How Apple's Magic Mouse works

And why there's no pinch-to-zoom

As with so many spellbinding things these days, Apple's Magic Mouse sadly turned out to be science. iFixit took the Magic Mouse apart as quickly as you'd expect and left us with the below juicy pic of the sensors to mull over.

Inside, we find that Apple has upgraded to laser tracking from the Apple (formerly Mighty) Mouse's optical tracking, offering greater accuracy over more surfaces.

There's also a fairly standard Broadcom chip handling both the processing and Bluetooth transmission duties.

All very well, but the interesting part is the luscious coating of capacitive sensors covering the inside of the mouse's plastic top half.

FULL OF IT: No magic here, just lots of sensors. Also, there is no Santa Claus [Image credit: iFixit]

This is the same type of sensor used in the iPhone, and they work by using the natural electric conductivity of your body to affect the voltage inside the sensors. The principle is similar to plasma globes, where placing your hand on the glass causes the filaments to follow your fingers.

Capacitive sensors are very accurate and highly responsive to even a light touch, though they do have some limitations, as anyone who's tried to use an iPhone in gloves can attest. That generally isn't a problem indoors, so they're ideal for desktop interfaces.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Get the hottest deals available in your inbox plus news, reviews, opinion, analysis and more from the TechRadar team.

Using sensors all the across the surface and down to the Apple logo is a crucial part of making the mouse live up to Apple's usual standards for accessibility. Having an invisible line where scrolling just stops working would confuse people no end, so it's important that Apple hasn't skimped here.

Apple brags about the Magic Mouse's ability to differentiate between gestures and resting your hand, and this is all done in the software that accompanies the sensors.

We're admittedly simplifying here, but essentially it's a standard database query. When your fingers touch the sensors, the software asks itself whether what you've done matches up to being a scroll – moving one finger consistently in recognised direction – or whether it matches up to a swipe – two fingers moving quickly in recognised direction. If the input doesn't conform to either of these then it can safely be ignored.

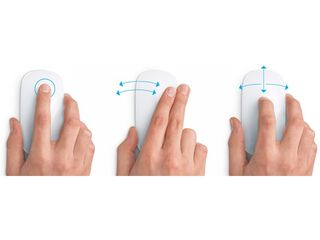

DIFFERENT MOVEMENTS: Sensors are located all across the surface to pick up different gestures

The accuracy of capacitive sensors allows for advanced software features like momentum scrolling. The speed of your finger movement is always carefully measured, and if you lift off while moving then the scrolling simply continues at that speed before running down.

It's the combination of the sensor hardware and gesture software that is key to the bringing devices like the Magic Mouse to life. So can we expect more of them in the future?

Synaptics specialises in capacitive sensors and gesture recognition software. It makes a type of sensor that is flexible enough to fit in curved enclosures, works under a plastic shell and comes with gesture software that recognises only scrolls and swipes.

We don't know if this is the exact technology used in the Magic Mouse because Apple doesn't talk about its suppliers, though it would explain why pinch and rotation are missing from the new mouse.

What we do know is that functionality similar, if not identical, to the Magic Mouse's is available for anyone to licence. Indeed, Microsoft has already shown off a multi-touch mouse concept bearing the telltale lattice of capacitive sensors.

SECOND PLACE: Microsoft showed off its multi-touch concepts first, but Apple has beaten it to market [Image credit: Microsoft via PC Mag]

Things are never that simple, though. Apple not only owns the trademark on the name Multi-Touch, but has also filed patents relating to "a computer mouse having a touch-sensitive shell capable of accepting multi-touch finger gestures" (as described by Apple Insider).

It seems unlikely that these potential barriers will stop more multi-touch mice appearing before too long, but Apple has certainly laid down a marker for how we will interface with this generation of multi-touch capable operating systems.

Most Popular