Early Verdict

While this might be wonderful for localised AI development, using it for anything else might be challenging. And, should the AI wind direction change, it might find itself largely redundant. However, Asus did an excellent job of engineering on the GX10.

Pros

- +

Unprecedented AI power

- +

128GB of LPDDR5x RAM

- +

200Gbps interconnect and 10GbE LAN

Cons

- -

No USB Type-A or USB4 ports

- -

Only a single 2242 M.2 slot for internal storage

- -

Other than storage, it's not internally upgradable

Why you can trust TechRadar

Rather than a review, this is a ‘hands-on’ in which I’ve explored what the Asus Ascent GX10 offers, providing information that might be critical to those considering purchasing one.

The first important piece of information about this hardware is that this isn’t a PC, or rather, it's not an Intel, AMD or X86-compliant platform that can run Windows.

It’s built around ARM technology, much like modern phones and tablets, although its ARM technology has been scaled up to work with massively powerful Nvidia Blackwell technology that is capable of 1 petaFLOP of AI performance using FP4.

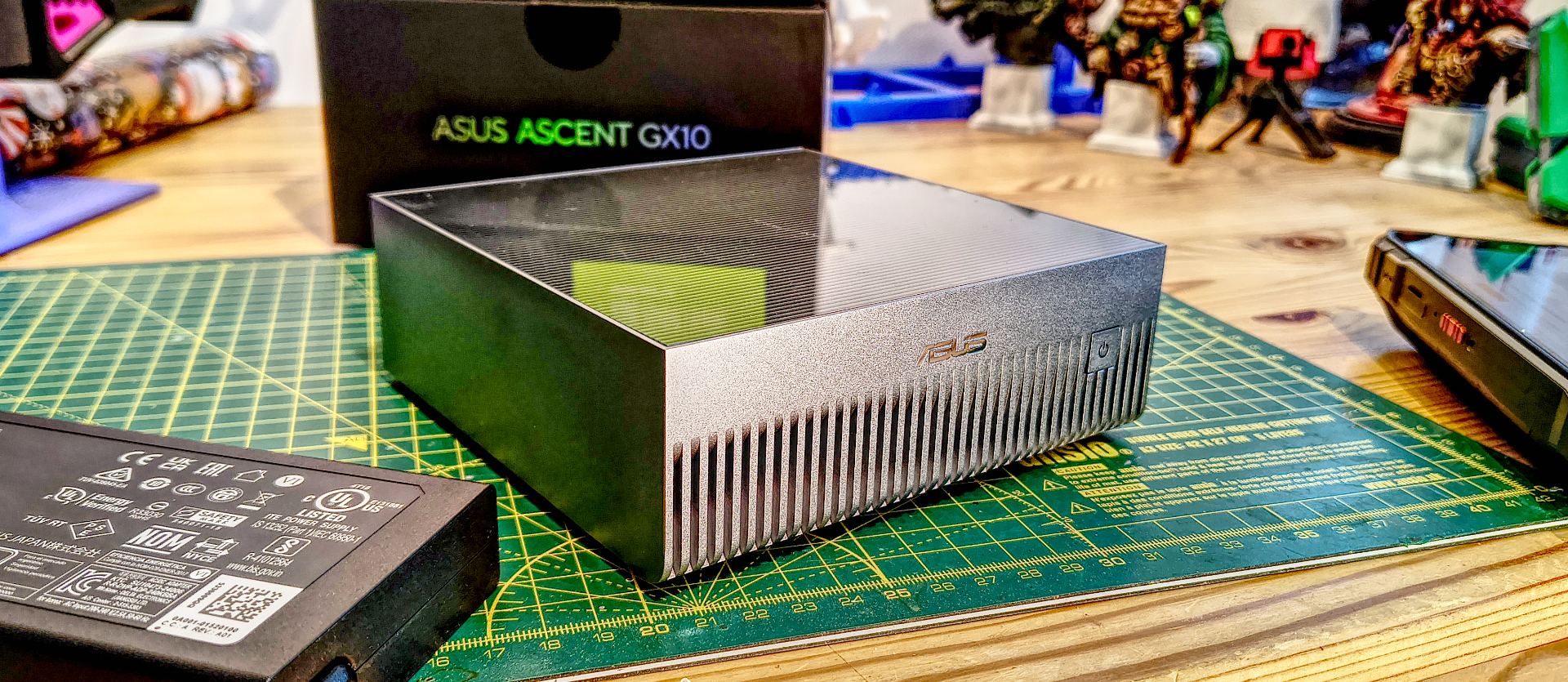

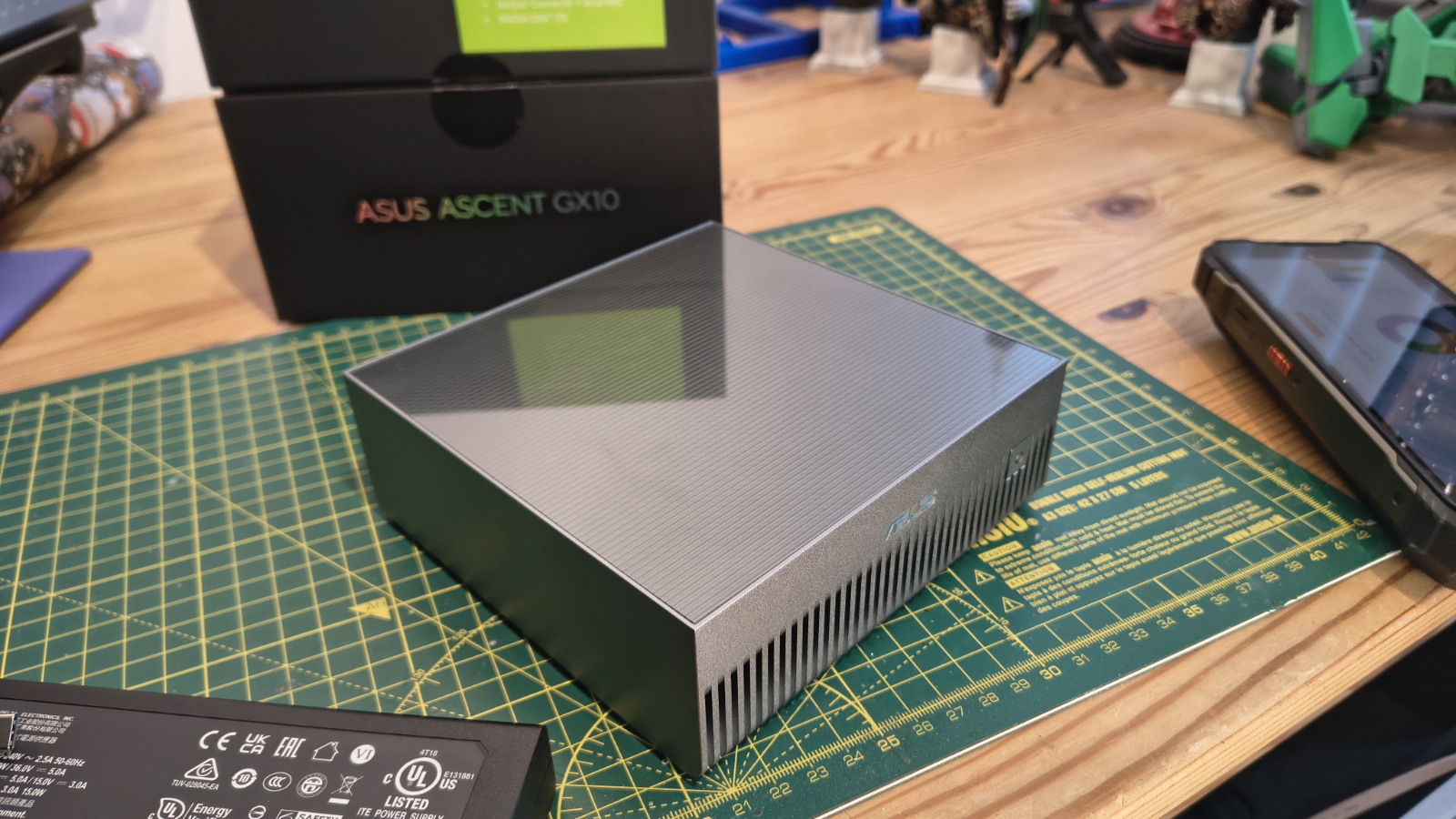

This has all been shoehorned into a gorgeously engineered 150mm-square, 51mm-high form factor that resembles an oversized NUC.

The system can be used directly by attaching a mouse, keyboard, and screen, but it’s also intended to be used in a headless mode from another system, which might explain why it comes with relatively modest onboard storage.

What this system doesn’t allow for is much expansion, at least internally. The inclusion of a special networking connection, the Nvidia ConnectX-7 port, does allow another Ascent GX10 node to be stacked on top, doubling the amount of processing power and the price.

The platform that runs the integrated AI software stack is Ubuntu Linux, so familiarity with that might be useful for those wanting to work directly on it.

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

As anyone working in AI can already attest, nothing to do with this type of development is cheap, and the Asus Ascent GX10 is more than $3000 for a single node.

But given the expertise needed to use this hardware and the associated developer costs, this AI-focused hardware might be the least expensive part of any project. And, with memory costs rising dramatically, a system with 128GB of LPDDR5X onboard it might be significantly more expensive by the end of 2026 than it is at the start of it.

Asus Ascent GX10: Price and availability

- How much does it cost? From $3090, £2800

- When is it out? Available now

- Where can you get it? From online retailers.

The ASUS Ascent GX10 isn’t available directly from Asus, but it's easy to find at many online retailers, including Amazon.

For US readers, the price on Amazon.com is $3099.99 for the 1TB storage SKU (GX10-GG0015BN), and $4,149.99 for the 4TB storage model (GX10-GG0016BN).

Given that a 4TB Gen 5 SSD is about $500, that is a remarkable price hike for the extra storage capacity.

For UK readers, on Amazon.co.uk the 1TB model price is £3769, but I found it via online retailer SCAN for a more palatable £2799.98. SCAN also carries a 2TB option for $3199.99 and the 4TB model for £3638.99.

The important details of this platform are that the hardware inside the GX10 isn’t exclusive to Asus, as Nvidia GPUs are (in theory) available across a number of brands, and Nvidia has its own model.

The Nvidia DGX Spark Personal AI Supercomputer, as the originator modestly calls it, costs £3699.98 in the UK, for a system with 128GB of RAM and 4TB of storage.

Acer offers the Veriton AI GN100, which bears an uncanny visual resemblance to the Asus but comes with 4TB of storage, like the Nvidia option. This is £3999.99 direct from Acer in the UK, but only $2999.99 from Acer in the US.

Another choice is the Gigabyte AI TOP ATOM Desktop Supercomputer, a 4TB storage model that sells for £3479.99 from SCAN in the UK, and can be found on Amazon.com for $3999.

And the final model with the same spec as most is the MSI EdgeXpert Desktop AI Supercomputer, selling for £3,598.99 from SCAN in the UK, and $3999 on Amazon.com for US customers.

Overall, the prices of all these products are roughly in the same ballpark, but the Asus in its 1TB configuration is one of the cheaper choices, especially for those in Europe.

Asus Ascent GX10: Specs

Item | Spec |

|---|---|

CPU: | ARM v9.2-A CPU (GB10) (20 ARM cores, 10 Cortex-X925, 10 Corex-A725) |

GPU: | NVIDIA Blackwell GPU (GB10, integrated) |

RAM: | 128 GB LPDDR5x, unified system memory |

Storage: | 1TB M.2 NVMe PCIe 4.0 SSD storage |

Expansion: | N/A |

Ports: | 3x USB 3.2 Gen 2x2 Type-C, 20Gbps, alternate mode (DisplayPort 2.1) 1x USB 3.2 Gen 2x2 Type-C,with PD in(180W EPR PD3.1 SPEC) 1x HDMI 2.1 1x NVIDIA ConnectX-7 SmartNIC |

Networking: | 10GbE LAN, AW-EM637 Wi-Fi 7 (Gig+) , Bluetooth 5.4 |

OS: | Nvidia DGX OS (Ubuntu Linux) |

PSU: | 48V 5A 240W |

Dimensions: | 150 x 150 x 51 mm (5.91 x 5.91 x 2.01 inch) |

Weight: | 1.48kg |

Asus Ascent GX10: Design

- Uber NUC

- Connect-7 scalability

- Limited internal access

While the GX10 looks like an oversized NUC mini PC, at 1.48kg it's heavier than any I’ve previously encountered. And that doesn’t include the substantial 240W PSU.

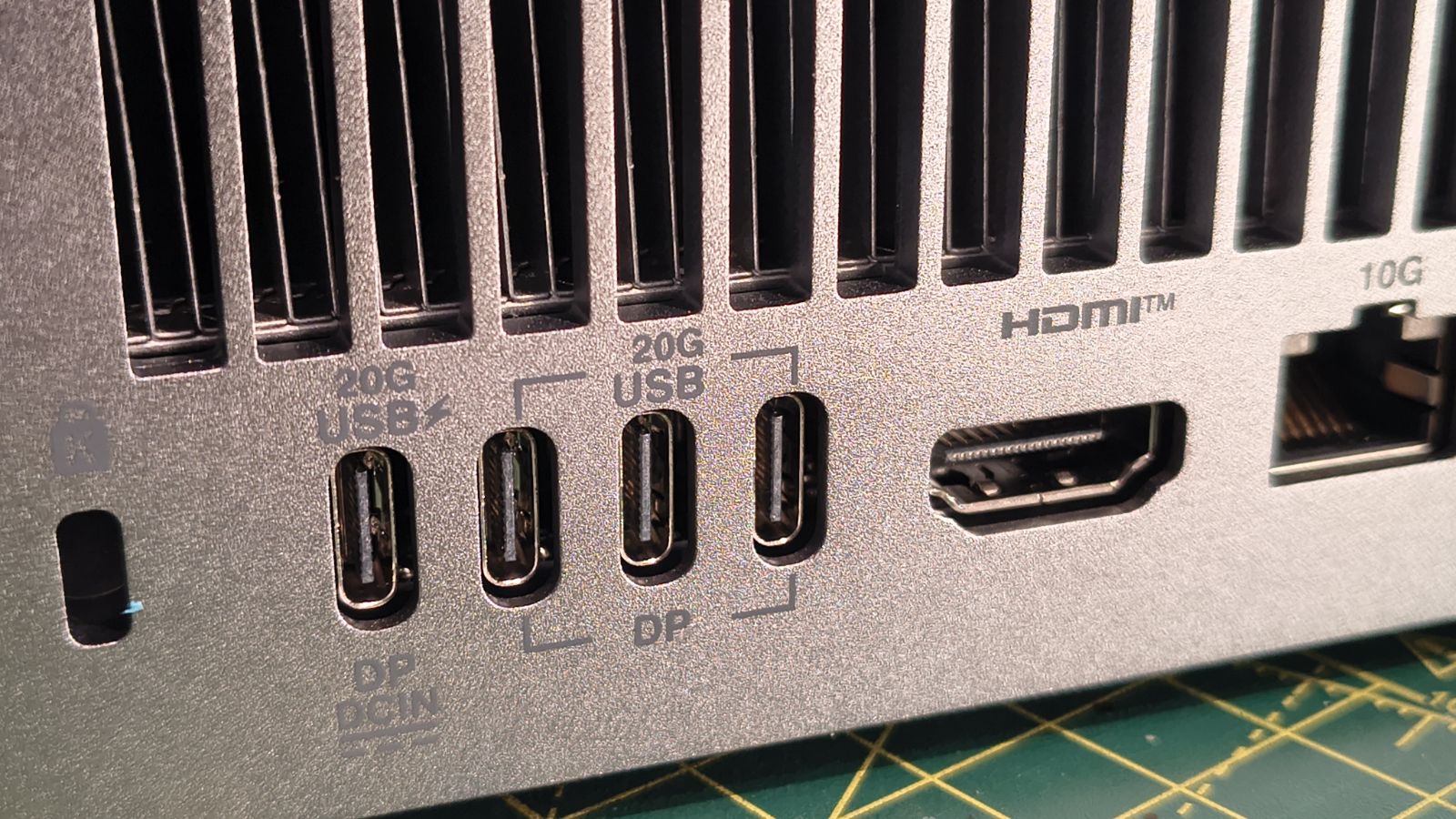

The front is an elegant grill with only the power button for company, and all the ports are on the rear. These include four USB-C ports, one of which is required for the PSU to connect, a single 10GbE LAN port and a single HDMI 2.1 video out.

You can connect more than one monitor by using the USB 3.2 Gen 2x2 ports in DP Alt mode, if you have the adapters to convert those into DisplayPort.

What seems mildly odd is that Asus went with three USB 3.2 Gen 2x2, a standard that was an effective dead end in USB development, and not USB4. And, there are no Type-A USB ports at all, forcing the buyer to use an adapter or hub to attach a mouse and keyboard to this system.

As mice and keyboards are still mostly USB-A, that’s slightly irritating.

But what makes this system truly interesting is the inclusion of a ConnectX-7 Smart NIC alongside the more conventional 10GbE Ethernet port.

The best the 10GbE LAN port can offer is a data transfer of around 840MB/s, which is technically slower than the USB ports, even if it's quick by networking technology.

The ConnectX-7 port is a technology developed by Mellanox Technologies Ltd, an Israeli-American multinational supplier of computer networking products based on InfiniBand and Ethernet technology that was acquired by Nvidia in 2019.

In this context, ConnectX-7 provides a means to link a second GX10 directly over a 200 Gbit/s (25 GB/s) InfiniBand network, enabling performance scaling across the two systems.

There are certainly parallels with this type of technology to the time when Nvidia enabled two GPUs to work in unison using a dedicated interconnect, but the ConnectX-7 interface is a much more sophisticated option where both processing and memory can be used in collective exercise, enabling the handling of large-scale models with over 400 billion parameters. That's double the 200 billion that a single unit can cope with.

Mellanox does make ConnectX switches, but I’m not sure if it is possible to connect more than two GX10 via one of those. Being realistic, each system is still only capable of 200 Gbit/s communication, so adding additional nodes beyond two might offer diminishing returns. But this technology is utilised in switched fabrics for enterprise data centres and high-performance computing, and in these scenarios, the Mellanox Quantum family of InfiniBand switches supports up to 40 ports running at HDR 200 Gbit/s.

It may be that products like the GX10 will be the vanguard for the wider use and application of ConnectX technology, and a blueprint for easily expandable clusters.

However, the last aspect I looked at on the GX10 was a disappointment, and it was the only nod to upgradability that this system has, beyond adding a second machine.

On the underside of the GX10 is a small panel that can be removed to provide access to the one M.2 NVMe drive that this system supports.

In our review, the hardware was occupied by a single 2242 M.2 PCIe 4.0 1TB drive, although you can also get this system with 4TB. The fact that there wasn’t room for a 2280 drive is a shock, because that effectively limits the maximum internal storage to 4TB.

But conversely, the only other of these types of systems I’ve seen, the Acer GN100 AI Mini Workstation, has no access to the internal storage at all. So perhaps Asus Ascent GX10 owners should be thankful for small mercies.

Asus Ascent GX10: Features

- ARM 20-core CPU

- Grace Blackwell GB10

- AI platforms compared

The Nvidia GB10 Grace Blackwell Superchip represents a significant leap in AI hardware, emerging from a collaborative effort between Nvidia and ARM. Its origins lie in the growing demand for specialised computing platforms capable of supporting the rapid development and deployment of artificial intelligence models. Unlike traditional x86-based systems, the GB10 is built around ARM v9.2-A architecture, featuring a combination of 20 ARM cores—specifically, 10 Cortex-X925 and 10 Cortex-A725 cores. This design choice reflects a broader industry trend towards ARM-based solutions, which offer improved efficiency and scalability for AI workloads.

The GB10’s capabilities are nothing short of remarkable. It integrates a powerful Nvidia Blackwell GPU paired with the ARM CPU, delivering up to a petaFLOP of AI performance using FP4 precision. This level of computational power is particularly suited to the training and inference of large language models (LLMs) and diffusion models, which underpin much of today’s generative AI. The system is further enhanced by 128GB of unified LPDDR5x memory, ensuring that even the most demanding AI tasks can be handled efficiently.

The GB10’s operating environment is based on Ubuntu Linux, specifically tailored with NVIDIA’s DGX OS, making it an ideal platform for developers familiar with open-source AI tools and workflows.

There is an exceptionally fine irony to this OS choice, since Nvidia’s hardly been a friend to Linux over the past three decades, and has actively obstructed its attempts to compete more widely with Microsoft Windows. If anyone doubts my opinion on the relationship between Linux and Nvidia, then search for “Linus Torvalds” and “Nvidia”. Recently, Linus has warmed to the company, but much less to Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang. And, he’s not a fan of the AI industry, which he described as "90% marketing and 10% reality".

Looking to the future, the evolution of the GB10 and similar superchips will likely be shaped by the ongoing arms race in AI hardware. As models grow ever larger and more complex, the need for even greater memory bandwidth, faster interconnects, and more efficient processing architectures will drive innovation. The modularity offered by technologies like ConnectX-7 hints at a future where AI systems can be scaled seamlessly by linking multiple nodes, enabling the handling of models with hundreds of billions of parameters.

In terms of raw AI performance, the GB10 delivers up to 1 petaFLOP at FP4 precision, which is heavily optimised for quantised AI workloads. While this is less than the multi-petaFLOP performance of NVIDIA’s flagship data centre chips (such as the Blackwell B200 or GB200), the GB10’s power efficiency is a standout. It operates at around 140W TDP, far lower than the 250W or more seen in GPUs like the RTX 5070, yet offers vastly more memory (128GB vs 12GB on the 5070). This makes the GB10 especially suitable for developers and researchers who need to work with large models locally, without the need for a full server rack.

While there are some other players hidden in the shadows, mostly Chinese, the key AI players are Nvidia, AMD, Google and Apple.

NVIDIA has the Blackwell B200/GB200 products for datacenter flagships, offering up to 20 petaFLOPS of sparse FP4 compute and massive HBM3e memory bandwidth. These are massively expensive enterprise products, and the GB10, by contrast, is a scaled-down, more accessible version for desktop and edge use, trading some peak performance for efficiency and compactness.

AMD's line of AI accelerators is the Instinct MI300/MI350, these are competitive in terms of raw compute and memory bandwidth, with the MI350X offering up to 288GB HBM3e and strong FP4/FP6 performance. But these don’t offer the same level of flexibility as the GB10, even if they’re better suited to interference tasks. And, the same can be said for Google TPU v6/v7, a technology that is highly efficient for large-scale inference and is optimised for Google’s own cloud and AI services.

Whereas Apple M3/M4/M5 and Edge AI Chips are optimised for on-device AI in consumer products, with impressive efficiency and integrated neural engines. However, these chips are not designed for large-scale model training or inference, and their memory and compute capabilities are far below what the GB10 offers for professional AI development.

The NVIDIA GB10 Grace Blackwell Superchip stands out as a bridge between consumer AI hardware and data centre accelerators. It offers a unique blend of high memory capacity, power efficiency, and local accessibility, making it ideal for developers and researchers who need serious AI capability without the scale or cost of a full server. While it cannot match the absolute peak performance of the largest data centre chips, its unified memory, advanced interconnects, and software support make it a compelling choice for cutting-edge AI work at the desktop.

However, that statement does assume that current AI is a path work taking.

Asus Ascent GX10: AI Reality Check

Looking at the specifications of the Asus Ascent GX10, it's easy to be impressed by how much computing power Asus, with the help of Nvidia, has managed to squeeze into a tiny computer, and its ability to scale.

However, there are three practical little pigs living in this AI straw house, and in this story, I’m the wolf.

Those researching AI might think I’m referring to the three AI issues that confront all public implementations. Those being algorithmic bias, lack of transparency (aka explainability), and the significant ethical/societal risks associated with the spread of misinformation. But I’m not, because these are potentially fixable to a degree.

Instead, I’m talking about the three unfixable issues with current models

Almost every AI platform is based on a concept called the Deep Neural Net, and under that are two approaches that are generally classified as LLM (Large Language Models) and Diffusion models, which are the ones that can generate images and video.

What both these sides of the Deep Neural Net coin show is a pattern-matching approach to problems, like the computer is playing a complex version of the children’s card game Snap. The results are coloured by the scale of the data and how quickly the routines and hardware platforms find the patterns.

Before IBM made computers, they sold card files, with the concept that it was quicker to navigate the cards to the information you wanted.

It’s a generalisation, but these models are purely more sophisticated versions of that, because if the pattern they’re looking for doesn’t exist in the data, then the routine can’t inspirationally create it.

To make the results seem less random, model designers have tried to specialise their AI constructs to focus on narrower criteria, but the Nirvana of AGI (Artificial General Intelligence) is that the AI should be generally applicable to almost any problem.

How this issue manifests in AI responses is that when confronted with a pattern that the routine can’t match accurately, it just offers up the partial matches it found that may or may not be related at all.

These ‘hallucinations’, as they’re often called, are a choice the model makers have between the AI admitting it has no idea what the answer is, and delivering a response that’s got a remarkably low possibility of being correct. Given that AI companies don’t like the idea of their models admitting they haven’t a clue what the answer is, hallucinations are deemed preferable.

Perhaps some of the problem here is not AI, but that users aren’t trained to check what the AI is producing, which isn’t entirely spurious.

The next issue is the classic ‘prompt injection’ issue, where you ask a question, and then, often based on the response, you realise you asked the wrong one, and then proceed in an entirely different direction. The AI doesn’t recognise this pivot and tries to apply its previous pattern constructions to the new problem, and becomes entirely confused.

And the final piglet, where current AI entirely falls down, might be classed as original thinking, where what the user wants is a new approach to a problem that hasn’t been documented before. What has defined humans as being especially impressive thinkers is their ability to abstract, and that is something that current AI doesn’t do, even modestly.

While prompt injection can probably be solved, the other two issues regarding generalisation and abstraction are unlikely to be fixed by the Deep Neural Net, these need a radically new approach, and ironically, not one that AI is likely to come up with.

Some of you reading this will be wondering why I’ve inserted this information into this product reveal, but the whole purpose of the Asus Ascent GX10 is to facilitate the design and testing of LLMs and Diffusion models, and at this time, these have significant limitations.

But critically, the development of the whole Deep Neural Net direction doesn’t appear to have resolution to some of the more problematic issues, which suggests it might ultimately be a dead end.

It might turn out to be useful for lots of problems, but it's not the AI we’re looking for, and the likelihood of it evolving into that true artificial intelligence is extremely low.

This is especially relevant to the Asus Ascent GX10, since it doesn’t have a practical purpose beyond the creation of models, as it’s not a PC.

These aren’t all the issues associated with AI, but they’re some of the ones that might directly impact those buying the GX10, at some point or another.

Asus Ascent GX10: Early verdict

It’s exciting to see Asus make something this radical, showing that it truly believes in a post-Windows, post-PC future where hardware is purely specified for a specific task, and in the case of the Asus Ascent GX10, that’s AI model development.

I’ve already covered the caveats regarding that subject, so for the purpose of this conclusion, let's pretend that AI is the solid bet that some think, and not an underachieving dead end that others believe.

For corporations, the cost of this hardware won’t be an issue for their IT people to experience building AI models and evaluating their worth.

The beauty of a system like the GX10 is that it’s a finite cost, unlike buying access to an AI server centre cluster, which will be an ongoing cost, and likely to become more expensive if demand is high. While the data centre still might be needed for the biggest projects, or for deployment, the GX10 does provide a first rung for any proof of concept.

However, if the AI path is not the one that is ultimately taken, this machine becomes mostly a beautifully engineered paperweight.

For more compact computing, see our guide to the best mini PCs you can buy

Mark is an expert on 3D printers, drones and phones. He also covers storage, including SSDs, NAS drives and portable hard drives. He started writing in 1986 and has contributed to MicroMart, PC Format, 3D World, among others.

What is a hands on review?

Hands on reviews' are a journalist's first impressions of a piece of kit based on spending some time with it. It may be just a few moments, or a few hours. The important thing is we have been able to play with it ourselves and can give you some sense of what it's like to use, even if it's only an embryonic view. For more information, see TechRadar's Reviews Guarantee.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.