Revolution’s tonal turmoil from Beneath a Steel Sky to Broken Sword

Make 'em laugh

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In difficult or overwhelming times in my life I will inevitably turn to one of two places: my Harry Potter books or my collection of classic point-and-click adventures.

Though it’s not a productive coping method, without fail I come away from my regression feeling safe, rejuvenated and ready for anything. Especially box puzzles.

My most recent grab for my nostalgia blanket found me holding Revolution Software’s Beneath a Steel Sky.

Revisiting the Revolution

Beneath a Steel Sky is a game that I revisit less than Revolution’s other titles and it’s one I would never have discovered if it hadn’t been included for free in one of the many Broken Sword bundles I’ve purchased over the years. However, it’s the perfect scratch to a science fiction itch I’ve been feeling recently.

The game is set in what is apparently a post-apocalyptic Australia and tells the story of Robert Foster. He is, in case you’re wondering, indeed named after the beer. After a helicopter crash left him orphaned and stranded in the Outback (known in-game as The Gap), Foster was raised by a group of Aboriginals who taught him engineering and survival.

When the game begins, a security force from the dystopian metropolis Union City destroys Foster’s village and takes him prisoner. Before landing in Union City there’s yet another helicopter crash which enables Foster to escape into the city. Foster’s incredible resistance to helicopter crashes is never really explored in the game, which is a shame because it’s pretty astonishing.

There’s no denying that Beneath a Steel Sky has a dark and clever story that fits comfortably into the science fiction and cyberpunk genre. Between my most recent playthrough of Beneath a Steel Sky and my last I’ve read a lot of science fiction novels and it’s easy to see where the game uses classic tropes and themes from the genre.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Some of the literary staples of the science fiction genre, from Neuromancer to Gateway, were penned in the 70s and 80s when the excitement of the Space Age was fading and the rise of consumerism and conservatism were resulting in class division evolving in unfamiliar and frightening ways.

Science fiction offered concerned novelists a way to discuss the social divisions of the present by extrapolating them into a future where objectivity was more possible and political umbridge less likely to be taken.

Tonal trouble

Being written in 1980s Britain, Beneath a Steel Sky had more than enough social division to draw inspiration on and it puts an interesting spin on the ‘split city’ trope by having the poor living in Union City’s heights with the factories, while the rich occupy the unpolluted lower levels.

However, though Beneath a Steel Sky has a story with dark and clever potential it also has a sharp and sometimes crude sense of humor. Sometimes this works and sometimes it doesn’t.

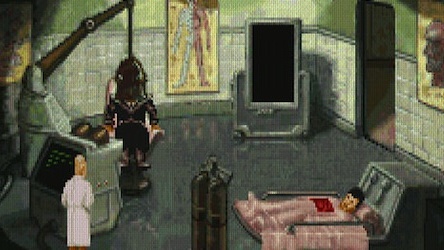

While the game explores social divisions, the rise of corporatocracy, murder and human experimentation, it also takes every opportunity to make the player laugh with puns and quips of varying degrees of subtlety.

There was apparently some disagreement between Steel Sky’s writers Charles Cecil and Dave Cummins about the game’s tone and to what extent it should lean towards serious or humorous. When you play it knowing this, it’s kind of obvious. Beneath a Steel Sky was only Revolution’s second point-and-click game so naturally the studio was still experimenting with its tone and identity.

The writers agreed that they’d like like to find a balance between the earnestness of Sierra’s games and the slapstick of LucasArts and though with Broken Sword it’s clear this balance was struck, with Beneath a Steel Sky they’re definitely still trying to find it.

If anything it’s an interesting look at how Revolution has come to be what it is and I love that you can see a developer evolving through its games.

Though it might not have been the intention, I like to see Beneath a Steel Sky as a kind of science fiction satire. It’s clear Cecil and Cummins loved their source materials but ultimately I’m glad they weren’t shackled by them and injected a lighter tone. After a while, classic science fiction’s unwillingness to poke fun at itself becomes exhausting.

Admittedly, some of the game’s jokes miss the mark entirely and feel like they’re being delivered with an elbow to the ribs from that annoying uncle at a wedding who needs the validation of your chuckle no matter how unconvincing or undeserved it is. In the grand scheme of things, though, I can forgive that.

Beneath a Steel Sky is a good example of the perilous gap that exists between developer intention and player perception and I think Revolution should be praised for how it attempts to bridge it.

Steel Sky tells a story that’s dark enough to provoke thought, but it doesn’t exhaust you with a preaching need to be taken seriously. In a puzzle game, themes aren’t the thing I want to struggle most with - puzzles are.

Its occasional flippancy and humor, then, is what keeps the game from becoming a slog. A game where the story is doom and gloom, the puzzles are hard, and you’re made to feel hopeless about your social and political present and future isn’t one I would associate with the Revolution Software I've come to love.

There’s undoubtedly a place for that, particularly now that the medium is in more of a position to challenge player expectations, but for a relatively new studio in late 80s Britain, I imagine trying to find a balance between your two successful rivals was a more rewarding path to take.

That said, now that Revolution has matured and developed as a company and the gaming landscape has changed since the time Beneath a Steel Sky was first released I’d be interested to see not a remaster of this game, but a sequel. It’s something Revolution is rumored to be working on so fingers crossed we one day see it.

- Emma Boyle is taking a look back at games gone by (some of them older than she is.) Follow her time traveling adventures in her bi-weekly Retro Respawn column. Got any games you'd especially like to see her revisit? Let her know on Twitter @emmbo_

Emma Boyle is TechRadar’s ex-Gaming Editor, and is now a content developer and freelance journalist. She has written for magazines and websites including T3, Stuff and The Independent. Emma currently works as a Content Developer in Edinburgh.