Can Facebook and Twitter exist without fake news and trolling?

The dark side of social media might just be intrinsic to the format.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

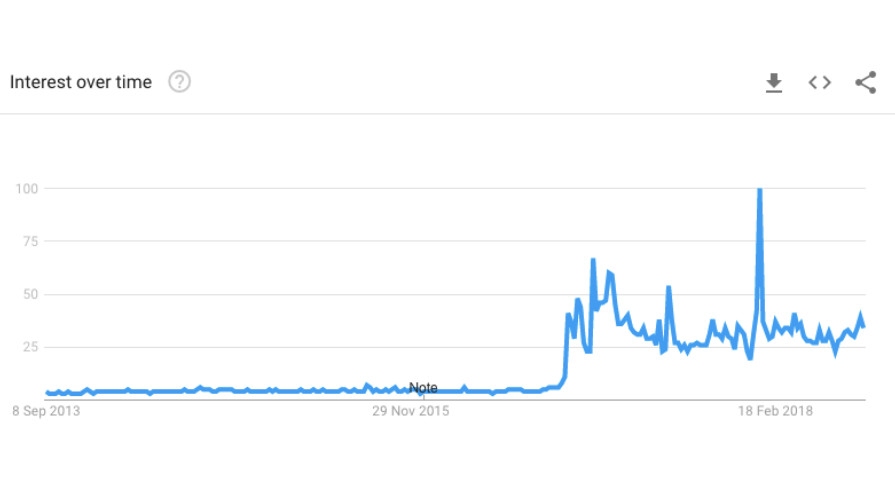

There was a time when 'fake news' wasn’t part of the internet lexicon. As Google Trends shows, that changed on November 8 2016 when Donald Trump was elected president of the United States, and it has been part of our collective vocabulary ever since.

That correlation is no coincidence. As people tried to come to terms with the biggest upset in modern political history, social media was given a more thorough examination that it had ever had to endure. After a tortuous period of denial, Facebook accepted it had a problem with Fake News and Twitter an issue with trolling – something ironically exacerbated by the new Tweeter-in-Chief, who successfully co-opted the term ‘fake news’ as a catch-all for critical reporting, rather than the conspiracy-loaded clickbait his predecessor described as “a dust cloud of nonsense”. Both platforms have vowed to clean up their acts.

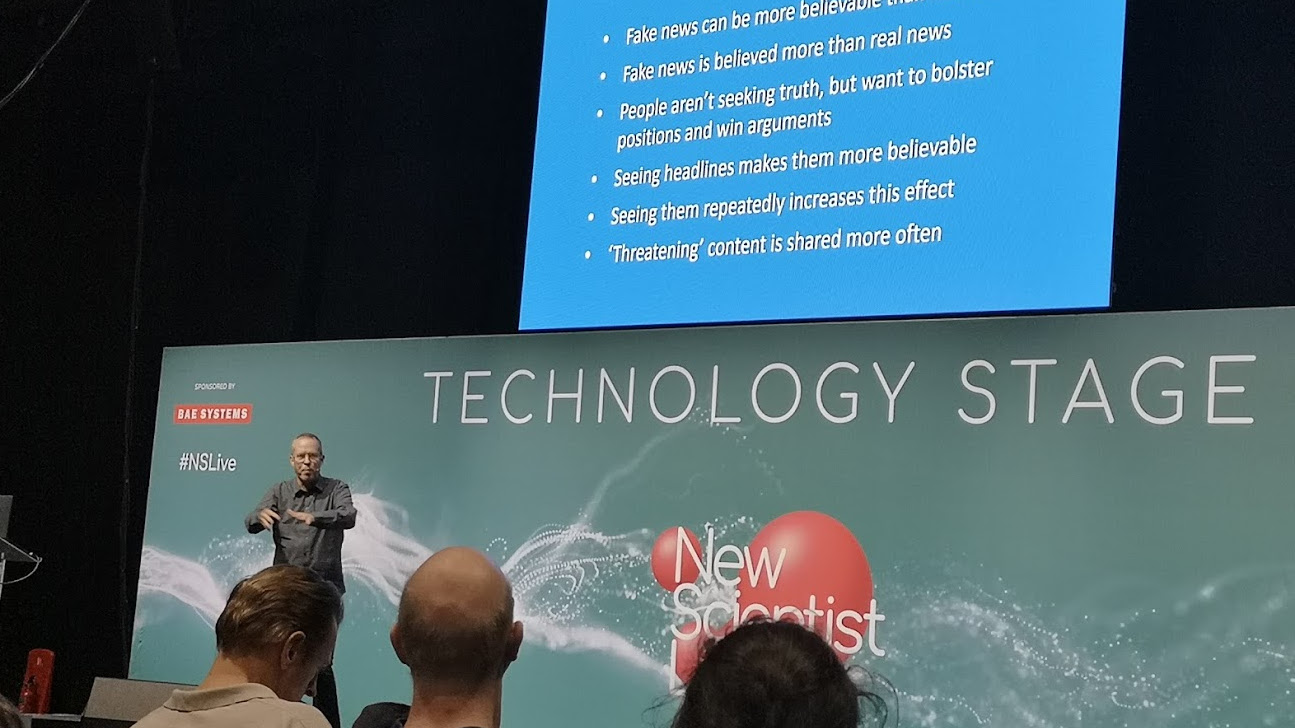

But what if trolling and fake news aren’t bugs to be eliminated, but intrinsic features of social media? That’s the contention of Professor Paul Bernal, from the University of East Anglia. “If we want to address these issues seriously, we have to understand that it's not that these are bad people misusing the systems, but these are actually inevitable consequences of the way that the systems work,” he says in a phone interview ahead of the talk.

For Twitter this is down to it being, at its heart, a conversational medium – and an open one at that. “In terms of trolling the problems here are many-sided,” he explains. “How do you define what counts as trolling? If you do it algorithmically, the algorithms make hideous mistakes. The wrong things get banned and the really clever trolls use passive aggressive language, they find clever ways to avoid detection.

It's not in Facebook's interests for stuff on Facebook to be unemotional. You could say they don't want boring stuff on their platforms, which sounds good, but actually it means they're more likely to encourage the bad stuff

Professor Paul Bernal

“It's really hard to deal with the nuance, and the trolls find their way round, and they try to encourage things that will get others banned – and it works!”

For Facebook, it’s a little more complicated and is partly down to the way it’s evolved. “Facebook is a place where information is presented to some degree, and that gives an opportunity to present the fake news,” Bernal says, citing empirical evidence which demonstrates that content is more likely to be shared if its fake and/or threatening.

Facebook’s emotional contagion experiment showed it could affect mood with the type of news that appeared in feeds. But Bernal feels something important was missing from media analysis: without happy or sad news, engagement plummeted. “It's not in Facebook's interests for stuff on Facebook to be unemotional. You could say they don't want boring stuff on their platforms, which sounds good, but actually it means they're more likely to encourage the bad stuff,” he continues.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

That’s not ideal, but it becomes more alarming when combined with the data collection where Facebook continues to make its money. “We've developed systems – and Facebook is the most obvious – which are incredibly efficient at finding out what people are interested in, finding out how you might be able to nudge them in a specific direction, and automatically pushing material to those people,” Bernal explains.

In the wrong hands, these two points – knowing not just which person to target, but the emotional buttons to press – combine to make what Bernal sees as a perfect storm of exploitation. One that’s impossible to counter without radically changing human nature or Facebook’s financial model.

This echoes what technology historian Professor Marie Hicks told me a few months ago when I asked for her thoughts on fixing social media. “It assumes what we have here is just a bug that needs to be fixed, rather than a poor feature of the system,” she said after a panel discussion at Nesta’s Futurefest. “If you think that is a fundamentally a business model you want to get – the ad-driven services we have – then you're left with very few options of how to solve the issues that have become a flashpoint.”

Honeymoon period

The counter to this, surely, is in our memories: weren’t Facebook and Twitter once untainted by these problems? Bernal concedes that’s true, but now the genie is out of the bottle, he says, those days simply cannot come back. “There was a honeymoon period for both – when Facebook really was about linking together families, and Twitter for chatting,” he responds. “The underlying problems were there, but they weren’t being taken advantage of.” The increased scale and opportunity for political mischief put paid to that: “Once the potential was seen, it was inevitable.”

Indeed, the power of fake news and threats have been apparent throughout history, and Bernal will point to Vlad the Impaler in 15th century Romania in his talk. “They used woodcut pictures cut into pamphlets that were distributed by hand within the community,” he explains, and these exaggerated caricatures ensured Vlad’s reputation preceded him, even for a largely illiterate population. Nowadays, the internet-connected world may be largely literate, but it’s not necessarily internet-literate when it comes to judging content.

“You can create a fake news page in seconds,” Bernal laments, “so if they shut them down individually they're onto a losing game of whack-a-mole.” Likewise, the softer approach of labelling things as fake was abandoned. “Highlighting things makes people more likely to look at them, and looking at things makes people more likely to believe them,” Bernal explains. And that’s before you even get into the thorny issues of who should be the arbiters of truth: the flawed, biased algorithms or the flawed, biased humans?

Even if Facebook took the age-old advice of avoiding politics and religion in polite discourse, Bernal believes the company would still provide a bridge to fake news peddlers. “Evidence shows that you can derive the most sensitive information from the most mundane sources,” he says, highlighting the surprise correlation between curly-fry fandom and intelligence. Ban political ads and “the clever ones just go one step back”, working on “the predictor rather than the politics.” You can see early work being done in this ‘one step removed’ field with the diverse array of political adverts the Vote Leave campaign was shown to have bought on Facebook, targeting everyone from polar bear lovers to football fans.

Hicks shares Bernal’s pessimism. “People who thought the internet would be a source of unmitigated good were just ignoring the past,” she told me when asked if she was optimistic about the internet’s future. “This was a military technology that was specifically designed for certain military ends - and yes you can repurpose it to be a really powerful informational tool, but that is a repurposing. You're not designing a technology that is somehow intrinsically good.

“If you subscribe to the idea that the internet is a global good, I think we've hit the high point of that optimism and things are going to slide down from here.”

The people's Facebook

Imagine a different world where MySpace or Bebo became the dominant force of the social web. Would the fake news problem still exist? That question, Bernal reckons, has a flawed premise: the eventual winner was always going to be the one that made money from personal data. “Whoever won was going to be the one that was good at fake news."

And, as Hicks pointed out, the stakes of that battle were huge, even though nobody knew the fight was going on at the time. Tech companies are “so powerful and are controlled exclusively by corporations so they become pseudo-governmental, even though they're completely outside of any process of democratic input,” she said.

Bernal agrees: “We've privatized these systems, and done so in such a way that they're controlled by a relatively small amount of people,” he says. The open 'marketplace of ideas' required for the best free speech to flourish is too closed to function, and it’s not in the big players’ interests to reverse that.

OK, so what about regulation? There are pitfalls here. Not only do Facebook and Twitter operate across borders in an era where nations are becoming less cooperative, but that while technology moves fast, law and government moves at a pace that some glaciers would consider plodding. “By the time you've sorted out some system to regulate this, everything will have moved on,” Bernal argues.

Hicks, too, wonders if there’s any appetite for governmental pressure beyond idle threats. "In the United States where most of these companies are headquartered, we're in a very anti-regulatory moment,” she explained. “And we're under an administration that has been really helped by the power of these platforms and probably doesn't want to give that up.

To what extent should governments be involved in making sure corporations do the right thing? Would it be even worse if governments emerged as a censor? Neither option is at all palatable

Professor Paul Bernal

“I think that the right sort of questions are starting to be asked, but I don't think we have any of the mechanisms necessary to make those changes right now.”

What about a radical rethink? The day before I speak to Bernal, leader of the British Labour Party Jeremy Corbyn floats the idea of a nationalised social network: a BeboC, if you will. Although widely lampooned, is it really stranger than a nationalised rail network?

“Frankly, nationalize Facebook and you kill it,” Bernal replies. Providing a transparent service that has “all of the good things with none of the bad” and “without the perverse incentives from monetization” betrays an expectation that what Facebook is now is what it will always be.

“I'm not on Facebook myself, deliberately for all these reasons, but what makes it attractive, what makes it innovative and what makes it work is very different from providing some kind of national platform for communication,” he explains. “It would soon get boring; it would go the same way as Friends Reunited.”

There’s also an element of being careful what you wish for here, and a look over at China shows you where things can go with too much government interference. “They don't have to create fake news,” Bernal points out. “They can just prevent the real news from appearing.”

“To what extent should governments be involved in making sure corporations do the right thing? Would it be even worse if governments emerged as a censor? Neither option is at all palatable,” Bernal argues.

“There isn't a simple way out here.”

The devil we know

Even without slipping into authoritarianism, there’s every chance governments could make things worse via the law of unintended consequences. “We don't really understand what threads that we might pull, what those effects are going to be even five years, 10 years in the future,” said Hicks. “The thing with the US elections – it snuck up pretty quickly, and then it was a matter of looking backward and trying to figure out what was going on.”

That’s true. In an alternate reality where Hillary Clinton is sitting in the Oval Office, it’s hard to imagine scrutiny of Facebook picking up any traction at all. And if you accept that, it’s hard to argue that any government action now wouldn’t be at least partially motivated by sour grapes.

Facebook hasn’t responded to my request for comment beyond an initial acknowledgement and Twitter has yet to respond at all, but their public actions to date have been more theatre than practical in Bernal’s eyes.

“I suspect with Facebook and Twitter, they're mostly flying by the seat of their pants,” he says. “They're doing what they need to do to keep their businesses rolling and they're reacting when they need to react, but would rather do as little as possible and let the systems run by themselves.

“Algorithms are cheaper than humans,” he says. “I don't think they're as much in control as we think,” he adds, stating that there’s no great conspiracy here. But crucially a lack of malign intent doesn’t prevent their actions from having “massive implications”.

Is there anything positive on the horizon? Yes, but you have to optimistically squint and claim the glass is 10% full: “We are at least in a productive moment of critique,” Hicks said, pointing to the lively debate going on both inside and outside the industry. She predicts “significant changes in the next 5-10 years”.

If there’s one thing we’ve learned in recent years, it’s that change isn’t always for the better. Does she subscribe to the idea that history repeats itself? “I don’t think history repeats itself,” she smiled, “but it rhymes.” Wherever you stand politically, that’s something to bear in mind when party machines ratchet up their social media spend for the next big campaign.

Alan Martin is a freelance writer in London. He have bylines in Wired, CNET, Gizmodo UK (RIP), ShortList, TechRadar, The Evening Standard, City Metric, Macworld, Pocket Gamer, Expert Reviews, Coach, The Inquirer (RIP), Rock Paper Shotgun, Tom's Guide, T3, PC Pro, IT Pro, Stuff, Wareable and Trusted Reviews amongst others. He is no stranger to commercial work and have created content for brands such as Microsoft, OnePlus, Currys, Tesco, Merrell, Red Bull, ESET, LG and Timberland.