Opinion: the EU's Copyright Directive isn’t just bad for memes – it makes Big Tech even harder to beat

If we want to hold the tech giants to account, the internet needs to stay competitive

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

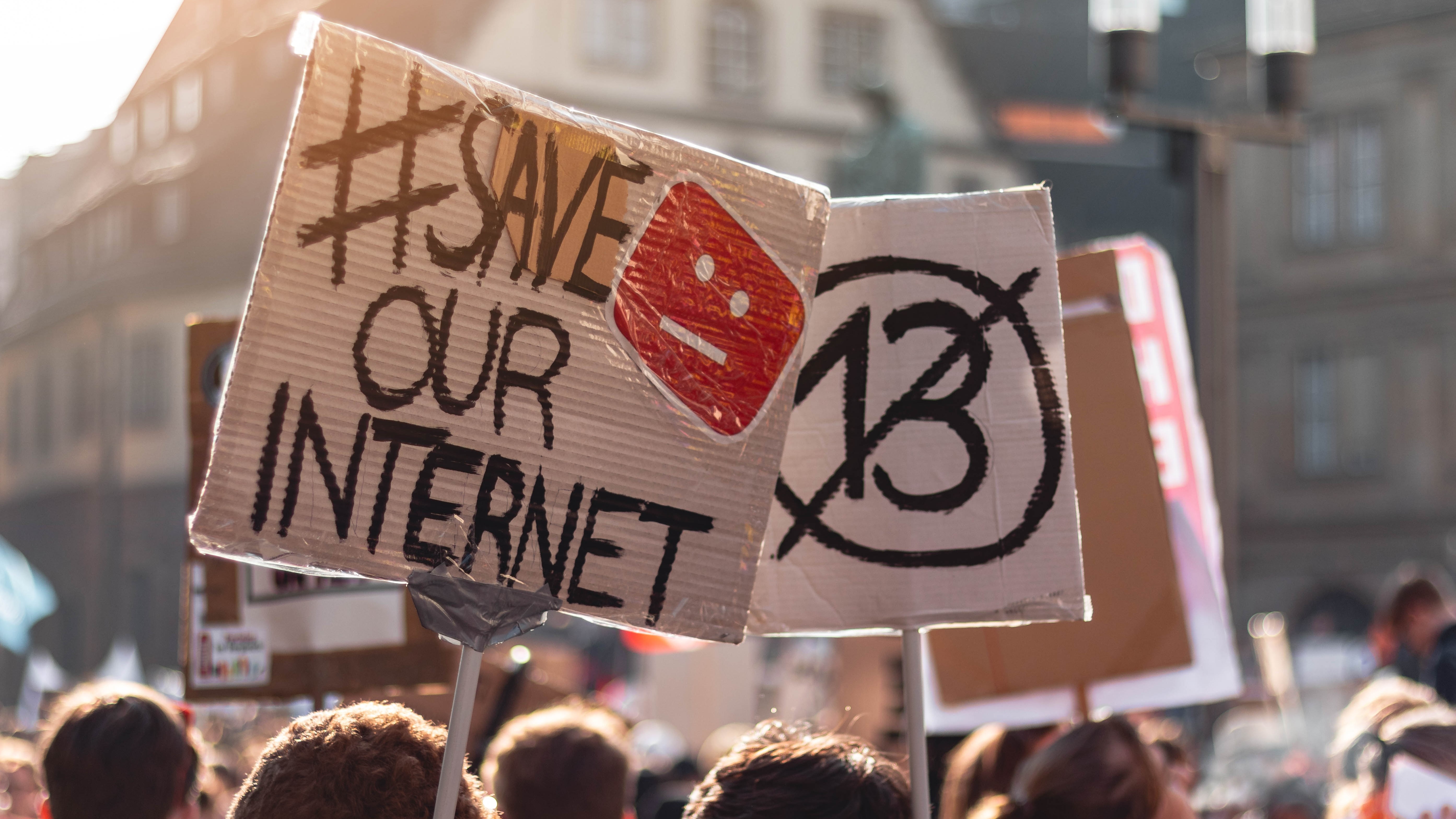

The European Union has long been a shining symbol of freedom and progress, but earlier this week, the European Parliament finally voted in favour of a new set of controversial copyright rules, which according to some critics could lead to the one thing we all feared most of all: Europe banning our right to meme. In other words, the EU became the ultimate milkshake duck.

The big problem with the new directive was Article 13, which confusingly became Article 17 in the final draft. The upshot of the legalese is that it essentially transfers the responsibility for copyright infringement from individuals to the social media platforms that host them.

For example, at the moment if you were to upload Avengers: Infinity War to your YouTube account, it would be you alone who is legally liable for having done so without permission. Under the new rules, however, the burden is also put on YouTube itself, meaning that Disney’s lawyers could start licking their lips in the direction of Google too.

On the surface, this might sound sensible: Who can begrudge copyright owners from controlling where their content appears? The problem though – as demonstrated by the talk around memes – is that it flies in the face of the long-standing ability of the internet to retool and remix images, music, video on social media, taking advantage of the legal grey area that exists at present. While you may be caught and told to take down your video, platforms are happy to take the risk on letting you upload as ultimately, they won’t be paying the price.

The EU, for its part, has pushed back on the specific worry about banning memes, saying that the law “sets strong safeguards for users, making clear that everywhere in Europe the use of existing works for purposes of quotation, criticism, review, caricature as well as parody are explicitly allowed”.

But many prominent internet figures, such as web inventor Tim Berners-Lee, and Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales do not appear convinced – and have spoken out in opposition to the new rules, which are now set to be adopted and written into domestic law over the next few years by national Parliaments – including Britain, Brexit or no Brexit. Even if the law does have a generous interpretation that allows for parody and remixes, what is clear is that by virtue of the new directive existing at all, it’s another hurdle for remixers and meme creators to worry about.

But leaving aside the fate of our memes specifically though, the new rules have another big consequence: They further entrench the power of the existing Big Tech platforms.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Big tech, big problem

The way a market should work is pretty simple on paper: companies sell products or offer services, and if another company comes along that can make better products or offers better services, it will steal business from its competitors. The competition is a good thing, as it will encourage all of the businesses to improve their products to compete – ultimately resulting in better and cheaper products for consumers. Brilliant!

Unfortunately, the real world is more complicated, and one sector where this dynamic is increasingly broken is in the technology space. We all intuitively know the companies we’re talking about: Google, Facebook, Amazon and Apple.

The problem with these companies, argues Paul Mason in his book Post-Capitalism, is that these companies that primarily build their businesses based on the hoarding of information tend towards monopoly. Why? Because the more of your friends who are on Facebook, the more useful Facebook becomes. The more companies that are selling on Amazon, the more useful Amazon becomes, and so on. A new company might offer a better experience or more emojis than Facebook, but ultimately you’re not going to make the switch unless all of your friends do too.

This makes Big Tech uniquely difficult for a new competitor to take on and compete with. In the 90s, we may have thought of the internet as a great level playing field, where companies unfettered by geography would be able to compete, but the reality in 2019 is that if you want to start a new social network, you need to do it with a 10 million tonne gorilla in the room calling the shots. In other words, the barriers to entry are already incredibly high.

And this is why Article 13 makes things worse. It is widely thought that the only reasonable way of enforcing the new rules would be for platforms to effectively pre-moderate content to verify that nothing is being uploaded infringes copyright.

Technology to do this isn’t unheard of, as evidenced by YouTube’s automatic flagging of copyrighted footage in uploaded videos. But the resources to do it are significant and only really achievable by corporations that are already enormous. Crucially, it means that any competing social network will have to have built out functionality to perform similar checks – or risk being held at the mercy of the rights-holders. The new directive does have some exceptions for smaller companies – but the bar is set so low that if a new company is growing, the new copyright rules will make for a significant additional barrier to entry, long before the new company is in a position to challenge Facebook or YouTube.

So this is bad. Not just for memes, but ultimately, for us too. If we want Big Tech to stay accountable and behave responsibly, it needs to feel the heat of competition. The only way we’ll stop Facebook messing with our data, persuade YouTube not to radicalize people with its algorithm, or persuade Twitter to get rid of the Nazis, is if they feel as though if they don’t do anything, we consumers will click elsewhere – and Article 13 makes that harder.

James O’Malley is a freelance writer on technology and politics, and tweets as @Psythor