The codec landscape is changing, with six new codecs coming by the end of 2021. At the start of 2020, most streaming video producers encoded exclusively with the H.264 codec, which debuted in 2003. Some larger publishers like Netflix, Amazon, YouTube, and Facebook, also deployed H.264’s standards-based successor, the HEVC codec, and/or Google’s VP9 codec. A sprinkling of producers experimented with the Alliance for Open Media’s AV1 codec. Beyond these four existing codecs, in 2020, MPEG will launch three new codecs, Versatile Video Coding (VVC), Essential Video Coding (EVC), and Low Complexity Enhancement Video Coding (LCEVC).

With six new codecs to consider by the end of 2021, it’s worth reviewing factors that contribute to a codec’s successful adoption. In this article, I’ll review those factors using H.264 and HEVC, and create an analysis framework I’ll use in future articles to handicap the potential success for AV1 and the three new MPEG codecs.

Note that I’ll primarily be writing from the publisher perspective; not from the perspective of the player or encoder vendor.

- Understanding low-latency streaming solutions

- Best PTZ cameras, capture, and streaming devices

1. What’s the codec’s comparative efficiency?

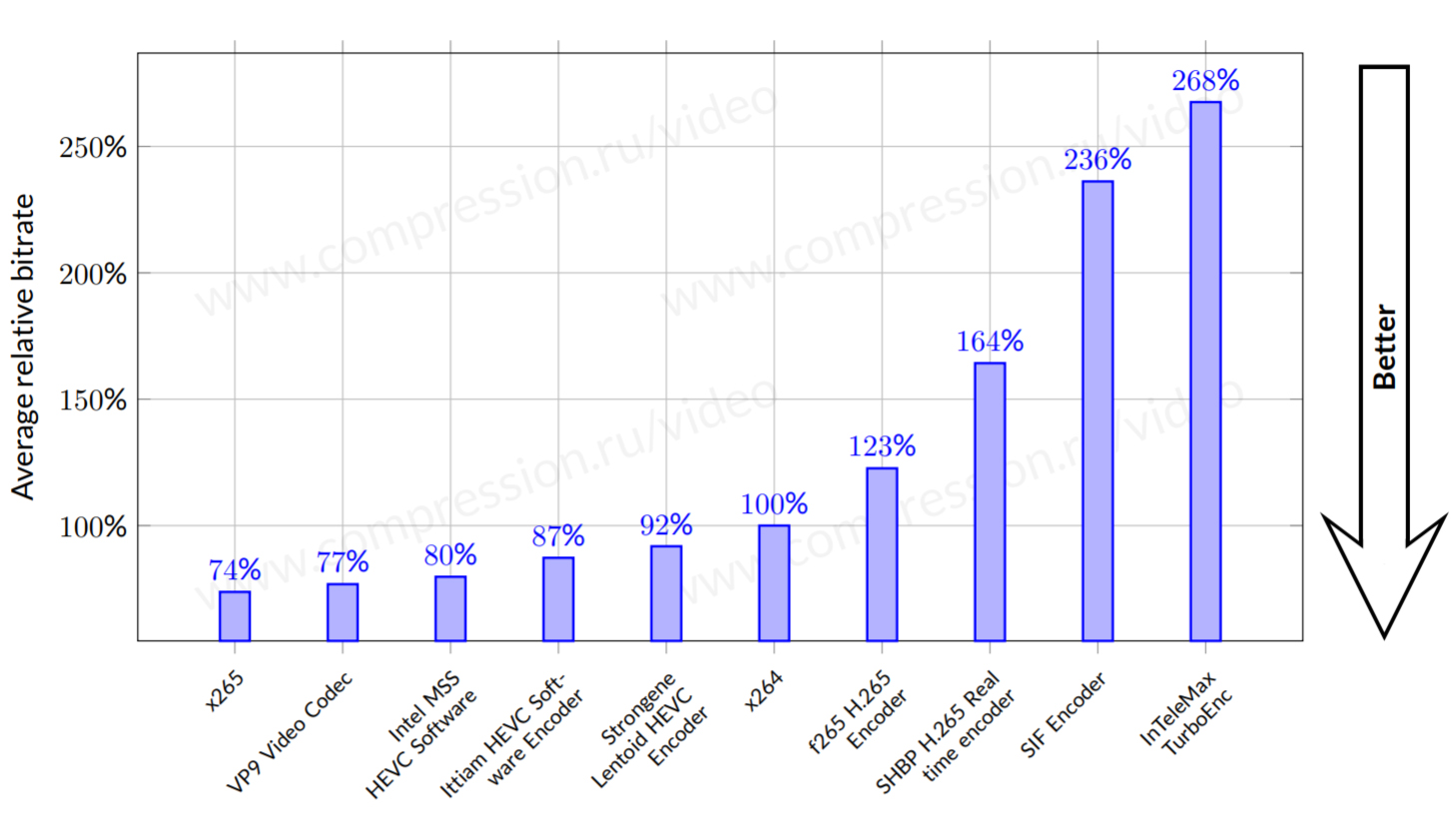

A codec’s most essential role is to reduce the size of the stream required to deliver video to our viewers. In many instances, efficiency is measured against H.264. You see this in Figure 1, from the 2015 HEVC Comparison report from Moscow State University (MSU). By way of explanation, MSU always presents its data using x264, one of several H.264 codecs, at 100% quality. Then, for each other codec, it shows the percentage reduction or increase in data rate necessary to produce the same quality as x264.

For example, in the chart, the x265 codec can deliver the same quality as x264 at 74% of the bitrate, or a savings of approximately 26%. The VP9 codec is not that far behind, at 77%, or a savings of about 23% over x264.

This savings represents one primary monetary benefit delivered by the newer codecs. Implementing x265 back in 2015 would have cut bandwidth costs for delivery of equal quality video to HEVC capable players by 26%. VP9 would have cut bandwidth costs by 23%.

Think of codec adaption as a break-even analysis. There are two sources of inflows; savings for delivery to existing customers, which we just covered, and additional revenue to customers in new markets, which I’ll cover in the next section. There are multiple costs associated with codec implementations. You’ll be delivering H.264 encoded video for the foreseeable future, so encoding and storage costs for the new codecs are both additive. You’ll also have to update your player and perform some measure of testing and QC.

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

Bandwidth savings obviously relate to the number of viewers for each video. Here’s a simple example. Assume it cost $20.00 to encode to an HEVC encoding ladder, and that you saved $0.01 in bandwidth costs per viewer. Once 2,000 viewers watch the video, you’ve made up that cost. If 2 million viewers watch the video, you’ve saved $20,000 in bandwidth costs. That’s why it’s easier for large companies like Netflix, YouTube, Amazon, and Facebook to deploy new codes.

Irrespective of size, when the savings or new revenue associated with the new codec exceed implementation and other costs, it makes financial sense to deploy a new codec. Obviously, the greater the compression efficiency over the existing solution, the greater the bandwidth savings.

All this aside, the vast majority of new codec deployments are not to harvest bandwidth savings or other delivery efficiencies. Only tip of the pyramid publishers like Netflix, Facebook, and YouTube have deployed VP9, despite it currently being about 35-40% more efficient than x264. Rather, publishers typically adopt new codecs like HEVC because it opens markets for new customers.

This leads to the next question.

Audio + Video + IT. Our editors are experts in integrating audio/video and IT. Get daily insights, news, and professional networking. Subscribe to Pro AV Today.

2. What new markets or platforms does the codec enable?

When Adobe added H.264 playback to Flash in 2007, H.264 was only about 15% more efficient than the VP6 codec, which was the most widely used Flash codec before H.264. Despite these meager savings, why did most publishers convert over to H.264 quickly and completely? Because while VP6 didn’t play on iPods, iPhones, or other mobile devices, H.264 did. With H.264 in both Flash and the predominant codec on mobile devices, publishers could drop VP6 and reach two markets with a single codec, a total no-brainer.

Similarly, most publishers have deployed HEVC to deliver 4K and/or high dynamic range (HDR) videos to smart TVs, set-top boxes, and OTT devices. For example, in their 2019 Global Media Format Report, which reported on their 2018 production, encoding.com reported that “we anticipate a very substantive increase in volume in 2019 driven by UHD HDR content as both premium HDR standards Dolby Vision and HDR+ map to the HEVC video format.” Unfortunately, encoding.com hasn’t updated that report for 2019 results.

Similarly, at long last, Apple started supporting either VP9 or AV1 on their 4K AppleTV devices so that their viewers could watch 4K videos on YouTube. This presages the importance that Alliance for Open Media vendors like Facebook, Netflix, YouTube, and Amazon will have on AV1 adoption.

The bottom line is that if the codec doesn’t enable any new markets, bandwidth savings are the only benefit. As stated, for whatever reason, outside of the largest video publishers, few others have found these savings sufficient motivation to deploy new codecs.

3. How is encoding time?

We’ve talked about the breakeven analysis. I ask this question because encoding time translates directly to encoding cost and the higher the cost, the harder it is to achieve breakeven.

As an example, AWS Elemental MediaConvert charges $0.024 per-minute for H.264 encoding, $0.048 per-minute for HEVC encoding, and $0.864 per minute for AV1 encoding. Fortunately, AV1 encoding times have dropped very significantly over the last few months and I’m sure Elemental pricing will follow. Still, when encoding times are as glacial as AV1s used to be, you need millions of views to accumulate the bandwidth savings necessary to achieve breakeven.

4. Can it be implemented in software on relevant platforms?

This question speaks to how quickly a codec can be implemented on platforms relevant to your service. Back in 2007, when Adobe added H.264 to Flash, playback was nearly universal on all computers and mobile devices. In contrast, with HEVC, hardware support on mobile devices was necessary for battery-efficient playback, and dedicated HEVC decoding hardware was necessary on most smart TVs, set-top boxes, and OTT devices.

Over time, more and more devices started supporting HEVC, and now it’s nearly ubiquitous in current generation products, with VP9 only slightly behind. But new codecs that require hardware for efficient playback are starting from scratch.

As a rule of thumb, it takes about two years for the first consumer devices with hardware support to appear. As a case in point, the AV1 specification was finalized in mid-2018, and the first smart TVs with AV1 support shipped in mid-2020. Obviously, it doesn’t matter how efficient a codec is when launched; it only becomes relevant when playback is available on a substantial number of platforms that you deliver to.

Which leads to the next question.

5. Does the Alliance for Open Media support the codec?

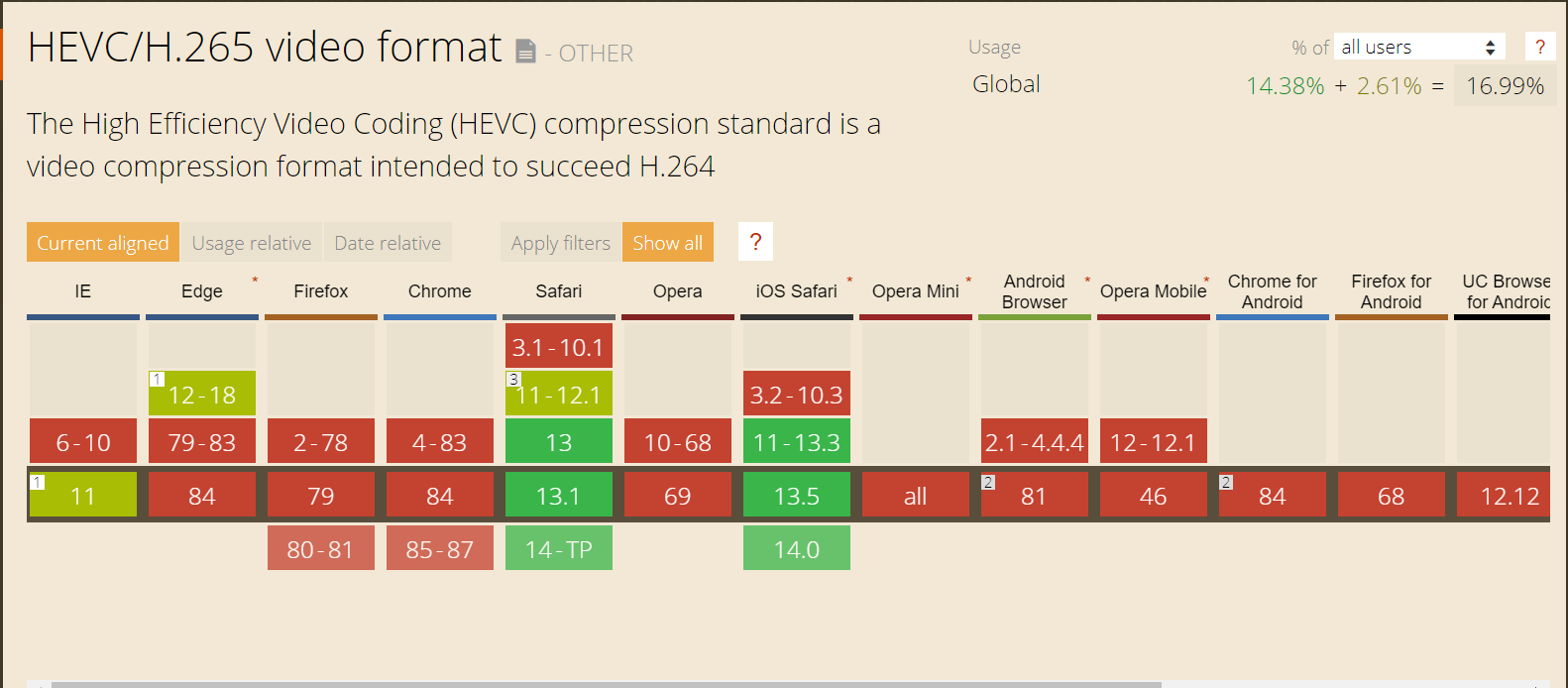

While it takes two years for hardware support, if playback requirements are modest, playback in a browser or mobile operating system can take a matter of weeks. However, Alliance for Open Media members Microsoft, Google, Mozilla, and Apple control most browsers and operating systems, and the formats that they support. This is why a full seven years after its launch, HEVC is only supported in 16.99% of all browsers and mobile operating systems tracked by www.caniuse.com (Figure 2).

The comparable number for AV1, which was launched five years later? 36.56%. What about VP9, which was launched around the same time as HEVC? 94.52%.

If a substantial number of your viewers watch on browsers and mobile devices, platform support makes a huge difference in the economics. This is particularly true because software support can be achieved so quickly.

At this point, it seems unlikely that AOM members will support any MPEG codec, whether HEVC, VVC, EVC, or LCEVC. So, where standards-based codecs like H.264 and MPEG-2 once had the upper hand, MPEG codecs are now at a distinct disadvantage in traditional computer and mobile markets.

6. Is the codec a MPEG standard?

The Motion Pictures Experts Group, or MPEG, created and promoted multiple audio and video codecs that helped transition analog video to digital. At one point, MPEG standards like MPEG-2 and H.264 had much clearer paths to success than proprietary codecs like VP9. Today, that dynamic has changed, so while the standardization process provides credibility to certain technologies, it’s not a guarantee of success?

What’s changed? Almost everything. Back when H.264 launched in 2003, broadcast was king, and streaming wasn’t the tail of the dog, it was a fingernail. Now, streaming is clearly the dog, and broadcast the tail, and companies that control codec deployment in browsers and mobile OSs, and content companies like Netflix and YouTube, have an incredible influence on codec deployment.

As I’ll talk about more in moment, with MPEG-2 and H.264, there was a clear and cohesive royalty policy, which went out the window with HEVC, which has three patent pools. Two of the pools have published rates and the annual caps jump from around $10 million for H.264 to over $60 million for HEVC. The other pool doesn’t publish its rates, and more than seven years after HEVC’s release, still hasn’t stated whether they will charge for royalties on content.

Mindful of the two-year development cycle for codec deployments, many hardware companies decided to deploy H.264 and HEVC before the royalty policy was clear. Post HEVC, large companies like Apple and Samsung may delay technology adoption until the royalty picture is clearer, which could add another 24 months to the adoption cycle.

Finally, from a video codec perspective, MPEG has contracted from about a ten-year cycle between MPEG-2, H.264, and HEVC, to a seven-year cycle for three additional video codecs to be finalized in 2020. Certainly, each codec offers a different range of features, performance, and other characteristics, and it’s unlikely that all will achieve the same commercial adoption.

7. What’s the technology ownership and monetization model?

Most codecs are the result of a collaboration between multiple parties. With some codecs, this results in one or more patent pools to allow companies to recoup the costs of their R&D investments. In contrast, VP9 was developed exclusively by Google while AV1 was developed by the Alliance for Open Media companies who all contributed their patents to AOM on a royalty-free basis.

However, just because a company or an organization claims to own all rights to a technology doesn’t make it so. Though Google claims that VP9 is open-source, as does the Alliance for Open Media for AV1, patent pool administrator Sisvel has launched patent pools for both VP9 and AV1, stating that these codecs utilize inventions covered by patent owners in their pools (note that the author consults with Sisvel regarding these pools).

Of course, both H.264 and HEVC are royalty-bearing for both encoders and decoders and some content-types, so the mere existence of a royalty doesn’t doom a technology. Rather, potential licensors care about the cohesiveness of that group, the clarity of their licensing terms, and how quickly they are available.

8. How set is the royalty structure?

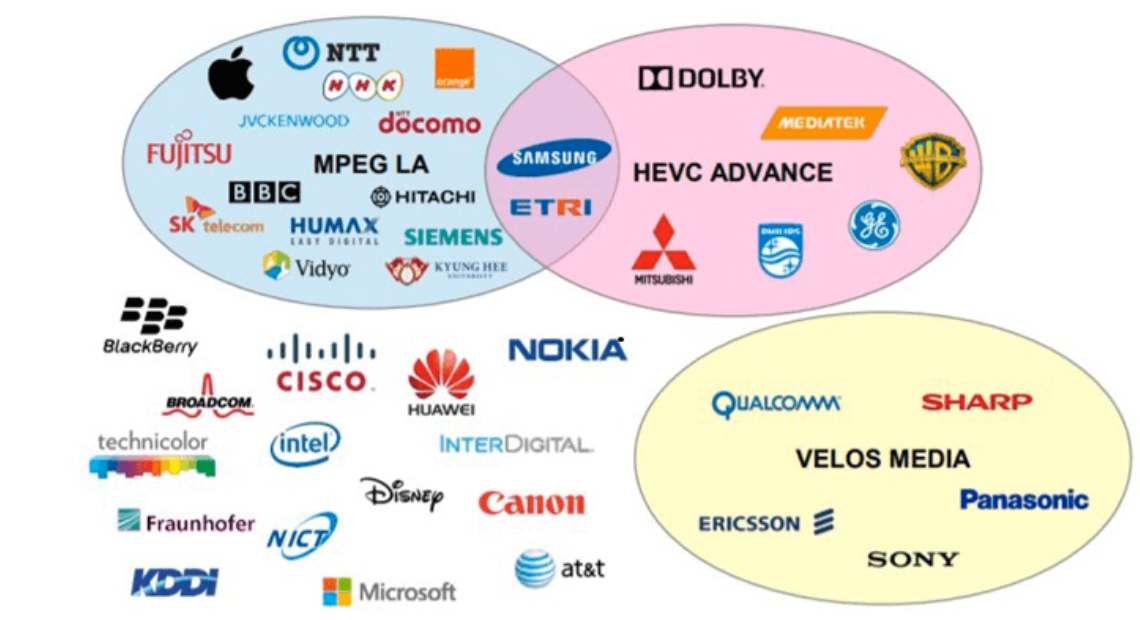

In 2017, Jonathan Samuelsson, CEO of codec developer Divideon, created the graphic shown in Figure 3, which became the poster child for the dysfunctionality represented by owners of HEVC-related patents. You see the three pools, and multiple additional companies, some very significant, not in any pool. Note that this is the original graphic designed by Samuelsson; the ownership picture has changed somewhat since then.

Clearly, if you’re a potential licensor, you’d prefer a single pool that included all known technology contributors, which actually could happen for EVC and LCEVC. That said, most major standards have more than one pool; what licensors want is a timely and known structure for all major contributors. Significantly, though the VVC standard finalized in July 2020, it’s unlikely that licensing terms will be known until mid-2021. If they look anything like what you see in Figure 3, VVC may never make it off the ground.

9. Is there a content royalty?

If you’re a streaming publisher, questions 4-8 dictate how quickly a codec might be adopted by hardware and software developers, which controls how quickly you can start using the codec to deliver to your viewers. This question determines how much it will cost you as a streaming publisher to deploy content with that codec.

Again, content royalties are not unheard of and don’t doom a codec to failure; both HEVC and H.264 have some content royalties. Obviously, however, these costs need to be inserted into the breakeven model to determine when and if it makes economic sense to deploy the new codec.

Looking Backward and Forward

Looking back, it’s easy to see why H.264 was (is) such a success: it offered modest bandwidth savings but played on computers immediately thanks to Flash, and offered entry into a new market (mobile). Licensing was controlled by a single patent pool that held a majority of the associated patents, and though hardware playback was required for H.264 playback on mobile devices, hardware support was near-universal to start with and soon became ubiquitous.

In contrast, HEVC debuted with a very disjointed licensing structure which discouraged technology adoption. Though HEVC support is near-universal on mobile devices, Smart TVs, and the latest generations of OTT devices, the lack of browser support reduces the overall return on investment, while the lack of clarity about content royalties is a huge concern for many publishers. As a result, HEVC has been implemented primarily by publishers distributing 4K and HDR videos to the living room.