Motion sickness and double glazing: the challenges of developing a game for VR

PC Gaming Week: 10 developers dish on how to do VR gaming

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Some scoff at virtual reality. Anyone who lived through the previous VR 'revolution', who saw devices like the Virtua Boy or sat in a Battletech pod, is skeptical.

By contrast, many who've used the flagship modern devices - the HTC Vive or the Oculus Rift - are evangelical, and think VR will change lives now.

Then again, others think that virtual reality is going to be another mobile phone-driven revolution that will take another 10 years to bed in, and will be more about augmented reality, changing the world we see around us digitally.

To temper our expectations, we spoke to 10 developers at Ndreams, one of the premier VR developers, which is working on what it sees as a AAA VR game, The Assembly. From what we've seen, it's a glossy, strange and English thriller, evocative of John Wyndham and J.G. Ballard.

Get lost in the world

Apparently for developers, the first step in designing a VR game is to embed yourself in the experience. "Close your eyes" says Jamie Whitworth, The Assembly's Lead Designer. "VR is about immersion, there is no outside world, so there shouldn't be one when you're designing. Then, you imagine your controllers - remember you can't see them by default and keep that in mind forever.

"Only then do you start filling out the play-space in your imagination, from the environment, through to your means of interacting with it all the way through to your place in the world."

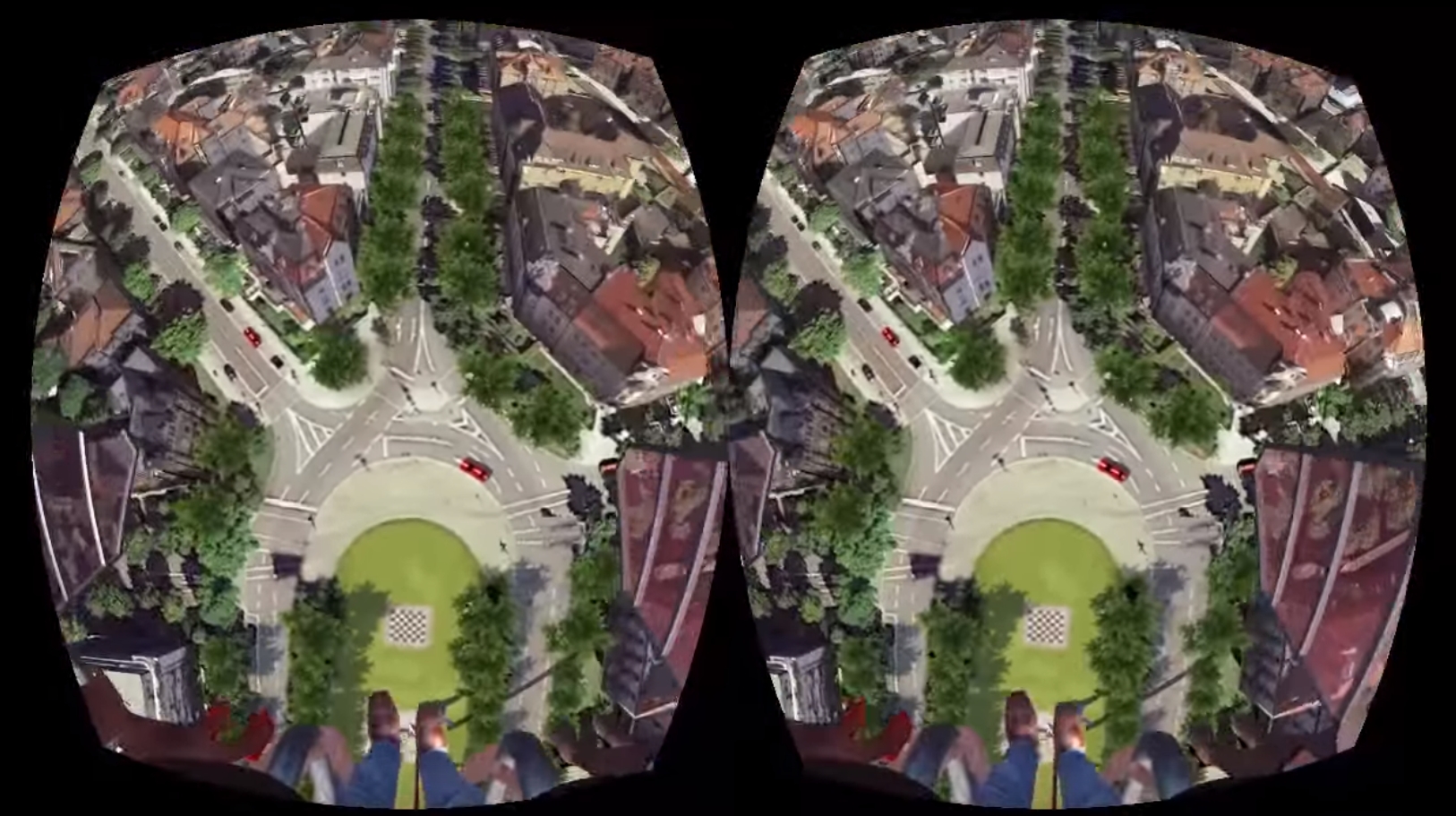

At this stage, you also need to decide how you're going to present the world to the player, whether their camera is "first-person at natural head height, or makes them feel like a God with an aerial perspective, or reaches for the surreal with more fantastical solution."

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

As Whitworth puts it. "All design is the planning behind the creation, and VR gives you a wholly different set of parameters to play with."

In The Assembly, the choice was taken to make a first person game, from two different character viewpoints, with an unusual blink movement system - Ndreams worked out that instantaneous teleportation was yet another cause of motion sickness, so they instead move the player between areas at roughly 100,000 miles an hour, which apparently allays the problem.

"Of course, you also have to constrain yourself with technical details and identify the properties of the hardware you are targeting – whether that's tethered or mobile VR." says Jackie Tetley, Senior Designer.

"Different VR platforms have different considerations to bear in mind - for example play session length, control devices, face-forward or walk-around."

The best of the best

Once you've established your concept and design limitations, you need to assemble your team. Team sizes are comparable to equivalent non-VR projects, but the balance of specialisms is different, with more programmers, designers and performance specialists and fewer engineers.

But are there new specialisms in the team, expertise hitherto unforeseen in game development to deal with this new platform of gaming?

Well… no. According to Tom Gillo, the VP of Development, the team needs "the same qualities that anyone working on ground-breaking and previously untested hardware platforms have always needed: the ability to embrace the challenge of conquering the unthinkable, to be unfazed by the seemingly impossible, the ability to thrive in adversity and revel in solving the unsolvable.

"If you don't enjoy a little chaos or are intimidated by tackling the unknown, get irritated by moving goal posts or get too exasperated by infant technologies that just won't behave, then working in VR probably isn't for you."

You also need to outfit your team with the right kit. Given VR's early adopter status, this might be rather expensive. "Realistically?" Says Fabian. "We get the best toys so that we can do our job. That means key devs get Titan GFX cards, which is lovely.

"In terms of the studio environment, we need more space than a regular game dev, 'cos otherwise we'd literally be tripping up over each other's cabling."

And that's if you can get hold of the various developer kits or afford to pay for them - the Microsoft Hololens developer kits, for example, are $3000 (around £2160 / AU$4000) each.

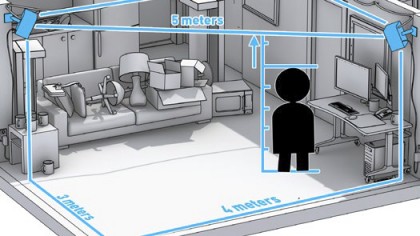

Apart from their desk kit, Ndreams also has a full test room, to replicate the consumer experience. "Our current setup is in an empty room, (save a desk, chair, PC and HTC Vive) that is 3.9m wide and 4.4m long," says George Kelion, Communications Manager.

"The minimum required space is 1.5m x 2m and the maximum is 5m x 5m. In our experience the more free space, the better."

So you're a game developer and have a concept, a team and the hardware. Now you have to get down to making the game. Yet, again, nothing here is quite as it is in normal development. For example, player behaviour is different, especially in an exploration game like The Assembly.

"We had to consider that people will spend less time manoeuvring and more time inspecting the world," explained Dan Chambers, Designer "so we aimed for smaller environments with a richer level of detail. This is especially important given the challenges of motion sickness in VR.

"It's also important to consider that real-world phobias like heights and darkness are more impactful when you have a sense of presence in the world, and thus we had to be careful not to overwhelm the player."

That sense of visual environmental detail has to be matched by other elements. For example, the audio effects need to bolster that immersion.

"On one hand we have the benefit of positional audio technology," says Matt Simmonds, the Audio Director, "but we also need to focus more on detail in sounds to make objects feel believable in a 3D space."

So, in The Assembly, leaning your head inside a fridge, say, will alter your perception of sound to reflect the object's properties, amplify the appliance's hum, and so on.

Oddly, Simmonds has found that music doesn't detract from the experience, as you might expect when attempting immersion. "It depends on the game of course, but we haven't had a problem with using music in a traditional manner for narrative-based games.

"Having music that follows the player around doesn't feel weird in VR; in fact it can help to connect the player emotionally with the space they're in."

One thing does intrude, as Assistant Producer Dan Mills attests - ambient noise. "If you're not using isolating headphones then double-glazing is an absolute must."

Still stuck in Uncanny Valley

Once you've created this hugely rich world, your humans better had match up too. The uncanny valley - that region of animation that becomes disturbing because it's too close to reality - is a constant threat. "We are most certainly not through the uncanny valley," says Martin Field, the Art Manager.

"If anything, VR emphasises and amplifies any differences. Lip-syncing and realistic animations are even more important in VR than for flat-screen games, as there's so much scope for spotting something that will break your immersion and pull you out of the experience."

With these levels of audio, visual and even proprioceptive stimuli, the biggest problem these VR developers face is one that predates the written word: getting the consumer to listen to the storyteller.

But all these rich elements can be used to lure the player's attention, as Steven Watt, the Design Manager explained.

"You need really good signposting as you cannot guarantee which direction the player is looking. For example, cut-scenes are impossible to implement in a traditional style, as taking control of the camera away from the player is prohibited, lest it induce simulator sickness.

"To overcome this we utilize techniques such as audio cues, lighting, animation, gaze detection and micro-stories – e.g. small sequences of events that the player can't help but notice and which capture their attention effortlessly."

And, finally, no matter how you prepare, VR is a new field so always throws up the unexpected. As Fabian puts it: "None of us really expected that we'd need to learn so much about human physiology. How and what we perceive, how they combine, and why we need to treat them as a single target when designing so as to avoid dissonance and discomfort."

One thing everyone can agree on is that there's much learning still to be done. These early applications could be paralleled with the Lumières' The Arrival of the Mail Train, utterly impressive when shown in the late 1800s (the audience reportedly panicked with the large train coming towards them on the screen), yet where the media creators are still testing the basics of their techniques for presentation and communication.

Like all VR developers, The Assembly team are still working out how these machines work, step by mistep. One thing is certain; a VR simulation today is going to be unrecognisably primitive compared to one in half a decade's time.