Roguelikes: how Spelunky, Dark Souls and Isaac made death matter again

Exploring the genre that institutionalized perma-death

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Death should be permanent. When games emerged in the early eighties, they opted for a certain count of lives. Usually three, though in many cases, this could be increased to five, or seven, or nine. Mario plunged into bottomless pits, Sonic brushed against one too many spikes and we’d wait for a jingle to finish before being reborn on screen for another attempt. This is how life played out when we sat cross-legged in front of large televisions; impressionable minds seeing second chances.

Once that handful of lives was used up, we’d be offered the chance to continue. Jabbing the start button would track us back to the beginning of the level, a set-back, but revitalized with more life. There was always a lifeline, a safety net, if you will. We could play with abandon, attacking levels because we knew that should death take us, there would be another go around.

Coming back from the dead lingered as a central trope of gaming for many years. So many offered a counter along the edge of the screen, ticking off attempts in a steady stumble towards game over or eventual success. If it wasn’t life counts, this safety net could be seen in steady checkpoints, numerical passwords in the 16-bit era or later, as save files. We were lulled into a sense of security, knowing that no matter how fast we move or how ferociously we attack enemies, we could come back, utilising the same skillset as before. If you struggled to land a jump in Tomb Raider, it wasn’t a problem, Lara respawned a few paces away from the edge to try, try again.

Roguelikes offer us as humans a level of comfort once we’ve mastered the mechanics. Repetition is an important aspect of life giving us a chance to repeat actions in search of new outcomes or to prove our learning to ourselves. Certain combinations of items in these games often synergize differently with each other, urging us to try again. With randomization keeping things fresh, players can explore new ideas within the safety of repetitive parameters.

It didn’t take long for games to begin emulating life, offering just one attempt to reach a goal. Perhaps the most notable example of this is Spelunky.

Sure, while an intrepid explorer venturing into cave systems seeking elusive treasure wasn’t exactly groundbreaking, the mechanics were. Given just a whip, some bombs and a handful of ropes, the idea was to reach Olmec and relieve the God of their treasure. Exploration was integral, emphasizing the explorer archetype. Levels were laden with traps hiding inside walls to fire arrows and there are often blind drops, with spikes waiting at the bottom. The change here was that you only had one attempt, and should you die, it would be straight back to the beginning of the game, losing everything you collected along the way.

Safety nets now came as items; a parachute for those long drops or if you had collected enough money, the Ankh inside the hidden Black Market would save your life just once. Spelunky tested patience, forcing players to slow down, evaluate the layout of mines, ice caves and temples. From here, games were relying less on instinct and reaction and more on choice. Weighing up the pros and cons of venturing further to reach the crate that might hold the key to success. Roguelikes or Roguelites, as they were dubbed, suddenly moved from a more niche slice of games into the mainstream. Developers noted how Spelunky dealt with several mechanics, establishing them as tenets of the genre; death, knowledge and randomization.

Dungeon-crawling and risky brawling

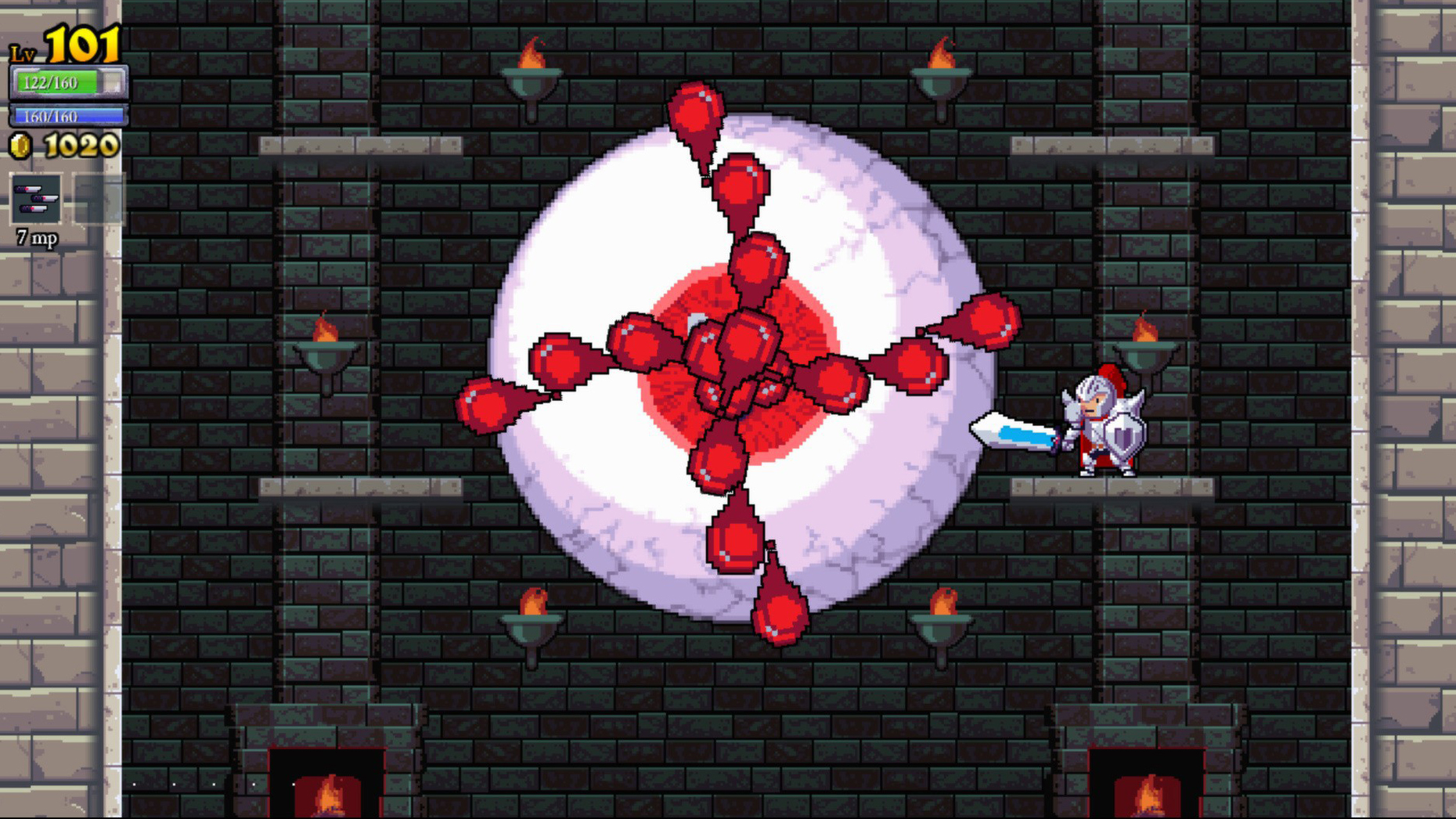

For a small handful of pioneering titles, death was now permanent ... for that iteration of your character at least. Life became precious and players became wary, knowing that each action could very well be their last. Rogue Legacy, The Binding of Isaac, even Dark Souls all consider the balance of risk and reward. Progression was now a gamble; do you take the new item, not knowing how it will affect your journey? Or do you leave it behind?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Of course, some players love the risk, not caring if they lose an hour of progress for the chance to see something new. Others play closer to caution, teasing outcomes with baby steps. Maybe the item will subvert death anyway? “Progression in any form is a primal desire in humans, and most Roguelikes are progression systems on steroids,” says Teddy Lee of Cellar Door Games, creator of Rogue Legacy.

Progression in any form is a primal desire in humans, and most Roguelikes are progression systems on steroids.

Teddy Lee

To progress in life, we make decisions and choices. Sometimes we turn down that new job because the change to life isn’t worth the chance. What if we had taken a stand against that bully when we were younger? Often games don’t offer this sense of decision making, at least not with such finality.

Away from TellTale adventures, these game-altering choices are less seen, action titles are often more linear, affording the player risk only in difficulty of set pieces or number of obstacles. The ability to save games on a whim can lead to reloading a file if we didn’t enjoy the outcome of a decision.

With Rogue games, that function is rarely an option. Take the item ‘Plan C’ in The Binding of Isaac, an active item used at will. It’s an innocuous looking red pill, whose name only vaguely hints at the outcome of its use. Upon using the item, the character will kill everything in sight, dealing out massive damage to even the hardiest of bosses, but the protagonist will also die. Plan C is an abortion drug in America, now you know. The player must then react and adapt, knowing that this item can only be used if they’ve picked up a way to resurrect after the act.

“The Roguelike genre is a lot like real life, sometimes crazy shit happens and you win the lotto, or sometimes you get your face torn off by that monkey from the Old Navy commercial,” Isaac creator Edmund McMillen expresses. “You are gambling with your life, basically.”

This idea grew over time and the gap between games and life shrunk, with developers not only intent on asking you to go all in on your character, but to also do so with those around you. Indie games were perhaps the first to implement the mechanic of ‘perma-death’, with larger studios following suit to bring it to audiences at large. Creators allowed for teammates or party members to improve over time, unlocking new skills, encouraging the player to rename them and form a bond. Faster Than Light, X-Com and Fire Emblem forced players to care for those around them, knowing that if a key member of the team died, there was no coming back. Our choices began to hold weight – do you send your ace pilot into the fight knowing if they die, your progress will take a step back as you train someone new?

While the indie scene often gives these new ideas because of the freedom within creation, the tropes eventually bleed through to triple-A titles. Minit designer Jan Nijman reflects on the indie scene for its freedom of mechanics: “Small teams are flexible. If you're a solo developer with loads of free time, you can make whatever you want. On the other hand, if you're responsible for 200+ employees and their mortgages, it's super dangerous to take risks”.

The theme of perma-death is perhaps best displayed in ‘triple-A’ titles such as Until Dawn, where you control a group of protagonists in a horror movie setting, trying to keep each of them alive. Once they die, there’s no reloading a save to try again as the game constantly backs up your progress, making the choice of exploring the sound outside the cabin all the more dangerous. Lending a new style of excitement and fear to proceedings. Death should be consequence, not inevitability.

Carrot and the stick

Venturing into the unknown allows for risk and reward gameplay, developers dangle opportunities like carrots on a stick. Consequence means a lot more in the Rogue genre because the decision can be catastrophic, do you take the money or see what’s behind the door? Opening a strange pod in F.T.L can unleash an alien who savages a member of the crew. Dealing with the devil in The Binding of Isaac directly asks the player to make a sacrifice for potential growth. If you play well over a floor of Isaac, not losing any integral red heart health, the devil will appear with a selection of items, most of which will increase damage or offer a lifeline upon death. To accept these, you must sacrifice your health. As Edmund McMillen notes, “the risk of a heart or two for higher damage is one you will always take, but devil items cost life and ask you whether or not give into temptation”.

It’s “only a heart or two”, but that damage buff might be key to winning.

There’s still a hint of the old way of life. Each death gives us time to reflect, we can analyse each choice we made along the way, using that information in the next attempt, or the next life. “In a good Roguelike, the players' eventual failure should always be a moment they can understand, learn from, and try again,” explains Rami Ismail, creator of Nuclear Throne. This is the central tenet for the genre. Knowledge comes from death and death is used as a tool. Sometimes a ‘run’ will inevitably end in failure, even sacrifice, as we seek out information or try new things. In Nuclear Throne, one of the weapons is a screwdriver, which if used on the right car opens a secret level. Use it on the wrong car, or even the wrong enemy and it will explode, ending your progress abruptly. Experimentation is key, death is inevitable and growing as a player through mortality is a must. Think of it as being born again, or as Edmund McMillen subtitled The Binding of Isaac HD release, Rebirth.

Three letters are sliding into our gaming lexicon more and more as the years pass but have been a focus for developers since the sprouting days of Acorn computers and Atari consoles. ‘RNG’ or ‘Random Number Generation’ is used in most games as the engine or AI produces random stats or timings to trigger enemies. Consider it like a dice-roll, determining and controlling the elements around the player.

This technique is used for creating ‘seeds’ which dictate the layout of a level or the placement of items. It’s in the RNG that Minecraft knows where to place biomes or Spelunky juggles the tile-based level design to create unique pitfalls and risks with each playthrough.

One game to implement the idea of handing down skills and knowledge, passing on traits and riches, is Rogue Legacy. Rather than asking us to choose a template character each time, the team utilise a lineage system. Starting a new ‘run’ meant receiving some of the money from a past life, along with any upgrades made to that character. “We had to upfront the player change as early as possible,” says creator Teddy Lee. “This led to classes, which led to sub-weapons, which eventually led to genetic traits and the lineage system.”

Learning the mechanics of a Rogue game subverts how we usually learn about games. We know Mario can run faster holding down the ‘B button’ furthering his jump, this is a skill given to us by developers, without which many levels would be impossible to finish. “I enjoy Roguelikes because they encourage players to learn the underlying systems as opposed to ‘routes’ of designer intentions,” explains Lee.

However, Lee doesn’t agree that sacrifice is needed within the genre to learn: “weeding out false paths is artificial complexity at its worst.”

Along with reinventing mortality and urging players to adapt to new design structure, players take another step closer to life with the random element of Roguelikes and lites. It’s not often that the words Rogue and procedural generation aren’t hand in hand, as teams endeavour to emulate the randomness of life within our games. This can come from items, where you’ll never know what lies inside a chest or, most notably, level generation. Videogames are often an escape from life, but Rogue games offer the risks of real life with little to lose. “Failure does not have any real-life results - beyond your run getting cut short,” notes Rami Ismail. This genre and its quirks offer players a new way of controlling the random things we meet in real life – danger, risk, choice – without the inherent idea of failing or regret.

Rogue reincarnation

I enjoy Roguelikes because they encourage players to learn the underlying systems as opposed to ‘routes’ of designer intentions.

Teddy Lee

Looking back to rebirth, there’s an air of Eastern religion about Roguelikes, each of these new playthroughs or ‘lives’ can be seen as a form of reincarnation. Buddhist teaching describes reincarnation as a process of being born over and again, improving upon previous incarnations in order to reach Nirvana, or enlightenment. This is the key similarity between the two; they each hold a certain goal in mind, though with games, it’s usually to reach the end credits or in some cases, the perfect run.

Oddly, for a game that kills its central character every 60 seconds, Minit’s designer Jan feels that the game isn’t about death, but rather life. “‘Minit has never been about the death part: It's a representation of leading a very rushed life while everybody else seems comfortable where they are, and the idea that you always need to be productive,” she explains. “Minit is about how that's not always the case, and how sometimes it's fine to just stop and look at the world, to explore, and to interact with the people around you.”

No other genre leans so closely to the real life we live away from our computers and consoles. As the genre grows and infiltrates so many titles, we as players are given the chance to make weighty choices that have a real sense of outcome.

Rogue games don’t offer only black and white decisions of choice like so many adventure games, there’s a kaleidoscope of shades built from random chance and risk. Some of those will take us down a dark road tinged with loss and grief and others will lead to enlightenment.

Daniel Lipscombe have worked as a freelance writer for around nine years, starting in video games before moving to literature for a time. During his time working with books, he also worked for Essex Book Festival, and spearheaded diversity in literature with a campaign covered by the BBC and national UK newspapers.