Don't rage against the machine: humans, not robots, will cause the AI uprising

Should we actually be worried about the singularity?

One of the most enduring threats in science fiction is the spectre of artificial intelligence: the idea that computers will get so smart they'll become essentially conscious... and then try to take over.

From HAL9000 to Skynet to Ex-Machina's Ava, you'd be forgiven for being a little insecure about our continued place in the universe. But do we have actually have anything to worry about, or is it all just scaremongering?

Essentially, the big worry is that with continued improvements in AI we'll eventually hit what has been dubbed 'The Singularity' – the point where AI becomes so smart that it's smart enough improve itself.

And if a machine can constantly create an even better version of itself then it would be like cutting the technological brake cables: computers would quickly be so smart that not only would we be unable to control them, our puny organic brains couldn't even begin to comprehend what they're doing or how they're doing it. Scary, eh?

Is it only a matter of time before the machines take over?

Many of science and technology's biggest names have weighed in with their take on whether we should fear runaway artificial intelligence.

"One can imagine such technology outsmarting financial markets, out-inventing human researchers, out-manipulating human leaders and developing weapons we cannot even understand," wrote physicist Stephen Hawking and his colleagues in the Independent, adding "Whereas the short-term impact of AI depends on who controls it, the long-term impact depends on whether it can be controlled at all."

Billionaire Tesla CEO Elon Musk (below) is so worried about the implications of out-of-control AI that he's put his money where his mouth is, and has donated $10m to the Future of Life Institute, which studies ways to make AI safe.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Bill Gates has waded in too, saying "I am in the camp that is concerned about super intelligence. First the machines will do a lot of jobs for us and not be super-intelligent. That should be positive if we manage it well.

"A few decades after that though the intelligence is strong enough to be a concern. I agree with Elon Musk and some others on this, and don't understand why some people are not concerned."

Of course, this hasn't stopped Microsoft (which Gates is no longer in charge of) investing in some impressive AI research of its own.

Apple has generally been perceived as more reticent about AI, which necessarily involves combing through a lot of our data to train algorithms – something Tim Cook has previously criticised Google for. But this hasn't stopped Apple splashing out on an AI firm of its own.

Just how intelligent are computers now?

Actually, most of the world's largest tech companies are currently hard at work engineering ever more intelligent machines. Google Now and Siri already combine a number of complex technologies, such as natural language processing (understanding what our voices are saying) and semantic text recognition (what our words actually mean).

Facebook has also been experimenting with AI, building a bot it calls 'M' for Facebook Messenger. The idea is that you'll be able to carry out certain tasks, such as booking flights for finding directions, just by talking to it, as though it was a human contact on your Facebook.

The reason much of this smart technology has arrived recently is because the continued exponential increase in computing power, cloud computing and increased storage has enabled the development of advanced 'neural networks' which simulate the same sorts of connections we have in our brains. Neural networks will play a key part in any singularity, as teaching computers to learn is how you teach them to improve.

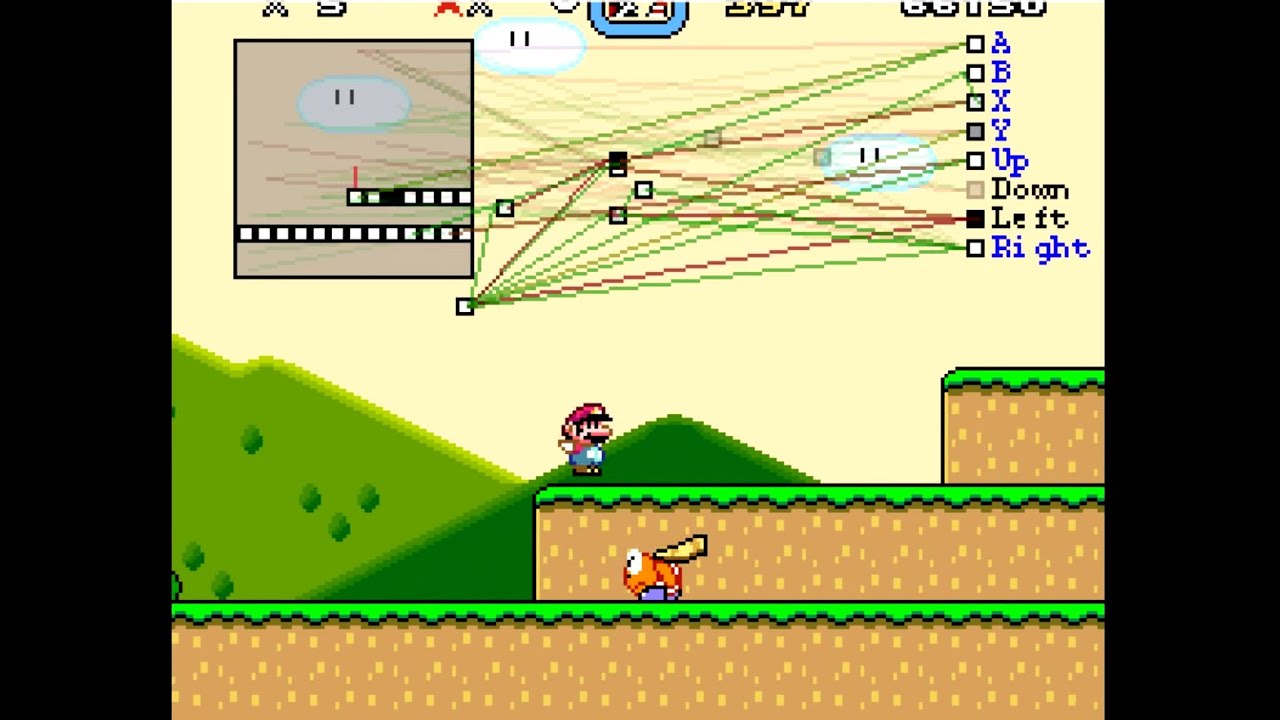

Perhaps the best way to explain neural networks is this video showing a computer learn to play Super Mario World. At first the computer is dumb, but using a process that's similar to evolution by natural selection, it's able to learn and improve. The same principles can be applied to a wide range of things (such as driving a car, or interpreting natural language), the main limitation so far being available computing power – but this is increasingly becoming less of a problem.

The most recent big AI news has been Google achieving another milestone: AlphaGo (powered by its DeepMind project) beat the best human players at the game 'Go', which is many times more complex than chess (the number of available moves in a game is supposedly greater than the number of atoms in the universe).

What the experts say

So should we be worried? Perhaps not. One thing that unites all of the famous names above is that none are actual experts in artificial intelligence – and if you ask the experts, they have a slightly different take.

Mark Bishop, Professor of Cognitive Computing at Goldsmiths University, explained why he doesn't believe, as do the likes of Elon Musk, that we could see 'out of control' AI in the not too distant future.

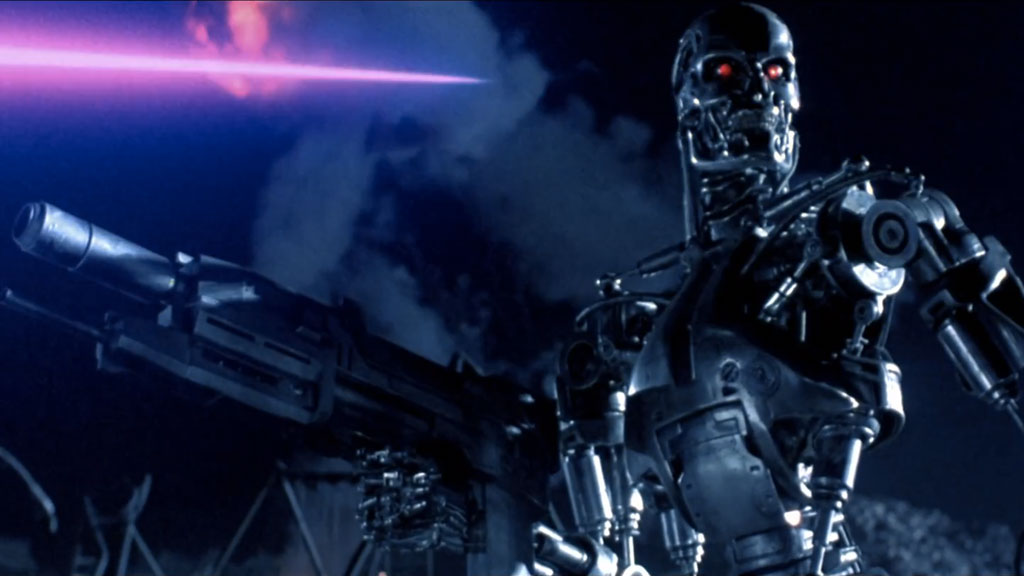

Professor Bishop is well aware of the potential dangers of AI – and specifically the creation of 'autonomous war machines', such as drones that shoot based not on a human deciding but an algorithm.

His worry is that we could be on the verge of a military robot arms race, and last year he co-signed an open letter published by the Future of Life Institute warning against this very thing.

But as for AI taking over completely? Less of a worry. Professor Bishop told techradar: "I remain sceptical of the wilder claims of some of the letter's proponents, as brought up by, say, Stephen Hawking's concerns regarding the 'singularity' or Elon Musk's vision of humanity conjuring up an AI demon within 10 years."

But that isn't to say that there aren't potential problems.

"I certainly do believe that there are extremely serious dangers – perhaps existential – in arming and deploying LAWS (Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems)." Professor Bishop added.

Kersten Dautenhahn, who is Professor of Artificial Intelligence, is also unsure that we're heading for an AI-powered apocalypse.

"I am not worried about AI becoming a threat to people or taking over the world," she told us. "AI has been around since the fifties, and great progress has been made recently in particular, with better and faster (and smaller) computers and computing devices."

Professor Dautenhahn points out that these advances have so far have been "domain-specific". In other words, despite the huge advances we've seen in computing over the last 70 years or so, the intelligence that powers Siri could not power a weapons system, where human brains can do both. This suggests that there's a limit to exactly how intelligent computer code can be – and if there are limits to what a computer can learn, there can be no singularity.

"Even a system that learns and adapts will learn and adapt within the boundaries set by the programmers/researchers writing the code and building the system," Professor Dautenhahn explains. "I can't see any scientific evidence suggesting AI in the near or far future will be a threat to us."

The bigger threat, she says, is us pesky humans. "People using AI in irresponsible ways – this is the real threat. New technology has always been used in benign ways, and in not so benign ways. It's up to us to decide how AI will be used."

So while it might not be the singularity that wipes us out, improvements in AI could still be very dangerous.

Impossible challenges

Professor Dautenhahn also thinks there's another factor limiting the ability of AI to replace us in every aspect of life and eventually take over: interaction. Humans are, apparently, really good communicators – and making machines that can understand the full range of human interaction is very difficult indeed.

This means that if robots hope to replace us, while they might be great at doing sums and so on, they still need to master some incredibly difficult skills.

"Interaction with computers and robots is often inspired by human-human interaction," she explains. "And there is a good reason for this: research in the US and elsewhere has shown clearly that humans tend to treat interactive systems, including robots and computers, in a human-like, social manner."

In other words, we want our robots to be more like us. Professor Dautenhahn says this is why speech and gesture recognition has become so intensely researched – but the technology is still severely lacking. "We do not have a system that can we can smoothly communicate in a human-like way with speech in noisy environments and on any topic we choose", she points out.

Professor Bishop, meanwhile, seems to suggest there's a more fundamental problem: the complex philosophical arguments that underpin our understanding of artificial intelligence.

He believes it comes down to three major things that computers can't do: simulate consciousness, genuinely 'understand' in the same way we do, and demonstrate "genuine mathematical insight or creativity".

So while a robot might be able to win a TV quiz show, as IBM's Watson did in 2011, if Professor Bishop is right we shouldn't expect robots to start writing symphonies or directing plays.

In short, there will always be a space where humans can do more than computers can – or, as Professor Bishop puts it in more philosophical terms: "Because of these shortcomings, it seems to me that a computational system, such as a robot, can never exercise teleological behaviours of its own, but merely act as an agent at its owner/designer's command; such a system could not wilfully disobey a command any more than Newton's apple could wilfully defy gravity and not fall to earth."

Should we be worried?

So will robots/AI replace us? Looking at what computers are already taking care of, to a certain extent it has already happened. Computers are driving our cars, picking our news stories and answering our questions.

But that's not the intelligence we're all worried about – and according to the experts who matter, we've no need to worry about the robots taking over; although neural networks have become increasingly smart, there appear to still be fundamental barriers that will prevent a singularity.

Which is good news for us.

This isn't to say that we don't need to be responsible – as the Professors Bishop and Dautenhahn point out, in the wrong hands, or used for the wrong reasons, intelligent robots could still cause an awful lot of damage – but at least the decision on whether to inflict that damage will probably made by a human, and not an algorithm.