"Weirder than Bill Gates and Steve Wozniak put together": Japan's answer to Steve Jobs predicted personified computers, smartphones and AI in 1984 through a sixth sense, viewing the world as a dog or a dolphin

Sunao Takatori did not think like his Western contemporaries

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the early 1980s, while Silicon Valley was still arguing over GUIs, disk drives, and whether people would ever want a mouse, 25-year-old Sunao Takatori, a Japanese software designer, was quietly describing a future that looks uncannily like 2026.

In 1984, Alexander Besher, contributing editor at InfoWorld, traveled to Japan to meet Takatori, who was at that time the founder of Ample Software. In his article, published in the May 28 issue that year, Besher described Takatori as “a lot weirder than Bill Gates, Gary Kildall, Mitch Kapor, and Steve Wozniak put together.”

That “weirdness,” viewed four decades later, looks a lot like foresight.

Article continues belowThe sixth sense of software

Besher met Takatori in a private room at a restaurant in Shibuya, “high-tech with a dash of soy sauce,” as miso soup was served and pickled radish passed around.

Takatori was already successful by early-1980s standards, having grown Ample Software from ¥1 million in revenue to ¥100 million in a year, producing custom software for NEC, Fujitsu, Toshiba, Pioneer, and ASCII-Microsoft. But business success was incidental. What mattered was his obsession with artificial intelligence.

“My dream is to build a home-computer system capable of understanding human feelings,” Takatori said. In 1984, when most home computers barely understood file systems, this was a startling ambition.

Takatori believed that conventional engineering thinking was fundamentally incomplete. “As far as Takatori is concerned,” Besher wrote, “the five senses convey only a partial reality.” Takatori believed that great software designers relied on something else entirely.

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

“I can see the changing trends of the industry,” Takatori said. “I sometimes can visualize the next generation of computers in vivid colors as if the images are a fast-motion picture on a color TV screen.”

He called this intuition a “sixth sense,” and he took it seriously enough to train it deliberately. One of his methods was to abandon human perception altogether.

“A car appears as if it were a gigantic and distorted building,” he explained. “I now see the world through a dog’s eyes. Everything I see, even pebbles and discarded chewing gum stuck on the road, has a unique and interesting appearance. It’s a lot of fun to take a walk from Shibuya to Shinjuku on all fours at a dog’s eye level.”

This wasn’t metaphorical. Takatori genuinely believed that shifting perspective, essentially inhabiting non-human viewpoints, was key to designing future software. Sometimes, he went even further.

“I am swimming in the ocean. Only my eyes are sticking out of the water. I’m now familiar with the dolphin’s vision. I’m extremely pleased with this discovery. Then I wonder how I can express the world as seen from different visual points.”

In 2026 terms, this sounds like multimodal AI design: systems trained to interpret the world through different sensory frames, not just text or numbers, but vision, sound, emotion, and context.

“It is amusing to imagine invisible entities,” Takatori said. “If I discover something new in the process, then somehow I would like to convey it in order to share the experience with others. I believe that software is the best means to express such a discovery.”

Predicting personified computers

Takatori was deeply skeptical of the personal computer as it existed in 1984. He did not believe beige boxes with keyboards would ever truly penetrate society.

“Eventually polarization will take place,” he said, “after a period during which the functions of the telephone, TV, and analogical database are assimilated.”

He went on to make predictions that seem very at home in our modern world.

“One polarity represents innovative stationary computers such as those which will be built into the wall. The other polarity will be the personified computers (AI), which will start to develop at a rapidly accelerating pace.”

In other words, smart homes and AI companions.

Takatori also had an idea for a “portable, yet not necessarily mobile personal computer without keyboards and monitors.”

This was nearly three decades before smartphones eliminated physical keyboards, and four decades before voice-first AI assistants became mainstream. He was clear about the emotional dimension too.

“Unless a computer has personified features like greeting the user with sincere feelings, it shouldn’t be called an educational device,” he said.

Japan’s parallel future

While Takatori explored intuition and AI, Japan’s broader computing ecosystem was racing ahead on a different path. Besher’s reporting captured a Tokyo overflowing with experimental hardware: MSX TV sets that doubled as computers, plum-colored machines sold with cartridges, and NEC’s PC-100, an advanced, Lisa-inspired system that reportedly unsettled Steve Jobs during a pre-Macintosh visit.

“He came, he saw, and he shuddered,” Besher wrote.

Takatori watched these developments from a distance, deliberately avoiding the MSX vs. CP/M standards war, calling it a “regression from the Renaissance to the Middle Ages in terms of software technologies.”

He viewed standards battles as distractions from deeper shifts in how humans would eventually, decades in the future, interact with machines.

A world catching up

Personified computers are what we now call AI assistants. Portable computers without keyboards are smartphones and wearables. Computers built into walls are smart homes and ambient displays.

Takatori didn’t predict these futures by extrapolating specs or roadmaps. He imagined them by “becoming” something else entirely: a dog, a dolphin, an observer outside the human frame.

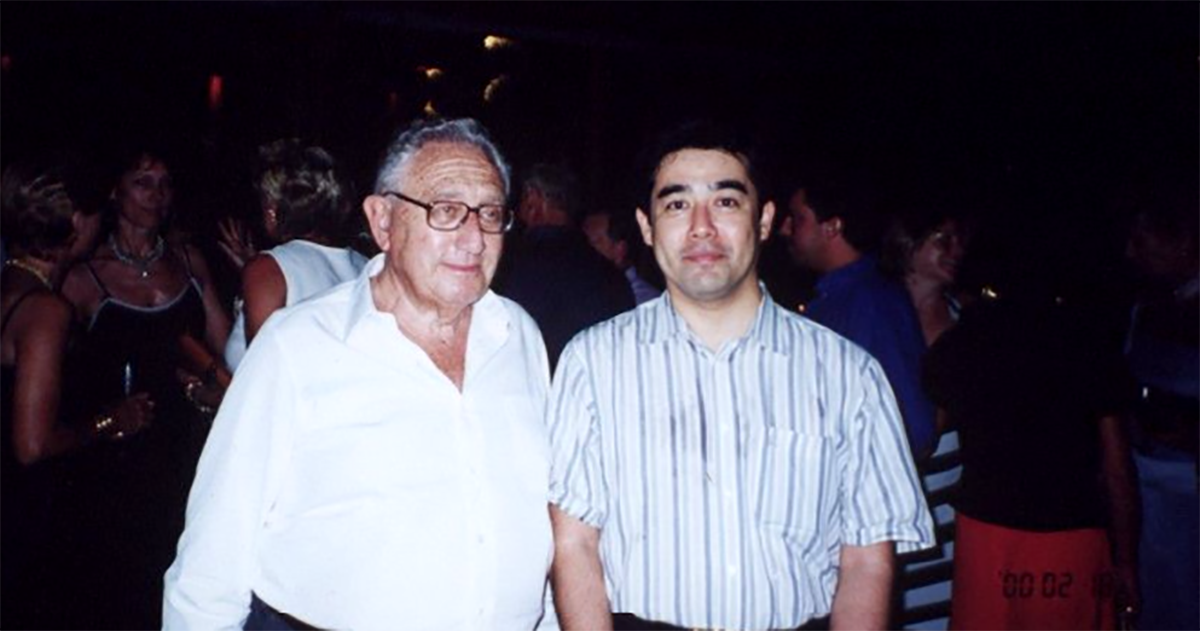

In the years following the InfoWorld article, Takatori met American diplomat and political scientist Henry Kissinger, as shown in the photo at the very top. He also went on to found Yozan Inc., a Tokyo-based mobile technology venture, which promoted its WiMAX wireless broadband in Japanese television advertising, as shown above.

He also filed an impressive number of technology patents, with his final ones (up until 2012) focused on wireless networking, transaction security, and adaptive authentication systems.

Whether the same “sixth sense” Takatori spoke about in 1984 was behind these later inventions is impossible to know, but the throughline between his early ideas about personified computing and his later work in mobile and networked systems is difficult to ignore.

Follow TechRadar on Google News and add us as a preferred source to get our expert news, reviews, and opinion in your feeds. Make sure to click the Follow button!

And of course you can also follow TechRadar on TikTok for news, reviews, unboxings in video form, and get regular updates from us on WhatsApp too.

Wayne Williams is a freelancer writing news for TechRadar Pro. He has been writing about computers, technology, and the web for 30 years. In that time he wrote for most of the UK’s PC magazines, and launched, edited and published a number of them too.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.