Could Brexit damage the UK’s AI industry?

UK must remain 'one of the best places in the world to research and innovate' says report

It's far from clear what the UK's immigration policy will look like post-Brexit, but it's almost certain that stricter controls will come into force in the not-too-distant future.

There's been much talk in the news recently about how changes to immigration policy can affect the technology sector, with leading tech figures in the US penning a letter to president Trump about the impact of his ‘travel ban’ on the industry there.

Now The Royal Society, the UK's national academy of science, has released a report looking at what these uncertain times might mean for the machine learning industry in the UK, and what steps need to be taken to ensure we remain a world leader in this field.

Put simply, machine learning is a process by which a computer can learn to complete a task by looking at previously entered data, rather than by being given a specific set of instructions.

Facebook’s facial recognition software is a good example. The computer doesn’t need to be given individual instructions to identify people in the picture, then facial features, then compare those facial features against a database, then ask if that person is you. It knows it has to identify a person, and runs a system of checks based on previous results to reach the desired result.

Best of British

The UK has a strong track record in the field of machine learning, dating back to the 1950s when the computer scientist and former Bletchley Park codebreaker Alan Turing created the Turing test, a test that's still used today as a marker of machine intelligence.

More recently there have been some hugely successful UK startups dedicated to machine learning, including the now-Google-owned DeepMind, speech recognition company VocalIQ, which is now owned by Apple, and the now-Twitter-owned Magic Pony, which works to process visual data.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Get the hottest deals available in your inbox plus news, reviews, opinion, analysis and more from the TechRadar team.

With the shifts in the current political climate, The Royal Society is keen for the UK not to lose any ground in the world of machine learning, which is a rapidly developing industry.

The report says: “As it considers its future approach to immigration policy, the UK must ensure that research and innovation systems continue to be able to access the skills they need. The UK’s approach to immigration should support the UK’s aim to be one of the best places in the world to research and innovate, and machine learning is an area of opportunity in support of this aim.”

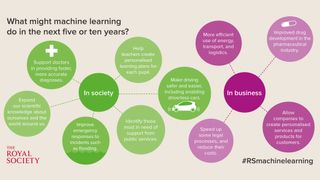

The future of the UK's tech sector fits into a larger conversation about how changes in the digital landscape are going to affect the job market. One of the major fears the study identified during 60,000 digital interactions and 15,000 face-to-face encounters was that machines would replace humans in many jobs.

The report seems to conclude that rather than being a job-taker, this industry is capable of creating jobs, as long as adequate funding is put into education in the field.

“Because of the substantial skills shortage in this area, near-term funding should be made available so that the capacity to train UK PhD students in machine learning is able to increase with the level of demand for candidates of a sufficiently high quality,” the report adds. “This could be supported through allocation of the expected 1,000 extra PhD places.”

One of the interesting discrepancies highlighted in the study was the vast difference between the amount of people who knew what machine learning was and those who use machine learning. Only 9% of all the people asked knew what machine learning was, whereas almost all of them used machine learning in one form or another.

Andrew London is a writer at Velocity Partners. Prior to Velocity Partners, he was a staff writer at Future plc.