I tried to electrocute myself fitter

Prepare your body for a shock

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Electricity is an interesting thing. It’s powering the device you’re reading this on right now (unless you’ve printed it off to create your own TechRadar newspaper), but it’s also powering the thing in your head that’s allowing you to understand the words.

Your brain is a gooey ball full of electricity, and when you want to move a muscle in your body, your brain sends some of that electricity down through your nervous system to the muscle, and stimulates the muscle contraction.

Okay, that might not be exactly how a scientist would describe it, because it’s "inaccurate" or "naive to the point of falsity", but who needs those guys? It’s near enough that it makes sense, and I can keep talking.

So… Electronic Muscular Stimulation (EMS) is the technique of using electricity from a device to stimulate your muscles, an ‘outside-in’ method if you will. You can obviously get muscles to respond to electricity – but is it good for you?

From rehab to no-flab

The surprise answer is yes. Well, it can be. If you’ve got the time (and the interest) there are plenty of good Google Scholar articles on the benefits of EMS, but long story short, it was originally used as a method of rehabilitating patients with atrophied muscles.

Of course, what makes a muscle grow for someone post-injury is also going to make a muscle grow for someone who wants to look hella-jacked, so it wasn’t long before the fitness industry caught on, which led to devices like Slendertone and this:

Exercise and electricity are both potentially dangerous on their own, so if I was going to combine the two I thought I’d save myself some risk (and save my sofa from getting sweaty) by going to an EMS gym.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

These gyms are starting to pop up all over the world, and they promise to get you fit in 20 minutes of exercise a week. Yes, you read that right: 20 minutes a week.

The principle is simple. You start by getting strapped into a suit that looks like this:

It’s got electrodes all over it that line up with your neural pathways, so that rather than just stimulating a single muscle belly (that’s what it’s called, don’t blame me), the suit can stimulate an entire muscle chain, meaning you get greater engagement from your muscles.

You’re then led through a series of exercises that would be easy if you weren’t being electrocuted, but while you’re being electrocuted. So not only do you have to think about your form for your squats, you have to try to stop your legs from involuntarily doing the can-can underneath you.

There are different levels of intensity that your PT chooses for you, and you can really feel the difference when the intensity level goes up. It’s like being stuck inside your own reanimated corpse, wearing a superhero costume, doing squats, in front of someone who is fitter than you will ever be.

DOM DOM DOMS!

If that sounds bad, it’s nothing in comparison to the pain you’ll feel in two days' time when the ache sets in. One day after is painful; two days after, you can barely move.

The reason for this is actually really interesting from a biological point of view. When you stimulate a muscle externally, you activate the entire muscle, causing micro-tears (they’re a good thing) in all the elements of your muscle fiber.

Given the amount of (positive) muscular damage that you’re doing, it’s easy to understand how you could maintain a low level of fitness with a single session a week – I know I wouldn’t be keen to do more than one session a week.

If you’re interested, I went to a gym called Surge, but there are EMS gyms popping up all over the place. You’ll still have to eat well, but if you’re looking for a way to achieve big goals with minimal effort, an EMS gym might be for you.

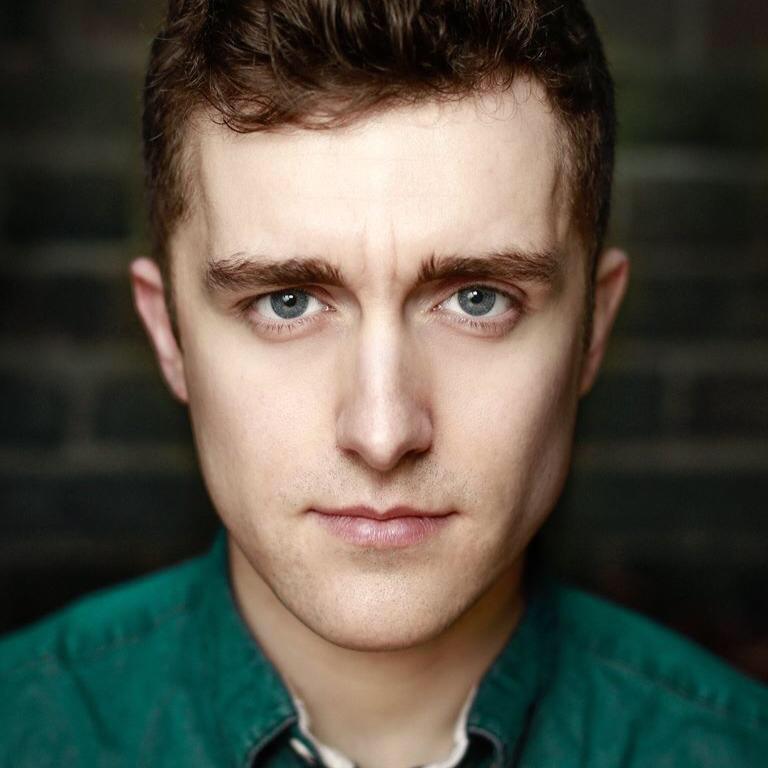

- Andrew London is a laughable excuse for a human being, barely held together with string and sticky tape. In Tech Yourself Before You Wreck Yourself he will be sharing with you the different technology that he uses to try to pass for a proper functioning person.

Logo design courtesy of FreePik

Andrew London is a writer at Velocity Partners. Prior to Velocity Partners, he was a staff writer at Future plc.