobile phone network. Right now that's rather optimistic – if you've ever tried to get a 3G signal a few miles outside a major city, you'll know what we mean – but by 2012 things should be vastly different.

In February, Motorola began testing 4G LTE (Long-Term Evolution) in Swindon. The firm hopes to have commercial products on sale later this year. LTE is one of two key candidates to replace 3G – the other is WiMax – and it's the most likely to succeed, as it takes advantage of the existing 3G infrastructure.

With speeds of up to 100Mbps over the mobile phone network, 4G sounds great. But when even 3G coverage is currently patchy in rural areas, will many people be able to get it? It's a similar story with wired broadband: even if the recession doesn't force the company to scale back its plans, BT's roll-out of faster internet will only reach 10 million homes by 2012, and Virgin's network upgrade will only affect cabled areas.

The good news is that the government is committed to delivering broadband to everyone in the UK. The bad news is that by 'broadband', it doesn't mean 'fast broadband'. Britain's internet future is outlined in Lord Carter's Digital Britain report, which is currently in the consultation stage. The final report, due this summer, will form the basis of government policy.

One of the key recommendations is that the Universal Service Obligation – which currently compels BT to provide a phone service to anybody who wants one – should be expanded to include broadband. Under the proposals, the entire population of the UK would be able to access broadband services at a reasonable price, either via wired broadband – DSL or cable – or over the mobile phone network.

BLOGS ON THE GO: Amazon's Kindle device takes advantage of constant connectivity by downloading blogs and newspapers via 3G

Expanding the USO to cover connectivity is an excellent idea, but don't expect it to deliver high-speed broadband to every home in the UK. While ADSL, cable and 4G could deliver speeds of up to 100Mbps, the proposed USO will only ask for 2Mbps.

The digital divide

The universal service proposals in the Digital Britain report are relatively uncontroversial, and while the details of how it's going to happen are still being hammered out, it seems likely that by 2012 we will always have access to at least 2Mbps broadband, wherever we happen to be. However, these connections are unlikely to be at all adequate by then: three years is an eternity on the internet.

For example, the BBC iPlayer only went live in December 2007, and it's already undergoing signiicant changes. Even more worryingly, Digital Britain says that the government has yet to see a case for legislation in favour of net neutrality, and there are apparently no plans for the government to invest in high-speed networks beyond BT and Virgin's existing proposals.

Taken together, that means two bits of bad news: there's going to be a digital divide between those of us lucky enough to live within BT or Virgin's high-speed networks and those of us stuck with mobile phone connections. There's also likely to be a two-tier internet where ISPs use traffic management and other technologies to control what you can access – unless you're willing to pay a premium, of course.

That applies to mobile connections, too: with the advent of 3G broadband and unlimited data access plans, mobile operators are already using traffic management to limit their customers' connections. There's plenty more bad news where that came from.

Mobile broadband is expensive, and if pricing is left to the network operators, the promised universal availability of broadband in the UK could be scuppered by excessive monthly or per-gigabyte charges, or by miserly bandwidth quotas.

Historically, mobile phone networks have charged as much as they could possibly get away with. The UK government turned a blind eye to this until the EU Telecommunications Minister threatened to beat the networks with a legislative stick. That's why international roaming charges for voice calls didn't come down until 2007, and it's why text and data roaming charges are finally falling now.

In the Digital Britain report, Lord Carter talks about "reasonable" pricing for universal broadband. That's great, but his definition and the operators' definition of reasonable may well differ from ours. Then there's the issues of censorship and surveillance.

The government is currently considering legislation forcing websites to classify content so that ISPs can ensure children don't access them – something that was tried unsuccessfully in the US – as well as a single central database of all our communications data.

Factor in Lord Carter's proposals that ISPs should be compelled to collect data on alleged copyright infringers so that entertainment firms can sue them more easily, and the future of the internet in the UK appears far from idyllic.

In fact, it looks rather like our creaking transport system: overloaded, prone to jams at the most inconvenient of times and under constant surveillance. Only Britain could take the idea of an information superhighway and try to turn it into the M6.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

First published in PC Plus Issue 281

Liked this? Then check out How search engines are getting smarter

Sign up for TechRadar's free Weird Week in Tech newsletter

Get the oddest tech stories of the week, plus the most popular news and reviews delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up at http://www.techradar.com/register