Foley: the art of movie sound effects

A look into an unsung artform

While people are quick to praise a film's cinematography, music, special effects and editing, the art of sound effects creation, or Foley, usually goes unnoticed.

However, unlike those other aspects of filmmaking, Foley artists don't want their work to stand out – their work exists to convince you that a film's sound effects were captured on location. You're not supposed to realise that what you're hearing is often something completely different to what you're seeing – you're simply supposed to believe it.

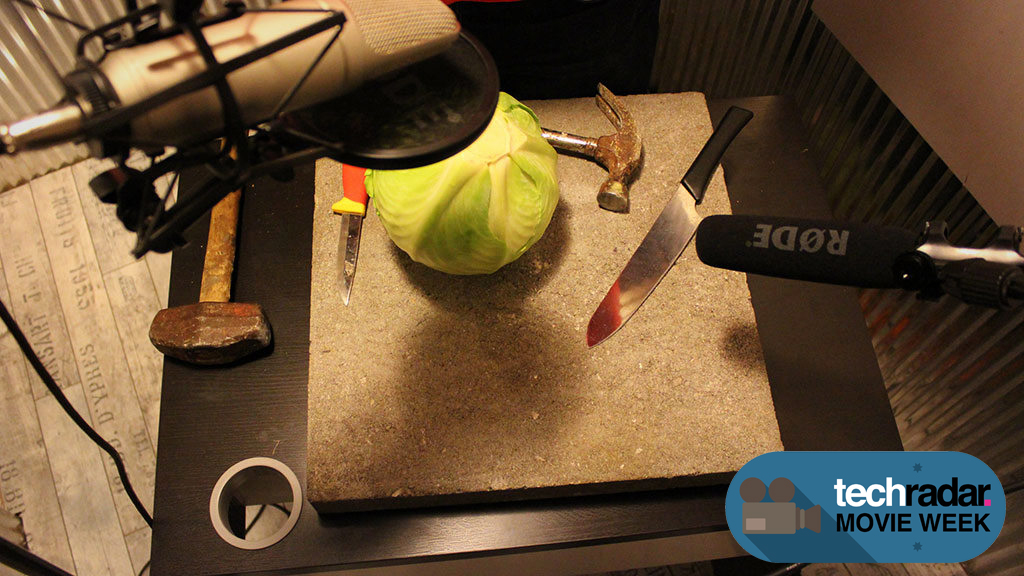

Think you're hearing someone getting punched? It's likely just the sound of some lettuce being head-butted. What about the sound of a horse's galloping? Nope – a Foley artist, sitting on his or her knees, created that effect by rhythmically smacking a pair of empty coconut shells on a shallow pile of dirt.

Whether it's the sound of a sword being unsheathed or swiped through the air, or someone walking through snow, or even a nose being broken, a team of Foley artists created those noises from the confines of a small studio, long after the film's principal photography has been completed.

Quite frankly, foley artists are audio magicians.

Humble beginnings

Dating back to the silent film era, Foley work started out as a way to bring live environmental sound effects to broadcasted radio dramas – after all, we can't actually throw a radio announcer down the stairs (as much as we'd sometimes like to).

The artform was named after its pioneer, Jack Donovan Foley, who worked in the radio industry for years before eventually being hired by Universal Studios in 1914. Though Foley was brought on early by the film studio, his enormous contribution would not be felt until the late 1920s.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Foley's work would eventually take off in Hollywood after the release of the Warner Bros. film The Jazz Singer in 1927– officially considered Hollywood's first 'talkie'.

It was the studio's first ever film to include synchronized sound, used mostly for dialogue – up until this point, sounds in films were a rarity. Most times, the sound effects you'd hear during a film came from an in-house person performing a small range of sound effects during the feature presentation.

While The Jazz Singer was not the first film to boast recorded sound, it was the first to feature synchronized singing, speech and music. This made it technologically superior to D. W. Griffith's 1921 film Dream Street, which employed a phonograph-based sound-on-disc system called Photokinema to produce crowd noises and a singing sequence. In other words, the bar had been raised, and the other studios would have to up their game.

Spurred on by Warner Bros. success with The Jazz Singer, Universal Studios put out a call for any of its employees with radio experience to come forward and salvage its already-completed silent film, Show Boat. Jack Donovan Foley would answer that call, helping turn what was originally a silent film into a proper musical.

While the dialogue was easy enough to record during the film's shoot, environmental and ambient sounds were another matter entirely. Knowing that sound effects could not be accurately captured during filming, Foley and his team decided to project the film and record themselves performing live sound effects, perfectly-timed to actions occurring on-screen. They had to do this in a single take and on a single audio track – there was no room for error.

Modern day maestros

While recording technology has vastly improved since then, the basic principles of Foley work remain the same today.

Sound effects are still created by people using a range of props and their own bodies, though they can be recorded as many times as necessary and synchronized with the film at a later time by a sound engineer.

Modern films also have a huge library of stock sound effects to pull from.

The following excerpt from the 1979 short documentary Track Stars: The Unseen Heroes of Movie Sound demonstrates how frantic the process used to be in its early days. Foley artists would need to have all their props prepared and create sound effects for entire scenes in real time.

Foley in practice

It's possible to separate the creation of movie sound effects into three distinct categories – feet, cloth and props.

A large part of the Foley process involves mimicking the footsteps of the characters on screen. Different kinds of surfaces are employed to create desired sound effects, from concrete and marble slabs to boxes full of dirt and twigs. Footstep pressure is also important, as the difference between a light tread and a loud stomp is quite significant – the pressure has to be just right, so as to not become noticeable.

It's not just about mimicking what's on screen, either – Foley artists will often be called upon to maintain the pace of a character's footsteps while they're off-screen, making it especially tricky to time the steps between shots.

The recording of cloth sounds, on the other hand, is a much rarer occurrence and is generally done so at the discretion of film's sound engineers and director. As you'd expect, the effect is achieved by rubbing fabrics together in front of a microphone. Clothing sounds are generally only utilised when the handling of clothes is focused on in a scene, or if characters brush past each other.

Pretty much every other sound effect in a film is achieved with the use of props. Foley masters must come up with ways to recreate sounds in a practical sense. For example, a bone-breaking sound effect can be made by snapping celery sticks in half. And, rather than set fire to a recording studio, cellophane can be used to mimic the sound of a fireplace.

The video below demonstrates how Foley artist Dennie Thorpe created the slimy raptor egg hatching sound effects in the film Jurassic Park using ice cream cones, rubber gloves and various types of fruit.

Here's another video which shows us how Foley artist Gary Hecker created the sounds for director Ridley Scott's adaptation of Robin Hood. It's an eye (and ear) opening look at how various layers of sound must come together to make a scene come alive.

These are just some examples of how important Foley artists are to the filmmaking process. All of their efforts go towards maintaining the illusion of what is happening on-screen, and to make the audience completely unaware of their presence – If you're noticing the Foley work in a film, it's because it wasn't done well enough. This is why the Foley artist will always be the unsung hero of cinema.

- TechRadar's Movie Week is our celebration of the art of cinema, and the technology that makes it all possible.

Stephen primarily covers phones and entertainment for TechRadar's Australian team, and has written professionally across the categories of tech, film, television and gaming in both print and online for over a decade. He's obsessed with smartphones, televisions, consoles and gaming PCs, and has a deep-seated desire to consume all forms of media at the highest quality possible.

He's also likely to talk a person’s ear off at the mere mention of Android, cats, retro sneaker releases, travelling and physical media, such as vinyl and boutique Blu-ray releases. Right now, he's most excited about QD-OLED technology, The Batman and Hellblade 2: Senua's Saga.