The inside story of the browser wars, told by a veteran

The creations of Brendan Eich are stitched into the fabric of the web

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The story of Brendan Eich is in many ways the story of the evolution of the internet and the technologies we use to access it. It is also a story of battles won, lost and soon to play out.

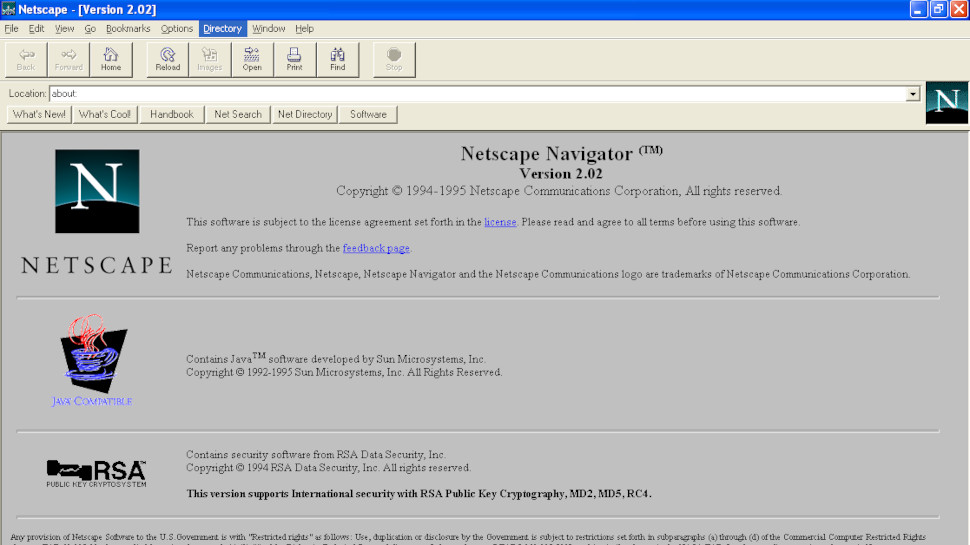

Eich is best known as the creator of programming language JavaScript, which he developed over a sleepless period of ten days in 1995. At the time, he was working for Netscape, whose web browser dominated the market before Internet Explorer spoiled the party.

Recognizing that Netscape had lost its way, Eich spun out another project he had been working on, leading to the formation of the Mozilla Foundation. The organization went on to pioneer the concept of browser extensions with Firefox, which quickly became a household name, before it was crushed under the weight of Google Chrome.

Since departing Mozilla, Eich has focused his attention on a new company called Brave Software, which he believes will help usher in the next landmark period in the history of the internet.

Founded in 2015, Brave is the maker of a privacy-centric web browser by the same name, which blocks both ads and tracking cookies. It is also the proving ground for a novel opt-in advertising model, whereby users are paid for their attention.

With these building blocks, Eich is aiming to bring to fruition an internet characterized not by monopoly and unfettered surveillance, but rather decentralization, disintermediation and individual privacy.

JavaScript is born

Today, JavaScript is deployed across practically all websites, as part of a famous trifecta that also includes HTML and CSS. It allows web developers to code in all the rich features and dynamic content users interact with on the web, and can also be deployed server-side and for various other purposes.

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

Given its ubiquity and the extent of its influence over the web, it’s easy to forget JavaScript is the creation of a single person, who put it together in under a fortnight. “The web was evolving almost in a biological fashion [in the 1990s],” Eich told TechRadar Pro. “My big contribution to the process was JavaScript.”

When Eich joined Netscape in 1995, he says there was a “feeling of doom” hanging over the company, because Microsoft was breathing down its neck. The infamous Microsoft strategy was to “embrace, extend and extinguish”; it would embrace a new type of software, extend it with proprietary facilities that only functioned inside Windows, and harness these new capabilities to extinguish the competition.

The previous year, Netscape had spurned a low-ball acquisition offer from Microsoft, so the company knew it was next in line for the typical treatment. The plan to shield itself relied heavily on the integration of Java into the browser and the opportunities made possible by JavaScript, which was designed as a dynamic companion language that non-expert developers could use to add interactivity to their websites.

“We knew Microsoft was coming after us and we wanted to get Netscape Navigator 2.0 out the door, with Java as the big programming language and JavaScript as the sidekick that let the average scripter glue things together,” Eich explained.

To some extent, the endeavor was a success. Microsoft, which had previously stated its intentions to make VBScript the go-to language for building web applications, was ultimately forced to build support for JavaScript into Internet Explorer. This meant the company did not have control over the favorite scripting language of the web.

Until 1996, Eich was the sole developer working full-time on the JavaScript engine, which was plagued by technical debt (in other words, messy code) that resulted from the speed with which it was first composed. It was also apparent that a specification needed to be created, to guarantee web pages would function as intended across the multiple browsers that now supported JavaScript.

After rewriting the core, Eich helped build out a vendor-neutral specification in collaboration with Microsoft and other players, which was then left under the stewardship of a standards body called Ecma International.

History shows that Netscape was ultimately unsuccessful in fending off the advances of Microsoft, which eventually captured 95% of the browser market with Internet Explorer. Bill Gates had not only made his browser free, but also packaged it with Windows machines, which left Netscape no room to maneuver.

“A bunch of us started to see the writing was on the wall,” said Eich. “The feeling that we were doomed had been fulfilled, and the question became: what next?”

Mozilla breaks free

Knowing itself beaten, Netscape decided to open source its browser code. Eich says the idea was to create a community like the one that surrounded Linux, which would engender new browser innovation.

The company tasked Eich and a group of other developers with setting in motion the project, which came to be called Mozilla. The team worked “inside a fishbowl” at Netscape, at a remove from the rest of the company, Eich explained.

In the coming years, however, the relationship between the Mozilla team and Netscape executives soured. The two groups traded blows over product design, release timelines, the toxic working culture and other topics.

“It was a difficult time,” said Eich. “I stopped using my Netscape email as much as I could and used an ISP email instead. I acted as if I were completely outside the firewall.”

“I also acted as a proxy for the developers we were trying to bring in, who didn’t have the advantage of being employees. Meanwhile, Netscape kept regressing to the mean when it came to the strength of its programmers.”

After a series of layoffs in 2003, Eich and the Mozilla team broke out of their fishbowl to form a standalone non-profit called the Mozilla Foundation, which was tasked with carrying the project forward.

Meanwhile, wounded by the famous antitrust ruling over the bundling of Windows and Internet Explorer, Microsoft had grown lazy with its web browser. The strength of the company’s grip on the market meant it no longer had reason to innovate, creating a window of opportunity for a plucky newcomer.

Despite the politicking inside Netscape, the Mozilla team had managed to build a browser capable of rising to this challenge. The first ever to support extensibility, Firefox (as it came to be known after a series of name changes) rose quickly to prominence and reignited competition in the browser space, says Eich.

Mozilla reaped the rewards of its tenacity in the years that followed, attracting many millions of users to Firefox and netting a lucrative deal that saw Google become the browser’s default search engine. Ultimately, though, this level of momentum proved unsustainable and Mozilla was caught out by developments elsewhere in the technology world.

The rise of the smartphone in the late aughts transformed the way people engaged with the internet, and Mozilla failed to spot the danger. While the iPhone shipped with Safari pre-installed and Android devices came with Chrome, Firefox was left out in the cold. Once again, Eich found himself on the wrong end of the platform effect.

Locked out of the mobile market and unable to compete with Google’s marketing spend, Mozilla could do little to stop the numbers tumbling. Once responsible for roughly 30% of web activity, Firefox now holds just a 4% market share, the latest figures suggest.

Although there were efforts to limit the damage with Firefox OS and other projects, Mozilla never managed to regain a proper foothold and has now pivoted towards other products, including a new VPN.

Eich eventually left the organization under a cloud of controversy in 2014. After less than two weeks as CEO, it emerged he had made a donation in support of a ban on same-sex marriage, and the backlash was fierce. We were told an NDA signed between Eich and Mozilla precluded discussions of this chapter of his life.

Brave new world

While no rational person would dispute the importance of Eich’s contribution to the web, it is also true that he has been on the losing side of both so-called browser wars; first at Netscape, then at Mozilla.

This is a pattern he is hoping to break with Brave, which is pitched as the antidote to the threats posed by Google and its stranglehold on the browser and search markets.

Brave’s browser blocks all advertising by default and has a no-tolerance policy towards third-party cookies, which track users across the web to help inform highly-targeted advertising efforts.

Although there are now plenty of browsers that block invasive tracking techniques, Brave stands apart for its ambitions to rewire the economics that underpin the digital advertising industry.

“The plan was that Brave would be faster, easier on the battery and more private,” said Eich. “And with the help of blockchain technology, we also wanted to replumb the economic engine [of the web].”

The company’s unusual model is built around its Basic Attention Token (BAT), which was launched in 2017 via an initial coin offering (ICO). When an advertiser signs up for a campaign, Brave uses 70% of the fee to purchase BAT from the open market, and these tokens are then distributed to users who have opted-in to the ads program.

Once in the user’s possession, BAT tokens can either be donated to favorite content creators, used for microtransactions with Brave partners, or flipped into regular currency via an exchange.

Which specific ads are served to which specific users is determined by browsing data that is stored on-device and run through a machine learning (ML) model. Apparently, this approach actually yields markedly higher clickthrough rates than the 2% industry average.

Unlike the Google system, which is based on tracking users indiscriminately across the web, the Brave model is opt-in only, compensates the user for their participation and does not involve the transport of browsing data to the cloud.

The signs suggest this strategy is paying off for Brave, which has benefited from increasing awareness of the importance of privacy among consumers. The latest figures show the browser now attracts 50 million monthly users, which is double the figure from a year ago, and quadruple the year before that.

While these numbers are modest in the context of the total volume of web users, Eich predicts that enthusiasm for the service among developers, crypto fans and privacy evangelists is bound to spill over.

“There are privacy nihilists out there that we’ll never convince, but people have generally become more conscious about their privacy as a result of security breaches and events like the Cambridge Analytica scandal,” he said.

“But to breach the chasm to mass market, reaching people who are aware of these kinds of problems matters, because they convert their friends and family, and this creates rolling thunder.”

Empire building

Over the last couple of years, Brave has quietly set about expanding its empire with new privacy-centric products. Orbiting its browser, there is now a Brave VPN, firewall, encrypted video conferencing service, crypto wallet, news aggregator and search engine.

Asked which areas Brave will look to expand into next, Eich declined to provide any concrete information, but did concede the company is “looking at the larger space”. We wouldn’t be surprised to see an encrypted email service from Brave in the near future, for example.

All of these technologies will be foundational to Web 3.0, a new generation of the internet defined by decentralization, disintermediation and greater user privacy. Among those attempting to bring Web 3.0 into being, many believe blockchain and cryptocurrency will play a fundamental role in the transition.

Naturally, Brave has attracted a large number of cryptocurrency enthusiasts, whose ambitions with regards to economic freedom align closely with the company’s attempts to create a more equitable and private web.

The long-term success of the project, however, will be determined by how effectively Brave is able to sell itself to a wider and less technical audience. It has a lot of ground to make up before it can hope to challenge the dominance of Google and other incumbents.

However, as Eich’s story demonstrates, the internet is littered with the corpses of fallen giants. The cry for greater privacy on the web is growing louder and louder, and Brave has put itself in a position to ride the zeitgeist.

- Also check out our list of the best business VPN services around

Joel Khalili is the News and Features Editor at TechRadar Pro, covering cybersecurity, data privacy, cloud, AI, blockchain, internet infrastructure, 5G, data storage and computing. He's responsible for curating our news content, as well as commissioning and producing features on the technologies that are transforming the way the world does business.