Apps: the future of tech or a passing fad?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

App - seldom has such a small word had such a big impact. It's always on the lips of tech's biggest and brightest firms: Apple, Microsoft, Google and BlackBerry. Smartphones, tablets, TVs, fridges, cars: if your devices don't already sport the ability to run small, slick, one-trick programs, then the option is only an upgrade away.

The term has become so ubiquitous that the American Dialect Society - a learned group dedicated to the study of the English Language in America - dubbed 'app' its 2010 Word of the Year.

In case you're interested, it fended off stiff competition from the Cookie Monster's 'nom'. Praise indeed.

But what exactly is an app? Is 'app' really nothing more than a slightly irritating, cutesy term for 'application', or are apps indeed distinct from the software we PC users have enjoyed since the days of DOS? How will they affect the future of computing?

If you're interested in the etymological origins of the word 'app', you can probably thank Apple CEO Steve Jobs. Apple began propelling the word in the popular consciousness in 2008, but Jobs' love of the term dates back to the 1980s and NeXT.

Back then it was one of his favourite terms, presumably due to its friendliness compared to the Microsoft-endorsed 'software program' and the middle-ground 'application'.

A state of mind

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Colin Walsh, owner of Celsius Game Studios, thinks apps aren't so much about a shift in software as about how people think about it:

"We've always had apps in the sense of focused programs that do one thing well. But because of the nature of portable devices, which by their design force a single-app/single-purpose user model, more people and more developers now think about specialised applications."

Walsh thinks this is good, because it's forcing the market away from "bloated monstrosities that do a whole bunch of things poorly," resulting in better software. This in turn engages people who wouldn't otherwise interact with many products, often encouraging them to source their own.

Mat Gadd, a software engineer at Advance IT Group says people in his office have long referred to 'applications', but now his mother - who is in her 50s - has an iPhone 4 and knows what an app is.

"For her Windows PC I had to install software for her, but now she calls me to chat about the latest and greatest app she's discovered and started using on her iPhone," he says.

For developers, this rapid shift in climate is quite a lot to take in, and it points to an unfamiliar future. "As Apple has embraced the mainstream consumer, apps are seen as the same as any other piece of media you can buy through iTunes - a true commodity rather than some artisan creation," explains James Thomson, founder of Mac (and now also iOS) developer TLA Systems.

"Some people will appreciate the craftsmanship involved, and truly excellent software will always find an audience, but we're no longer selling to the same technical hobbyist market we might have sold shareware to a decade or two ago."

Thomson's comment, with its overt consumerist angle, happens to echo the thoughts of Ian Bogost. In his blog post 'What is an app?', Bogost expands on the American Dialect Society's definition of 'app' as "the shortened slang term for a computer or smartphone application" by suggesting that it's also the applications themselves that are shortened and colloquialised.

MAC APP STORE: In making apps simple to buy, Apple has reinvigorated the software market

Instead of software suites - equivalent to a massive CD boxset aiming to cover everything and everyone - apps are more akin to singles. They're bite-sized, one-purpose applications, built for a specific function.

And mirroring what Apple did to the music industry, breaking the market into pieces and giving people somewhere to shop for the bits, Apple broke software into its component parts too, creating an App Store to provide users with a quick-fix solution to almost any problem.

An Apple a day

You might think that, with apps individually being more focused than traditional applications, you'd end up with a more coherent system, but the reality is more complicated.

Due to the typically isolated nature of an app, the notion of system-wide coherence is becoming deprecated in the app age. Logic Colony software developer Krishna Kotecha reckons this distinction between applications and more tightly focused apps will become "increasingly pronounced", although the focus and simple interfaces of apps will let typical users "get the most out of their software".

Certainly, usability has been key from the start with Apple's app model. Walsh argues that Apple "saved the mobile software ecosystem from itself", and says that before the App Store, it was incredibly difficult to sell apps.

The App Store deals with payment and distribution, along with making apps more discoverable. As iOS developer Jedrzej Jakubowski enthuses, "Customers are trained and encouraged to buy apps on a regular basis, which they can do in a very simple fashion."

Kotecha adds that even the much-criticised review process and 'walled garden' aren't a problem. "Unless you want to play fast and loose with platform development rules, private APIs, or user privacy. Apple has done a good job protecting the value of the iOS app ecosystem for both users and developers, because users don't experience the problems that break their PCs, such as malware and spyware. Users aren't afraid of buying and installing apps, and that's a really powerful thing."

Despite coming from the more open Mac development environment, Thomson agrees, and adds that the walled-garden criticism is overplayed: "Apple has found a good middle ground between the PC and games console approaches to software distribution. We can put apps in front of a broad consumer audience, and while there are restrictions, there aren't as many as if you wanted to write for, say, a Nintendo handheld."

A bad Apple

Aside from the well-publicised review process, the App Store has some shortcomings that impact on existing products, but these also point to how Apple may improve its offering in the future.

Thomson would like to see more flexibility in pricing, with the ability to offer upgrades - a common source of friction with users - although he concedes that this this is "perhaps a sign of old-school thinking, given that Apple now rarely offers upgrade pricing on its own products".

Elsewhere, although the app-buying process is discoverable, apps themselves are trickier to unearth due to the sheer number available and Apple's relatively limited search functionality; Thomson notes that many people rely heavily on the charts to 'discover' apps, often keeping a very limited number of products selling well and condemning the remainder.

There's also a tendency for app prices - especially for games - to 'race to the bottom', which has trained users to expect apps to cost 99 cents, or 59p. These needn't be considered entirely bad things.

As developer Neil Inglis points out, "from a consumer standpoint, the two big things are cheap apps and an almost endless supply of apps - I can't remember the last time I looked for an app to perform a task and couldn't find something".

However, because of the difficulty in recouping development costs, there's a tendency for many apps to be very simple, hastening the atomisation of software. This direction means things are going to be tough for any app that's not marketable to a widely understood niche, relegating general or experimental apps to relative obscurity.

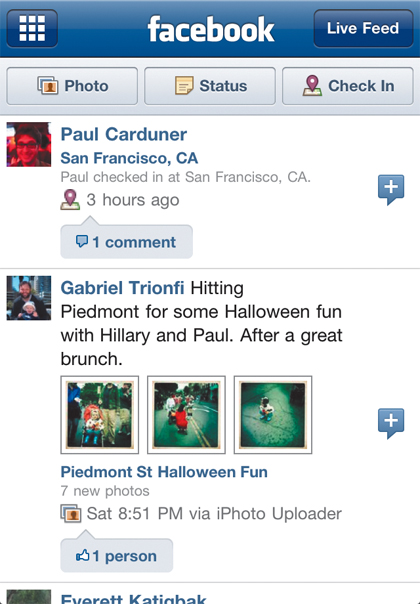

FACEBOOK: Well-designed apps can simplify and improve the user experience of more complex web services

But atomisation can be a benefit to developers and users alike, assuming an app has a real use. As Kotecha explains, "It keeps apps focused tightly on one thing, and focused apps aren't a bad thing at all, because most non-technical users barely use a fraction of the functionality available on their desktop applications."

- 1

- 2

Current page: How apps will change computing and tech

Next Page Bringing the app model to the desktop