Beyond haptics: blurring the line between your virtual avatar and your body

The pursuit of virtual embodiment

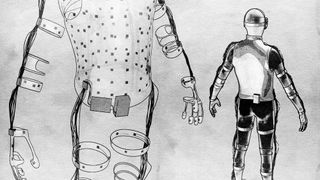

Main image credit: Teslasuit

In the space of a few short years, virtual reality has gone from being a technology of the future to part of the mainstream. Devices ranging from the humble Google Cardboard to the Oculus Rift have invaded our living rooms, and VR is set to transform everything from education to the sex industry.

But if VR is to achieve the mass appeal many are predicting then it needs to feel, as well as look, as real as possible, and not just like we’re passively watching a TV set strapped to our faces; the rest of our body needs to be as engaged as fully as our eyes.

Let’s get physical

Enter haptic technology, which allows us to literally feel what we’re experiencing in VR. You’ve likely come across haptic tech, sometimes referred to as just ‘haptics’, before, for example when you’ve played a video game and felt a rumble in the handset.

Now companies like Tesla Suit and Hardlight VR are bringing that experience to your whole body, with suits that can move and shake and vibrate in specific areas as you explore virtual worlds.

But let’s slow down for a second. We have to because this haptic tech is far from becoming mainstream and, crucially, you can’t just put a haptic suit on someone and expect a VR experience to feel real.

That’s why there’s a lot of research going on into what’s known as ‘virtual embodiment’.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Get the hottest deals available in your inbox plus news, reviews, opinion, analysis and more from the TechRadar team.

This is a complex and fairly new area of study, but it’s concerned with using technology, virtual representation, avatars, storytelling, haptics and all kinds of other subtle visual, auditory and sensory cues to make you feel like you’re inhabiting another body. Whether that’s an avatar of yourself, someone else or even something else.

Check out the video below to see the Teslasuit in action!

Exploring the body/mind connection

Virtual embodiment might be a new area of study, but it’s built on research about the connection between our minds and our bodies that goes back more than a decade.

One example is what’s known as the ‘rubber hand illusion’. This was an experiment that essentially proved that, with the right stimuli, people took full ownership of a rubber hand as their own.

Fast-forward to the present day and similar studies have put the rubber hand illusion to the test in a VR setting.

In a 2010 study, researchers found that synchrony between touch, visual information and movement could induce a believable illusion that people actually had full ownership of a virtual arm.

Similar studies have looked at the efficacy of using avatars for rehabilitation and visual therapy, with research suggesting that, in most cases, our virtual bodies can feel as real as our physical bodies.

Defining virtual embodiment

To find out where the research is right now, we spoke to Dr Abraham Campbell, Chief Research Officer at MeetingRoom and Head of the VR Lab at University College Dublin.

“Virtual embodiment is a difficult thing to define as it can mean a lot to different people in different fields,” Campbell explained. He proposes that we look at virtual embodiment in three categories, all of which are a modified version of Tom Ziemke’s work on embodiment.

“Firstly, structural coupling is the most basic and classic definition of embodiment,” Campbell told us. “You’re connected to some form of structure. For example, a body. You move your limb in real life, and a virtual limb moves mimicking your actions...you are embodied within the VR world.”

Campbell offers the example of moving the HTC Vive controller in the real world, and that becoming a hand that’s moving in the virtual world.

Next up is historical embodiment, which is when the VR world you enter ‘remembers’ what’s happened in the past. Campbell uses the example of drawing on a white board, when what you’ve drawn stays there when you return in a day, a week or year from now.

“Finally, social embodiment is when you interact with real or artificial entities within the VR world,” Campbell says. “These interactions have to be behaviorally realistic, so you feel that your body is able to interact with them in the environment.”

And why is studying embodiment important? Campbell explains: “The more embodied the agent or human is within the environment, the more capable they are of interacting and sensing that world.”

Social interaction and education

Campbell’s main focus is on social collaboration in a recreational and educational setting.

“I’m examining the use of telepresence and VR in education, and exploring how I can remotely teach from Ireland to China using technology like Kinect [Microsoft’s motion-sensing input devices for its Xbox game consoles] to scan me in real time, while at the same time view the classroom in China using a set of projectors,” he said.

Bringing a teacher into a distant, virtual classroom will certainly be useful. But the next challenge is working on the intricacies of social interaction, such as facial expressions.

”Being able to convincingly communicate with others in a face-to-face way at a distance is one of the most exciting possibilities.”

Dr Gary McKeown

And although interacting with people may not sound like the most interesting use of virtual embodiment, it’s one that’s bound to get attention.

“It is also clearly an industry goal,” Dr Gary McKeown, Senior Lecturer at the School of Psychology at Queen’s University Belfast, tells us. “It is not a coincidence that the company with the most to gain from making the social interaction aspects of virtual reality function well – Facebook – is the one that bought Oculus.”

Remote instruction

Imagine being able to remotely control machinery, or just help out family fully from thousands of miles away - it would change so much about work, commuting and social interaction.

This is one area that’s particularly interesting to Campbell is using embodiment research to aid telepresence or telerobotics, which is the use of virtual reality or augmented reality (AR) to do just that.

“I’m fascinated by Remote Expert, which is being pioneered by DAQRI,” he told us. “This allows an expert in a field to be remotely placed in augmented reality beside a non-expert to perform a complex task. DAQRI are looking at medical and industry fields to apply this technology, but you can imagine lots more applications.”

Campbell explained that one of the many uses for this kind of tech could be if an oil pipeline bursts, and the engineer who designed it is in another country. A local engineer could go out to fix the pipeline , with the designer advising them in real time using VR or AR and a stereo 360-degree camera.

As we learned above, the tech enables the presence element of this. But where embodiment research comes in is making it more engaging, more realistic... ultimately more real, and with it the power to really offer help unhindered by technology.

Campbell explained: “The remote expert needs to be able to use hand gestures to demonstrate what the non-expert should do.

"The expert should be scanned in 3D in real time along with the remote world they are being placed into. This embodiment will allow them to truly be able to assist in whatever complex ask they’re asked to perform.”

The implications of this are massive, and could radically change a number of industries.

NASA already has a telerobotics research arm that’s looking at using this technology for space exploration, and it’s being introduced into other fields, from engineering to medicine.

Campbell believes this kind of telepresence will have a big impact on the medical industry as technology advances too.

“One solution I hope to explore in future is to use a full hologram projector pyramid,” he told us. “This approach has been suggested to me by medical professionals who want to meet patients remotely by using a full size projector pyramid [i.e. one that’s about two metres tall]. With this kind of tech, the doctor will be better able to diagnose a patient.”

Therapy and rehabilitation

Virtual embodiment doesn't just have huge implications for exploring physical presence, but mental and emotional presence too.

In a 2016 study, researchers discovered that virtual avatars that look like our physical selves can help people feel a sense of embodiment and immersion that it’s believed could enable them to better work through mental health challenges, as well as real-world trauma.

VR software developer ProReal uses virtual environments containing avatars to play out scenarios that help people deal with a range of challenges, from bullying to PTSD and rehabilitation.

As the tech advances, it could provide a whole new area of therapy for those who aren’t getting the results they need from talking therapies or medication.

But it’s not just more serious mental health challenges, like PTSD, that can be explored; avatars can be used to increase confidence or change our perception of ourselves. Campbell told us about the time he noticed that those with bigger avatars felt more powerful.

“One accidental discovery I had, when I looked at games in VR, was that when the avatar is on average one foot taller than the other characters, it makes the player feel more powerful than the computer-controlled characters,” he explained.

That observation mirrors a 2009 study in which researchers found that those given taller, bigger avatars behaved differently and more aggressively in interactions with others.

So aside from therapy and mental health use cases, it’s possible to imagine VR being used in corporate settings, to make people feel more confident before presenting to a boardroom.

The challenges of embodiment

If it’s easy for researchers to think of creative ways in which embodiment could have a positive impact on our lives, it’s not much of a leap to consider the negatives too.

Some tech commentators believe social isolation could be an issue as the use of VR headsets becomes more widespread and experiences become more immersive, a concern that’s likely to become more prevalent in gaming.

But many within the industry believe the focus on social isolation is just scaremongering.

“I haven’t witnessed people feeling isolation,” Campbell explained. “Even students who are interested in VR for pure escapism want to share it with others afterwards, and have become evangelists for VR in its ability to be an empathy machine, as with embodiment you can truly get a sense of seeing things from someone else’s perspective.”

Another important talking point is around dissociation or detachment from your own body after exploring virtual worlds. There’s been very little research in this area, but one study from 2006 found that VR can increase dissociative experiences, especially if you’ve been immersed in a virtual world for a long time.

More than a decade on, and with better VR technology and content it’s no surprise that lots of anecdotal evidence points to a similar ‘post virtual reality sadness’, in which the real world doesn’t quite compare.

One potentially problematic side-effect Campbell thinks we do need to consider right away is addiction. But he explains that, unlike with traditional gaming addiction, VR can be designed differently.

“In VR, the user needs to replicate the real-world actions and thus shortcuts the traditional dopamine-hit reward cycle that people often become addicted to,” he told us.

So, for example, if you win a gaming level within VR you’ve likely put a lot of physical effort and exertion in, perhaps by killing the big bad boss at the end of the level. You’re likely to be physically tired. That’s the difference.

Of course you can still get addicted to that feeling – people get addicted to working out – but Campbell tells us: “It’s the responsibility of game designers to make sure that VR games reward a player for real effort and not make a game that’s hard at first to complete, but then actually gets easier.”

We spoke to Sol Rogers, the Founder and CEO of creative agency and VR production studio Rewind, about some of these concerns.

“We’ve studied how humans interact in and with the real world for hundreds of years, and we’ll probably need the same amount of time to study how humans behave in VR and what the implications are,” he told us.

But he urged people to be excited about the prospect of what VR can do, not scared. “While we can only speculate about the impact VR will have, we need to progress with watchful caution rather than hysteria,” he added.

“Self-regulation from content creators is key, but a governing body also needs to take on some responsibility. Ultimately we need more research, and more time, to fully understand the implications.”

The recipe for greater embodiment

But embodiment is only convincing if everything else in the experience is up to scratch. We asked Rogers about how his team works with tech to create the most realistic experiences.

“Achieving a lifelike user experience in VR is now possible because of tremendous advancements in computer processing power, graphics, video and display technologies,” he told us.

“But the tech needs to stay out of the way; it needs to be entirely inconsequential to the experience, otherwise the spell is broken.”

”The tech needs to be entirely inconsequential to the experience, otherwise the spell is broken.”

Sol Rogers, CEO of Rewind

And he adds that the tech is only half of the equation; his job is to ensure the content is telling the best possible story, every step of the way. “Content is also key to creating presence. While the tech is no doubt important, no user is going to suspend disbelief if the experience is awful.”

From entertainment and social interaction to engineering and performing medical procedures, the more we understand, test and implement embodiment experiments, the more we can engineer experiences to feel real – and in turn be more effective.

With advances in research from the likes of Campbell and his team, along with advances in tech to make headsets slimmer, sensory feedback easier to implement and full-body holograms a reality, the sky is only virtually the limit.

This article is brought to you in association with Vodafone.

Becca is a contributor to TechRadar, a freelance journalist and author. She’s been writing about consumer tech and popular science for more than ten years, covering all kinds of topics, including why robots have eyes and whether we’ll experience the overview effect one day. She’s particularly interested in VR/AR, wearables, digital health, space tech and chatting to experts and academics about the future. She’s contributed to TechRadar, T3, Wired, New Scientist, The Guardian, Inverse and many more. Her first book, Screen Time, came out in January 2021 with Bonnier Books. She loves science-fiction, brutalist architecture, and spending too much time floating through space in virtual reality.