Why don't E-FITs look like actual people?

As if crime's not scary enough, some E-FIT images are genuinely disturbing

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Everyone's seen 'E-FITs' of criminal suspects on the news and in the papers. Grainy and greyscale, or leering unsettlingly with improbable features, it's sometimes hard to see how the suspect could look like the composite and also be a real human person.

For instance, all eight of the nightmare-inducing faces in the main picture above are real e-fits issued by UK police forces, from 'Magic Tardis Hat' (top-right) to 'Rainbow Voldemort'(bottom-right).

Yet at the same time, videogame characters and customizable avatars are better than ever, with some being genuinely recognizable and others a little too close to the uncanny valley: counterfeit-looking humans that give you the creeps with realism rather than rubbishness.

So how come we can make a footballer look pretty damn accurate in Fifa, or perfectly recreate our (idealised) selves in The Sims, but some criminal portraits still look like a comic-book character that was photocopied 50 times?

Feature presentation

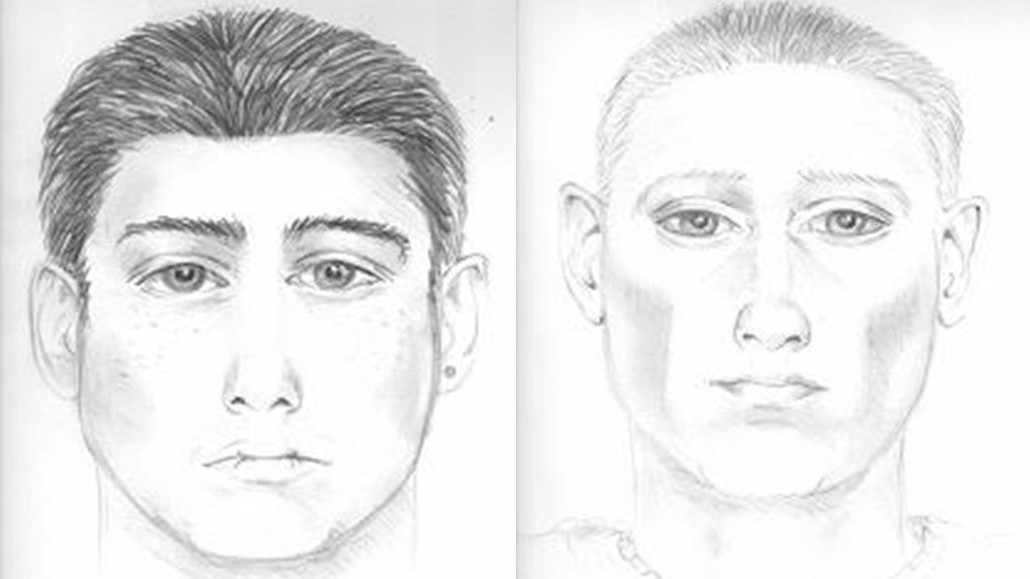

E-FITs have a long history. Originally, trained police sketch artists would hold a detailed interview with a victim who'd got a good glimpse of the suspect, in order to establish their features well enough to make a likeness. This technique is still used today (the two faces below were released by West Mercia Police relatively recently), but understandably, brilliant artists with sensitive interviewing skills are somewhat at a premium, so other methods have developed alongside theirs.

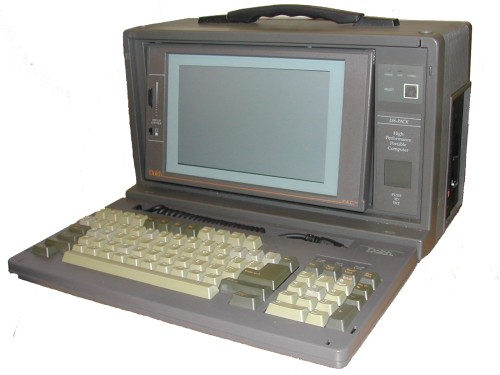

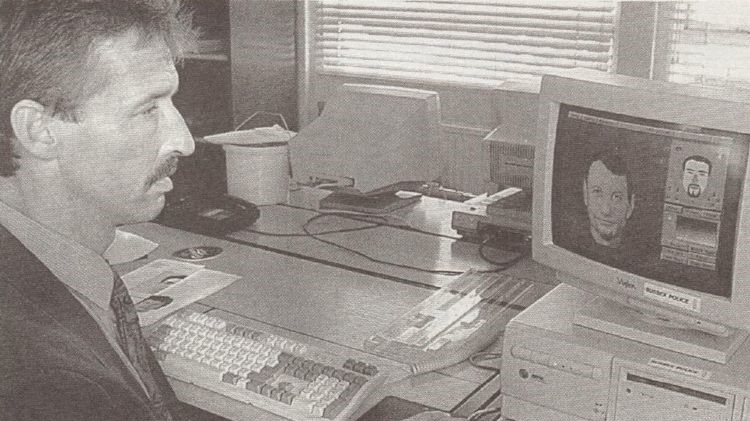

In the 1950s, Identikit was created to help US police forces who didn't have a trained artist available, and involved laying clear strips with creepy disembodied features on top of each other until you made the right face. The Photo-FIT system, based on a similar premise and created by the UK authorities in the 1970s, introduced the 'FIT' name. Then came E-FIT, or 'electronic facial identification technique,' which – before the age of laptops – was impressively created on a portable PC (although it needed a big old tube TV to show the output).

Like Identikit, the early E-FIT systems relied on the premise that someone who'd seen a criminal could accurately remember and describe their individual features, which could then be combined into the right visage. Unfortunately, human beings (with the exception of a small group) don't work that way, and tend to take in faces as a whole.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

In videogames, on the other hand, the artist (or you, if you're creating an avatar) has a visual reference right in front of them. They can see exactly how wide the person's nose is in relation to their mouth, and how deep-set their eyes are, and how all the features are spaced. This makes a huge difference to accuracy: if you perfectly remember all the features of the robber you saw, but get the spacing wrong, it could look like an entirely different person.

Take these examples, from Warwickshire and Dundee Police in the UK respectively, who have some implausibly-sized features:

Even if you're creating a digital version of yourself without a photo reference, you can play about with the nose size slider and the skin tone adjuster until it looks 'about right' (yeah, those shredded abs are pretty close to my doughy stomach, that'll do). So why isn't this the case with E-FITs?

Actually, it kind of is. The E-FIT system has been improved and built on by multiple modern approaches, the key one being E-FITV. Originating at the University of Kent in the UK, and now fully owned by VisionMetric Ltd, this system works much better with the way we see and remember faces – holistically, and there's a sort of nose slider, too.

Facing facts

Instead of combining features one by one, E-FITV starts with a few details about the criminal (age, race, that kind of thing) and generates a set of faces based on them. Then, the witness keeps picking the face that's most like the person they saw, and the system refines and refines until it has a pretty good likeness.

For instance, you might pick face 2 of 9, at which point the system will generate 8 more faces with deviations from that one (a larger nose on one, a different skin tone on another) for you to choose from, until you look at the result and say "that's him".

So what happens if the system isn't generating the face you need? Well, you pick the best fit, then get in there and mess with the details yourself. You can move and scale features, rotate them, add details like wrinkles, and even automatically adjust the age of the face. And if there are two faces you want to smush together, you can do that too.

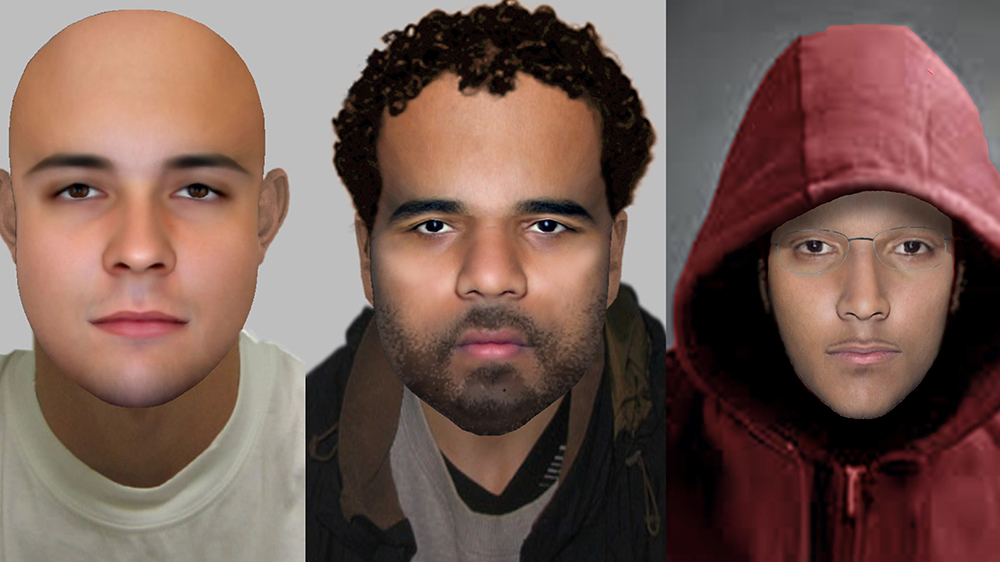

The result is a full-color, detailed, realistic (ish) likeness that's more akin to a videogame character than a bad cartoon. Here are three modern E-FITs recently released by London's Metropolitan Police:

So why don't we see images this good everywhere? Well, firstly, newer systems including E-FITV and the University of Stirling's EvoFIT are proprietary and have a pretty captive market, so they're not cheap. They also require training, which is something most UK police forces are already short on time and budget for. And even with the benefit of training, not everyone's going to be great at operating the software, so some faces will be better than others.

Secondly, we're just not using E-FITs as much as we used to, because tech's intervened in another way. We don't need to rely on fallible human memory if we've got a video of the suspect from CCTV or citizen journalists. So with those stretched budgets, it makes even less sense to invest in new face-making software over, say, a new camera that could get actual photos of the suspect.

That said, there are many police forces, both in the UK and other countries that have made the investment in modern face compositing packages, and that means they should be able to catch more criminals – but we'll have to say goodbye to a rogue's gallery of comedy composites.

TechRadar's Next Up series is brought to you in association with Honor