Why aren't we all watching TV via the web?

The old broadcast format of scheduled programming should be dead by now.

Time-shifting – recording shows onto a storage device to watch whenever you want, rather than when they're broadcast – and Internet Protocol Television (IPTV) were supposed to have been the final headshot for a medium weakened by repeated blows from 'new' forms of entertainment.

Yet far from living in some nu-mediatopia, we're holding on to old habits. Individual channels and shows may struggle to draw the viewing figures they did a decade ago, but Brits are watching more TV than at any time in the last five years. Blame last year's weather if you like, but the bizarre success of Channel 4's Rude Tube – a chart show consisting of 50 wacky and titillating YouTube clips – suggests that the old guard are having a quiet giggle at the expense of those young 'uns who thought the net would take over the media world.

Think about it: a show whose content is based on online popularity – everyone's already seen it – manages to top an evening's viewing figures during the Christmas period and become a water cooler conversation hit. How? Have we failed, as technology evangelists, to fully express how much better life would be if we chose what we wanted to watch, when we wanted to watch it?

We're sure this idea isn't failing to find its feet for lack of content. There's a huge amount of free video online, ranging from Obama's weekly YouTube address to the comprehensive streams of the BBC's iPlayer. Sky regularly updates its online libraries with the best that Fox has to offer and LoveFilm's download section is improving by the day.

What we lack is an application to aggregate all this media, bringing it together into one manageable place on our desktops like a virtual set-top box. But it's not for the want of trying.

Video on demand

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

The problem is the lack of a single standard for online video. The iPlayer is the gold standard in terms of freedom of integration, exemplified by the large-font web front end designed for Nintendo's Wii, which is outstandingly easy to use on any size of screen.

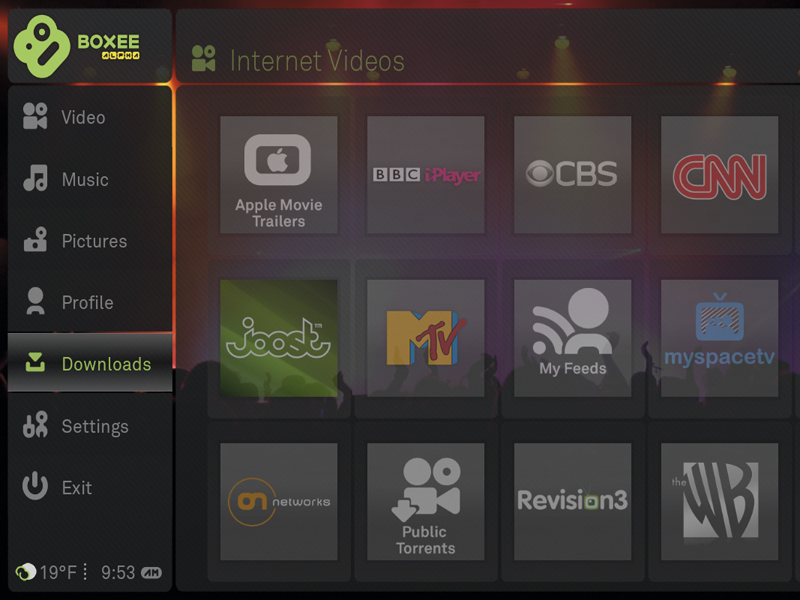

Meanwhile, the Linux and Mac-based Boxee shows off just how different networks could serve up programs using its format. For example, if you select the BBC icon from the list of available sources, the iPlayer controls take over the central part of the browser, leaving the application running on either side. If only the official offerings could be as simple.

Sky's web-based Sky Player, for example, offers a great range of programmes via a browser based interface. Sky subscribers get most of it for free, and buying or renting shows takes just a click. However, in the course of researching this article, it repeatedly threw up an error code, which a helpline operator told us meant that the PC's DRM layer needed to be updated.

Unable to provide a direct link for downloading the code, the best advice that could be offered was: "Search Live.com for it". Eventually, we found the link using Google, but when that didn't work, the response was: "You may need to do it 10 or 12 times". We could have done, but instead we gave up.

It's a similar – although not quite so horriic – story for Channel 4 On Demand, which has some of the most eclectic programming available legally in the UK, but requires a separate instance of Media Player to run and can't be integrated into other feeds. ITV also offers loads of shows that you can view from its website, but this can be difficult to navigate and it's impossible to access from a third-party aggregator. This closed approach to content means visiting each provider individually – so much for the convenience of digital TV.