Why you can trust TechRadar

With this focus Nvidia's hoping that, unlike when the first DX10 cards came out, this top-end card will still be a worthy part when full DirectX 11 games hit the shelves with heavier and heavier reliance on tessellation.

We've already seen the DX11-lite titles such as STALKER: Call of Pripyat and DiRT 2, which bolted on some effects to buddy up with the launch window and possibly some shared budgets with AMD, but it's only really the likes of Metro 2033 that are developed with DX11 more in mind.

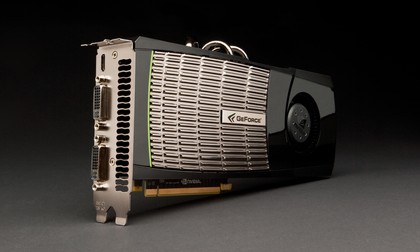

The GeForce GTX 480, representing the top-end of the Fermi spins, does hint at some trouble in the yields from Nvidia's 40nm wafers.

Problems with production?

The full GF100 chip sports 512 CUDA cores (previously known as stream processors, or shader units) across its 16 streaming multiprocessors (SMs). However, the GTX 480 is only sporting 480 of those CUDA cores, supporting the rumour that in order to improve the yields of the 40nm Fermi wafers Nvidia had to sacrifice some of the shader units.

As Tom Petersen, Nvidia's Technical Marketing Director, told us, "it's not the perfect [GF100] chip."

So it's wholly possible that yields of fully functional chips, running all 512 cores, were so low as not to be commercially viable. Switching off 32 of these units is thought to have upped the number of usable chips from each of its 40nm wafers enough to make a commercially viable chip.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Of course, Nvidia doesn't agree this is what was responsible for the many delays to the launch of a Fermi-based card. Nvidia puts the blame for the delays down to DirectX 11 itself. The big, sexy buzzword surrounding Microsoft's latest graphics API is tessellation, and it's this feature Nvidia claims was responsible for the card's tardiness.

Nvidia sees tessellation as the great hope for PC gaming going forward and was so desperate to make sure it had the best architecture to take advantage of Microsoft's new API that it was willing to wait half a year before releasing a graphics card capable of using all that tessellated goodness.

While initially this seemed like a risky strategy, it looks like it could pay off well for the green side of the graphics divide

AMD made sure it had DX11 cards ready and waiting (though not necessarily on the shelves thanks to its own yield issues) for the launch of DX11, but in relative architectural terms Nvidia claims it only really pays lip-service to tessellation.

With the single tessellation unit of AMD's Cypress chips compared to the 16 tessellation units wrapped up in each of Fermi's SMs it's immediately obvious where Nvidia sees the future of PC graphics.

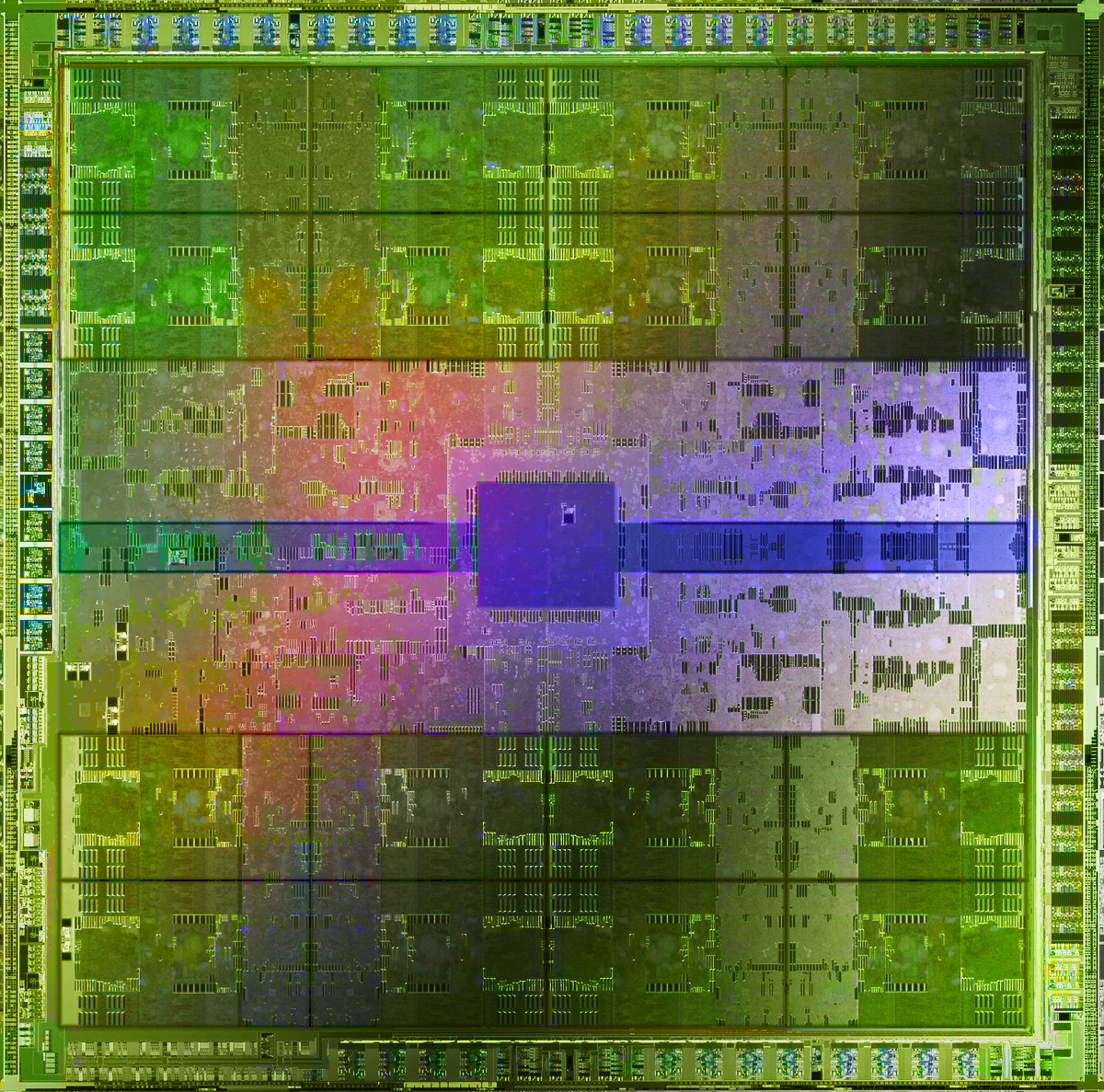

Despite the fact the GF100 GPU is a big, blazing hot, power-hungry beast of a chip, it is also rather neatly designed. In terms of layout it's very much like a traditional CPU, with independent sections all emptying into a shared Level 2 cache.

This means that it's designed from the ground up to be well versed in the sort of parallelism that Nvidia is aiming for from its CUDA-loving graphics cards.

This parallelism was initially taken as proof positive that Nvidia was abandoning its gaming roots, making more concessions architecturally to the sort of high performance computing (HPC) that gets used to solve advanced computing problems.

The GTX 480, for example, is the first GPU to be able to achieve simulation speeds of 1ms/day when plugged into the Folding@home network.

But speak with Nvidia's people and it becomes clear that this architecture is also perfect for taking advantage of today's demanding 3D graphics too. The full GTX 480 chip has sixteen separate stream microprocessors, each housing thirty of Nvidia's CUDA cores.

Each of these SMs can tackle a different instruction to the others, spitting the results out into the shared cache, before starting another independent instruction.

This means the GTX 480 is able to switch between computationally-heavy computing - like physics for example - to graphics far quicker than previous generations. Each of these SMs has its own tessellation unit too, so for particularly intensely tessellated scenes the chip is able to keep running other instructions at the same time.

AMD's solution outputs its data directly into the DRAM, compared with Nvidia's solution that keeps everything on the chip. This means the GTX 480 isn't overloading the valuable graphics memory quite as much.

Current page: Nvidia GeForce GTX 480: Specifications

Prev Page Nvidia GeForce GTX 480: Overview Next Page Nvidia GeForce GTX 480: Performance