A formidable new rival is set to hit Intel and AMD where it hertz

Following AWS steps, Google is expected to launch new server CPUs within years

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

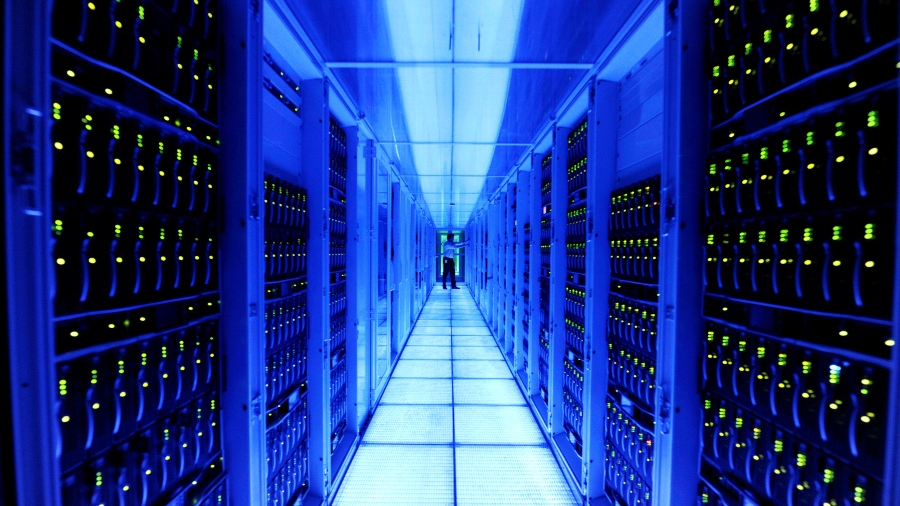

Google is expected to launch its own new server chips in a move that could have a huge long-term impact on Intel, AMD and other independent Arm-based chip manufacturers that rely on hyperscalers (the businesses that house cloud storage, web hosting, VPN and even Netflix) for revenue and growth.

According to a report published by The Information, within the next few years, Google is aiming to launch a rival to AWS’s Graviton server processor that has proven to be a roaring success for the world’s largest hyperscaler.

Sources claim the company Google has not one, but two server designs in place, running concurrently with ‘Cypress’, a fully custom design from Google Israel, pitched as Plan A and ‘Maple’, based on a design from Marvell Technology. The involvement of the latter is particularly interesting as Marvell stopped working on server CPUs in 2020, when it canned its Cavium-acquired ThunderX family - and one has to wonder whether Google’s Plan B would be based on the now-canceled ThunderX4.

Experienced heads

Google has almost a decade’s worth of experience with processors. Its latest, the G2, was announced in July 2022, making its full debut in the company’s flagship smartphones, the Pixel 7 and the Pixel 7 Pro. Before that, Google worked on so-called Tensor Processing Units (TPU), AI-specific accelerators that use ASICs (application-specific integrated circuit) for neural network machine learning.

So it seems that Google trying its hand at something bigger was just a matter of when, rather than if. Designing one’s own custom processor goes beyond mere cost savings as it allows Google’s engineers to bake in proprietary technology that cannot be found in off-the-shelf products from Intel and AMD. Tuning it to the extreme - something that can be achieved using Arm’s platform - will translate into faster time-to-market and energy saving.

In conversation with TechRadar Pro in 2022, AWS HPC specialist Brendan Bouffler explained that the Graviton series has given the company far greater freedom to optimize its operations, something Intel and AMD simply cannot provide.

“Graviton3 is optimized up the wazoo for our data centers, because we’re the only customer for these things. We know what our conditions are, whereas other manufacturers have to support the most weird and unusual data center configurations.”

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

What now for Epyc and Xeon?

Intel and AMD have known for more than a decade that this is the trajectory the industry was taking. After all, the world of high performance computing is a small, incestuous one with many veterans swapping roles: for example, Google’s VP of Engineering for server chip design is Intel’s CPU design veteran Uri Frank.

Both Intel and AMD have made acquisitions over the years that should help them weather the ongoing paradigm shift.

AMD acquired ATI back in 2006 as the catalyst behind its dream of an APU (Application Processing Unit) followed by the $35 billion Xilinx purchase in 2020 and Pensando in 2022. Intel on the other hand has a FPGA business from its 2016 acquisition of Altera, and has for nearly three decades dabbled into graphics and GPGPU (i740 all the way to Arc, Xeon Phi, Larrabee).

The world of data centers is moving away from being x86 centric to one where open platforms (like OCP) dictate where specialized heterogeneous processing units (DPU, GPGPU, CPU, NPU) co-exist.

We know that other hyperscalers, Tencent and Alibaba for example, have aggressively expanded their processing units plans, and we recently posited that Apple may do the same to augment Siri capabilities with ChatGPT-esque features. An S1 server chip based on the M1 architecture is not out of order. Facebook is also expected to have its own custom chips and the last of the big global hyperscalers - Microsoft - is already well versed in microprocessor design, with the Microsoft SQ2 (in the Surface Pro X).

- These are the best cloud hosting providers around today

Désiré has been musing and writing about technology during a career spanning four decades. He dabbled in website builders and web hosting when DHTML and frames were in vogue and started narrating about the impact of technology on society just before the start of the Y2K hysteria at the turn of the last millennium.