How Season on PS5 is taking in-game photography back to the future

Inside the making of Season's timeless photographic world

How can a camera change the way you see the world? This is the foundational question of photography, but also an increasing number of photo-centric games, including the much-anticipated PS5 and PC road trip adventure Season.

Season is part of a recent wave of games that make photography their cornerstone, rather than a tacked-on bonus mode. Some, such as Umurangi Generation, present the past-time as an urban artform, a tool to reclaim space through documentation. Others, like the classic Japanese horror game Fatal Frame, use the camera as a weapon, one capable of dispelling demonic presences.

But as members of the Season development team told us in an exclusive interview, their game is different. It's a quieter, more contemplative title that rewards careful observation. And its virtual camera, rooted in the meditative charms of film photography, is designed to foster an intimacy between the player and environment.

- These are the best PS5 games you can play right now

An analogue approach

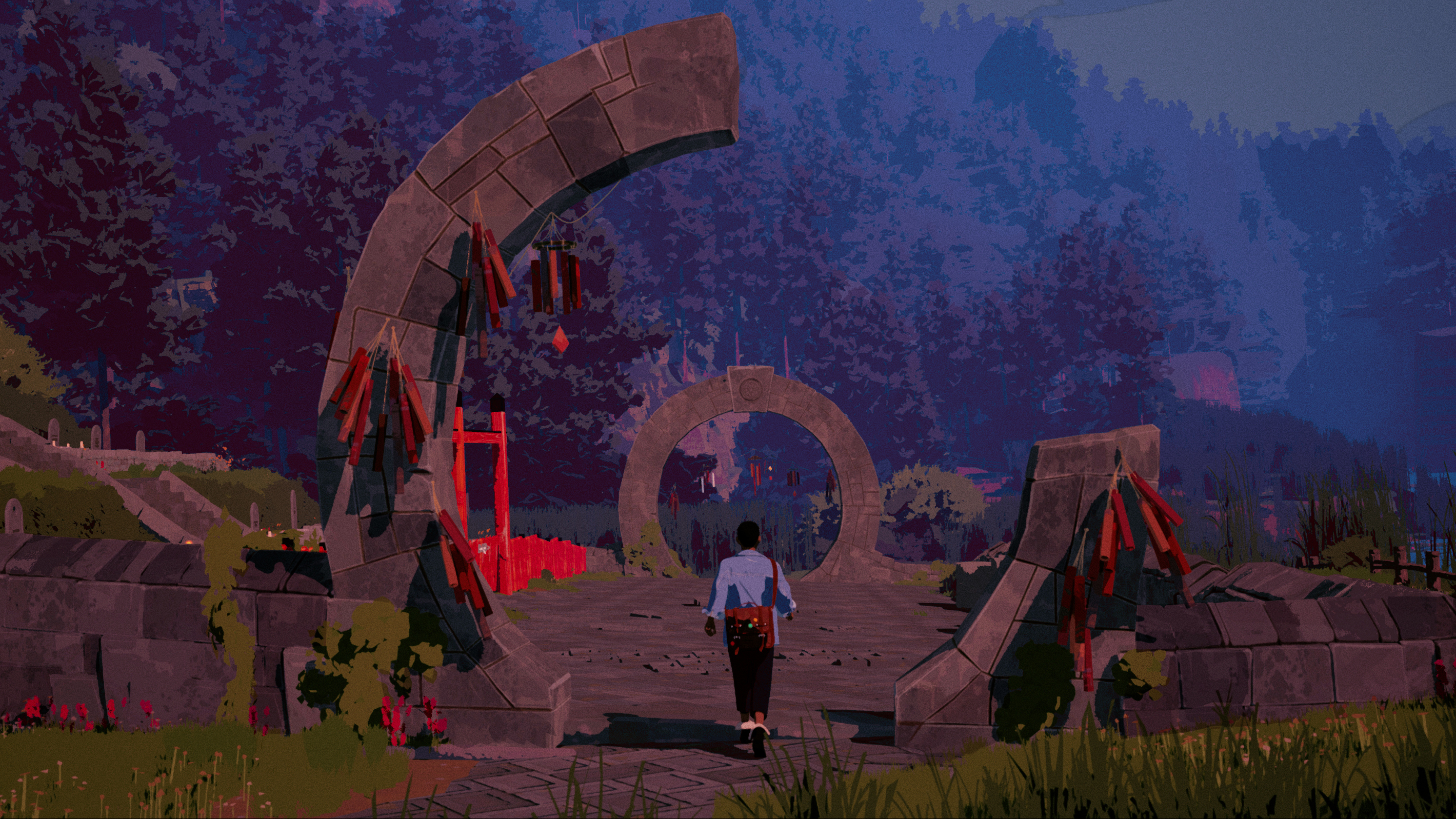

In Season's reveal trailer, we see a young protagonist cycling around a beautiful Studio Ghibli-esque world. “Our grandparents lived for a thousand years, and our parents had a century to themselves,” she says wistfully. “But us, we have one season.”

The world, as she knows it, is on the verge of collapse, and in order to make the very most of its last days, she sets off on a bike with the goal of recording its beauty. We catch a glimpse of a sketchbook filled with drawings of a ruinous monument, a tape recorder capturing the delicate sound of a dragonfly’s wings, and, most importantly, a camera directed at a bright-eyed primate.

“Everything in the game is about what photography is about,'' says creative director and writer on Season, Kevin Sullivan. “What it means to take a photo, what it says about the photographer, the fact that we can freeze time into images, these incomplete glimpses of the past. It’s so much in line with the themes we’re trying to show the player,” he adds.

Season, developed by Montreal-based studio Scavengers, has been worked on in one capacity or another since 2016, when it was just an idea of Sullivan’s inspired by his travels in south-east Asia. Before anything had even been programmed, he created video essays for the team, and even a functional board game to demonstrate how it might work in practice.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Now that the game’s production is in full swing, its form is a little clearer. There’s a world to explore filled with people to talk to, and of course, a bicycle to get around. At various points you’ll be able to pull out your camera to document your surroundings – animals, certainly, and panoramic vistas, but architecture and graffiti, all of which impart something special about the place before the “mysterious cataclysm washes everything away.”

Everything in the game is about what photography is about. What it means to take a photo, what it says about the photographer, the fact that we can freeze time into images, these incomplete glimpses of the past.

Kevin Sullivan, Scavengers Studio

In fact, the photography in Season has changed a great deal since its initial 2020 trailer. Camera aficionados may spot a machine that resembles a retro Bolex-style video camera (above), but this has morphed into a more straightforward film camera, says Stephen Tucker, senior VFX artist.

What hasn’t changed, he explains, is an emphasis on “older forms” of documentation. A keen photographer, he mentions his own Polaroid camera, the pleasing artifacts that emerge from using vintage film with an analogue camera and the relative “lack of control” if offers. “You won’t have a zoom range from 10mm to 300mm or something,” he continues. “You're going to have to roughly stand in the place that you need to stand in to take the photo that you want.” The aim ultimately, he says, is to create a device that feels “textural.”

Depth of field

Tucker isn’t the only photography enthusiast on the Season development team. Sullivan’s father was an aerial photographer, which meant his family’s basement was essentially a gigantic dark room. Then, at college, he started to get interested in the processing of analogue film while working on friends’ Super 16mm and 35mm movie projects.

There’s also Irwin Chiu Hau, 3D programmer on Season, who once worked as a professional photographer at weddings. He has his own collection of DSLRs and now takes landscape and macro photography for pleasure. The latter, essentially extreme close-up photography, feeds directly into Season. “There's a lot of little things in the world to shoot," Chiu Hau says tantalizingly.

But outside of real-world devices, earlier video games have helped shape Season’s in-game camera.

Tucker references the 1980s disposable camera used in the first-person drama 2016 Firewatch. In that game you get to snap the beautiful Wyoming forest and mountains, coated, at various points, in radiant orange sun. Another is 2017’s first-person adventure What Remains of Edith Finch?, which gives players an old-school camera for the duration of a rainy hunting trip. “I love the feel of the cameras in both of those games,” says Tucker.

Firewatch and What Remains of Edith Finch? arrived before video game photography as an in-game mechanic became really popular. More recently, Sludge Life and the award-winning Umurangi Generation have cast players as photographers in distinct cyberpunk futures. And just a few months ago, cult classic Pokémon Snap made its long-awaited return for players excited to pap their favorite made-up critters.

There are also two titles on the horizon which promise to add their own spin to the burgeoning micro-genre. Toem is a cute-looking adventure featuring anthropomorphic characters, while Martha Is Dead (above) takes the camera into altogether spookier territory with its 1940s Italian horror story.

Photography as a mechanic is seemingly in rude health, but none of these games quite offer the stirring, melancholic beauty of Season – the sense that the present is slipping through our fingers and must be commemorated in some way.

A change in focus

Still, regardless of tone and mood, what each of these games offer is a way of interacting with the world that doesn’t involve blowing it or its inhabitants up.

The camera can be a useful way of structuring gaze – of giving the simple act of looking a mechanical dimension for players who are keen to always do something.

Perhaps most importantly, it’s an action that’s intuitive for most people thanks to the extent to which smartphones have popularized the pastime. Everyone knows what to do, in other words. “The moment you take a camera out, you start to compose,” says Chiu Hau, “you start to frame the subject.”

While photography is increasingly folded into the gameplay of indie titles, for many blockbusters it exists as a discrete 'photo mode', separate to the game itself. All the player needs to do is pause the action at a particularly captivating moment and begin composing their shot.

In popular, eye-catching action titles such as Horizon Zero Dawn, God of War, and The Last of Us Part II, there’s almost an entire post-production suite folded into their photo modes, from lighting, focus, to field of view. Often, there are options to change the environment, including the time of day, weather, and even actual props in the shot.

While these tools are newly flexible, they’re part of a tradition that's nearly as old as gaming itself – that of so-called 'screenshotting', the forebear of modern video game photography.

Virtual tourism

Throughout the pandemic, Tucker says he’s been enjoying blockbuster video games as a means of vicarious travel, photographing his way through their stories and worlds as if he were on one of his own adventure holidays.

The lush vegetation and striking ruinous environments of The Last of Us Part II have offered a worthy subject, so much so that he's started printing out in-game photos using the Instax Mini Link.

For Sullivan, Season itself has manifested in the real world during the difficult past eighteen months. “I’ve been bike-riding around Montreal and taking pictures in an effort to try and learn more about it,” he says. “I feel like there’s an odd back and forth between the things we do influencing the game and feeling influenced by the game itself – just in certain pursuits and paying attention. Season feels like it’s bled into my actual life more than I’d anticipated it would when I started.”

Sullivan’s own experiences are precisely what’s appealing about Season and its in-game photography. Players looking for all of the bells and whistles of 'photo modes' may end up disappointed, and will those hoping for all the controls of a modern DSLR.

But those keen to experience the emotional essence of photography – specifically, the simplicity and immediacy of an analogue camera format – should be well served. By giving players a tool of the past, Season may provoke an entirely new perspective on the world.

Lewis Gordon is a Glasgow-based journalist who writes about culture, gaming and technology. He has previously written for Vice, Frieze, Art Reviews, the Verge and Wired. You can follow him on Twitter.