Why Google isn't evil

How Google.org is using its algorithms to save the world

If knowledge is power, the Google revolution has empowered us all. Never in human history have so many people had access to so much knowledge, made relevant and ordered to their needs.

And while critics may decry the company's privacy-invading omniscience, from Street View to Latitude (mobile phone software that tracks your friends' whereabouts), what's less publicised are its little-known humanitarian projects through its charitable arm, Google.org.

Call it goodwill or a fluffy PR tactic: either way, Google.org is sizing up its technologies for the world's pressing issues – by getting information quickly to disaster relief teams, finding new ways to save energy, and helping impoverished communities.

The organisation is also funding other charitable groups with $100million, and has pledged one per cent of Google's profits for philanthropic purposes.

Predicting outbreaks

Last April, swine flu took the world by surprise. After the 2003 Asian bird flu outbreak died down, public health experts suspected the next epidemic would come from Southeast Asia, where dingy slums and a moist climate breed germs. If any developing country was low on the World Health Organisation's list of candidates, it was Mexico.

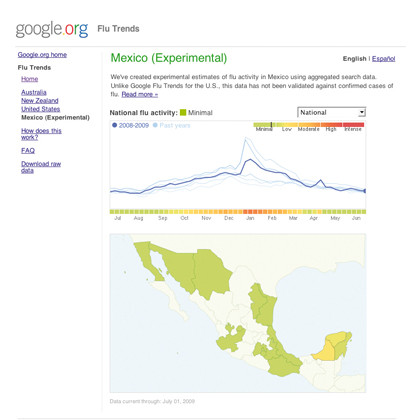

But days before news stations broke the April H1N1 outbreak, Google.org detected an increase in search terms from Mexico related to flu – searches like 'headache' and 'fever'. Months earlier it had released software called 'Flu Trends', which graphs estimates of flu levels in near-real time based on flu-related searches. Now it's angled the software towards Mexico.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

PLOTTING OUTBREAKS: The Flu Trends software shows flu levels based on related searches

A program called 'Experimental Flu Trends for Mexico' ended up graphing the country's flu levels with clear-cutting accuracy before official figures had been made available.

Of course, there are limitations to this approach. Google doesn't have enough data on Mexico's flu levels from the past – a must for estimating current trends – and not enough people in Mexico use the internet, so the system is constantly being tweaked.

Attentive users will notice questionnaires at the bottom of each page when they search for 'headache' or 'fever.' "Did you search for this topic because you have a fever or your friend has a fever?" it asks.

Weeding out those who feel sick from students researching a school project is proving a tough task. But Flu Trends' estimates are still accurate, despite the margin of error. Many believe the spread of HIV/AIDS could have been averted had Africa been monitored more in the 1970s.

That's why Google.org has laid down the motto 'predict and prevent', with the aim of preventing outbreaks rather than just reacting to them. Following that line, it gave a $5.5million multi-year grant to the Global Viral Forecasting Initiative (GVFI) to collect and analyse blood samples of people and animals in Africa and Southeast Asia.

Another $2.5million Google grant to the Global Health and Security Initiative, which works in Southeast Asia, is funding similar detection networks.