A helicopter for Mars and four other audacious concepts for space exploration

From drones and comet-scrapers to space condos

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Not even 12 miles. That's how far NASA's beloved Curiosity rover has traveled across the surface of Mars in its six years at the Red Planet.

It's time for a marscopter.

NASA has announced that a Mars Helicopter, a small autonomous rotorcraft, will travel with the agency's Mars 2020 rover mission as a demonstration experiment of heavier-than-air vehicles on Mars.

However, heavier-than-air has a very different meaning on Mars, which has a much lower atmospheric density than Earth.

“The altitude record for a helicopter flying here on Earth is about 40,000 feet," said Mimi Aung, Mars Helicopter project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). "The atmosphere of Mars is only 1% that of Earth, so when our helicopter is on the Martian surface, it’s already at the Earth equivalent of 100,000 feet up."

Firstly, that's meant shrinking the Mars helicopter to a little under 4 lbs./1.8 kg.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Secondly, it’s twin counter-rotating blades will attempt to cut the thin Martian atmosphere at just shy of 3,000 rpm, which is about 10 times the rate of a helicopter on Earth.

“To make it fly at that low atmospheric density, we had to scrutinize everything, make it as light as possible while being as strong and as powerful as it can possibly be," said Aung.

However, the Mars Helicopter is not the only audacious concept for space exploration. In fact, it's not even the only drone destined to explore another world.

Look, no joystick

The Mars Helicopter will be a 'high risk' experiment attached to the belly of the Mars 2020 rover, which is expected to leave Earth in July 2020 and reach Mars in February 2021.

“We don’t have a pilot and Earth will be several light minutes away, so there is no way to joystick this mission in real time,” said Aung. “Instead, we have an autonomous capability that will be able to receive and interpret commands from the ground, and then fly the mission on its own.”

It's only a 30-day test, to include up to five flights from three meters to up to a few hundred meters, and only for between 30 and 90 seconds. If it works well, it could quickly become a standard issue instrument on Mars missions.

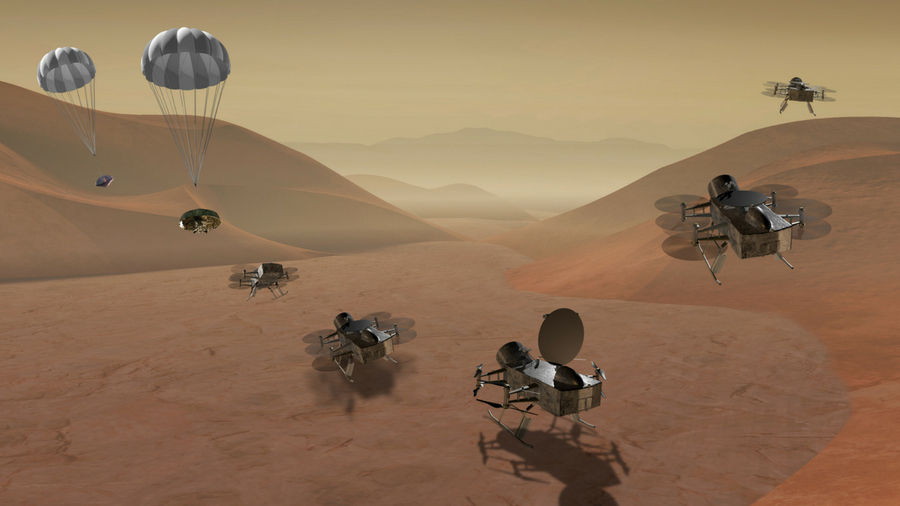

Dragonfly: Titan Rotorcraft Lander

While flying in the thin atmosphere of Mars is a real technical challenge, the same is definitely not true of NASA's other proposed exploratory helicopter.

A competitor within NASA's New Frontiers Program, Dragonfly will have no trouble at all keeping buoyant in the dense atmosphere in Titan, where even a human could fly just by flapping their arms.

A high priority for planetary exploration (though any attempt to stay on Titan would require new technology), Saturn's largest moon has been landed on once before, in 2005 by the Cassini spacecraft's tiny Huygens probe.

It took some spectacular footage and sent back a few atmospheric measurements, but the mission only had the battery power for 2.5 hours of data transmission. Huygens remains the most distant lander ever launched from Earth.

The two-year mission plan for Dragonfly would see it touch-down on a vast black sand dune where a safe landing can be assured, to take measurements of the weather, temperature, seismic activity.

That data alone will vastly increase astronomers’ knowledge of Titan, but Dragonfly will then take a flight every 16 days to another area, perhaps tens of kilometres away.

It's risky, because Dragonfly won't know much about what it's going to land on, but it will be vastly more mobile than any planetary rover. If selected by NASA, Dragonfly would launch in 2025 and reach Titan in 2034.

Aurora Station's 'orbital property'

Want to see the Northern Lights … from above?

If so, you'd better act fast because US space company Orion Span's proposed luxury space hotel is already booked up for its first four months.

Those with an US$80,000 deposit can guarantee their spot on Aurora Station, which is slated to host its first guests in 2022. However, it gets a little more expensive than that, with a standard 12-day journey actually costing US$9.5 million per person.

Designed as the first fully modular space station, Aurora Station will host six people simultaneously, including two crew members.

Once up there, space tourists will get to see the Northern Lights and the Southern Lights through the space station's many windows.

They’re unlikely to get bored; Aurora Station will sit in a low-Earth orbit 200 miles above the Earth's surface, traveling around the globe once every 90 minutes. That means about 16 sunrises and sunsets in every 24-hour period.

However, if that does get dull, there will also be VR headsets and high-speed wireless internet access available for live streaming back to Earth.

We will later sell dedicated modules as the world’s first condominiums in space … future Aurora owners can live in, visit, or sublease their space condo

Orion Span CEO Frank Bunger

Though it's easy to scoff at projects like the Aurora Station, the International Space Station's long-term future is in doubt, and projects like these could prove invaluable to state-owned space agencies to conduct a zero gravity research on a lower budget.

As well as taking up space tourists and professional astronauts, the designers of Aurora Station intend not only to grow its size quickly, but also to begin selling ‘orbital property’.

"Our architecture is such that we can easily add capacity, enabling us to grow with market demand like a city growing skyward on Earth," said Frank Bunger, CEO of Orion Span. "We will later sell dedicated modules as the world’s first condominiums in space … future Aurora owners can live in, visit, or sublease their space condo." Expect astronomical prices.

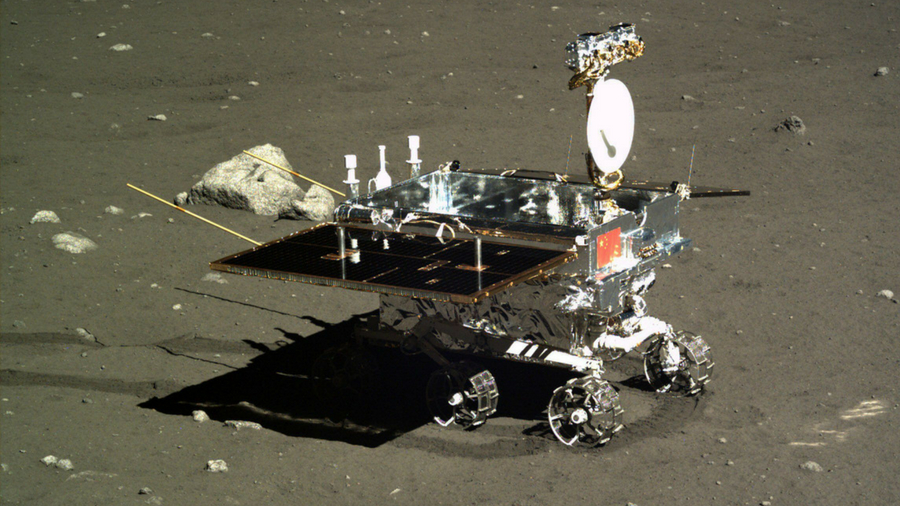

China's Lunar Palace

The alarming uncontrolled de-orbit of its Tiangong-1 space station could be the last time anyone views China's space policy with anything but envy.

Having landed its Chang'e 3 probe and Yutu rover on the moon in 2013, China looks set to send Chang'e 4 to the far side of the moon later this year, specifically to its South Pole, which may contain the water required for a lunar base. And that's exactly what China is planning.

It appears that China's National Space Administration has ambitions to both explore the moon and use it as a launchpad for manned Mars missions.

"We believe that the Chinese nation's dream of residing in a 'lunar palace' will soon become a reality," the administration said in a video, reports China Daily.

This manned scientific research outpost on the moon could have multiple tube cabins that interconnect and provide oxygen to people inside.

One of the facility's major energy sources will be solar power, according to the video, though it also mentioned the exploration of the moon's North Pole as well as its South Pole.

With NASA seemingly unable to produce any momentum or funding for a return to the moon, it seems that lunar exploration will be left to China. However, there are suggestions that the proposed 'lunar palace' could be constructed with the help of the European Space Agency (ESA).

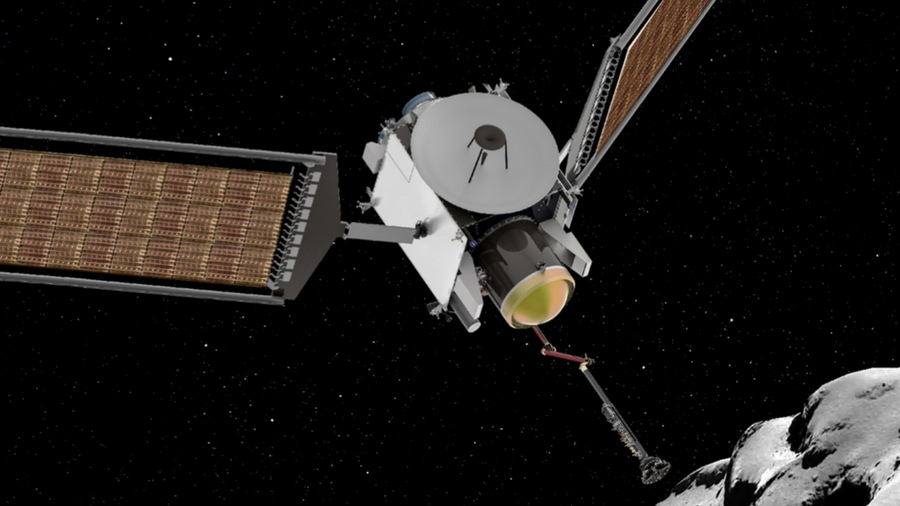

The CAESAR comet-scraper

Remember the ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft and the plucky lander Philae that bounced into a shadow and died on a comet? It's time to go back.

Declaring the target – 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko – worth investigating again is a team from Cornell University, whose proposed Comet Astrobiology Exploration Sample Return (CAESAR) mission wants to determine its origin and history by collecting 100g of samples and returning them to Earth.

It's the latter objective that has surely sparked the interest of those at NASA, whose New Horizons team currently has its OSIRIS-REx spacecraft on the way to do a similar job at the asteroid Bennu. It will reach its target in December this year, and attempt to return a sample to Earth in 2023.

Scheduled for launch in 2024, the solar-powered CAESAR's samples wouldn't arrive back on Earth until 2038. However, the samples would be more highly prized; comets are made up of materials from ancient stars and interstellar clouds.

Getting a sample of a comet to study would give astronomers insight into how these materials contributed to the early Earth, including the origins of the Earth's oceans, and possibly of life itself.

- Take flight with the best drone 2018!

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),