What do Oculus Quest 2 game developers want from next-gen VR headsets?

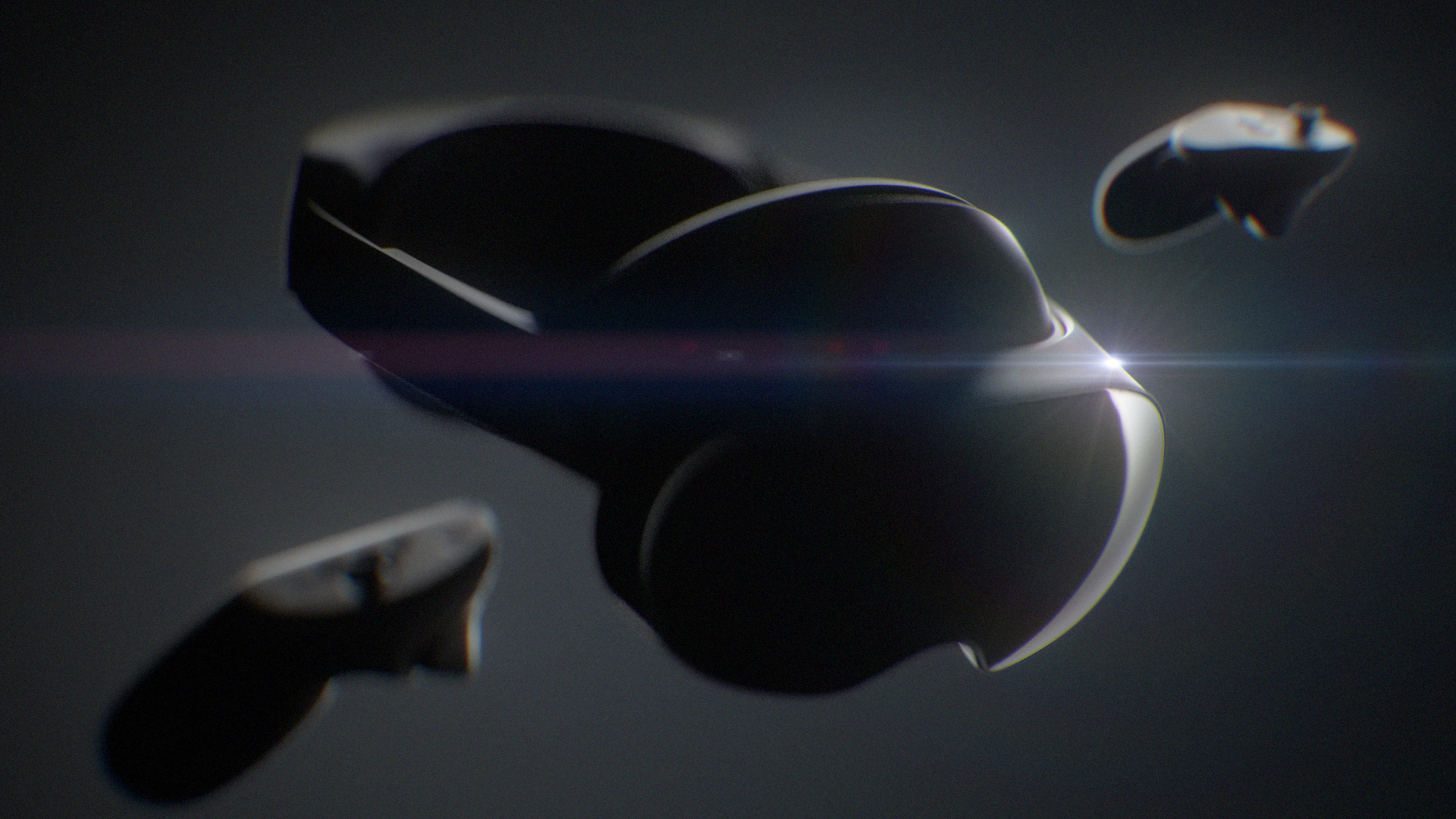

What are Project Cambria and PSVR 2 bringing to the table?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

While VR only seems to have properly taken off in the past couple of years thanks to Meta’s hugely popular Quest 2 headset, many of us are already thinking about what next-gen headsets have in store for us.

Meta itself is launching a successor to the Oculus Quest 2 this year with its Project Cambria device and Sony has unveiled its plans for a PlayStation VR 2 headset. Then there are new comments to the VR scene (at least in the US) like ByteDance’s Pico 4.

All of these next-gen VR headsets are boasting various improvements over what’s come before. Gamers will likely be delighted by the chance to experience VR games with higher-resolution displays and improved performance over what's been possible from standalone devices before, but what excites the developers behind the best VR games?

To answer this question we spoke to Polyarc’s Design Director Josh Stiksma and Publishing Director Lincoln Davis, some of the people that helped bring Moss: Book 2 – a beautiful VR fairytale – to the Quest 2 and PlayStation VR.

Eye spy

From a development and design standpoint, there was one innovation that Stiksma couldn’t wait for his team to get their hands on eye-tracking.

A major downside of standalone headsets is that their power is pretty limited compared with VR devices that rely on external processing power – like PC VR headsets. However, cramming in more RAM and more powerful chips isn’t easy if you want to keep the headset’s cost and weight under control.

At the same time, VR games require double the rendering power of a normal game as they’re creating a separate image for each eye. Eye-tracking could alleviate the problems by introducing improved foveated rendering.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Foveated rending is a fairly common process in gaming nowadays. Simply put this process allows games to only load in what the player can see. Putty much everything that would be off-screen either ceases to exist until the camera is turned to face it, or is loaded in using simpler textures and shapes to reduce how much processing power is wasted on stuff the player can’t interact with.

Using eye-tracking foveated rendering could be taken up a notch by only loading in what the player is looking at in real-time.

“Thanks to eye-tracking we'd know what you’re looking at and, importantly, what objects are at the edge of your vision,” Stiksma said. “We could then reduce how much processing power those objects eat up and instead use it to amp up the visuals of what you can see.”

But while these kinds of creative innovations have Polyarc excited for what next-gen hardware will bring, their other big request was a hope that headset creators will think a bit more inside the box.

The same, but different

Even as it exists right now – in its somewhat fledgling state – the VR space plays host to an incredibly diverse set of headsets. There’s the Valve Index and PlayStation VR that require external hardware like a PC or PS4 Pro to be able to function, and there’s the Oculus Quest 2 that instead relies on its own internal processors to power experiences.

Some headsets use just one handset while others rely on two, with each controller implementing buttons and/or touchpads in different places. Certain devices come with internal tracking of the headset and its controllers, while others rely on towers or an external camera – each option comes with its own unique benefits and limitations. And there are plenty of other factors to consider.

By comparison, more traditional game consoles are basically identical. Sure the Xbox Series X and PS5 have a few aspects that differentiate them but broadly they’re pretty similar in terms of the quality of games they can deliver and how players can interact with the digital world.

As Polyarc’s team explained, VR’s hardware diversity comes as both a blessing and a curse.

Stiksma compared VR headsets to Nintendo consoles, “everyone’s trying to think outside the box. Just like Nintendo and its Wii we’re seeing some really creative ideas in the VR space, but it can also make development a challenge.”

Polyarc like a lot of VR studios isn’t that big, their site’s team page lists 33 names – one of whom is the cute digital critter Quill from their game Moss. Meanwhile a studio like Xbox’s Playground Games – the team behind Forza Horizon 5 and the upcoming Fable 4 – has over ten times that amount according to the company’s LinkedIn page.

Because of its small team size and the massive differences between PSVR and the Oculus Quest 2, Polyarc decided to launch Moss: Book 2 on one platform at a time. This meant that it could focus on ensuring the game worked as well as it could on each system without sacrificing its scope. However, it also meant that Meta’s players were left waiting a little longer than those on Sony’s rival hardware.

As platforms start to coalesce the development time dedicated to each one will shrink, allowing studios to have multi-platform launches on the same date. But at the same time, Polyarc hopes to see headsets manufacturers continue to create unique options

“We see what Sony is talking about with its next headset, with all these new haptics that should boost immersion, and Meta with their Cambria headset and face tracking for better social experiences, and we’re excited to see what we and others can do with these features,” Stiskma explained.

“Only by trying out new ideas will we find what works and makes VR as good as it can be.”

You get a VR headset, and you get a VR headset

But a platform needs more than innovation to succeed, and Polyarc knows this. It also needs players. Because of this both Davis and Stiksma believed that next-gen VR headsets need to be accessible.

From a design perspective, that means slimming down the headsets. This could be using pancake lenses – a thinner style of lens than what’s currently used – and smaller processing units. This would allow younger audiences to enjoy VR – which is already starting to offer incredible entertainment and educational games that would be perfect for kids.

Then software-wise you’re looking at better passthrough filters.

“As a parent,” Davis said, “you really need to know what’s going around you sometimes. If my five-year-old comes running past it would be great to have the VR world automatically turn off or something like that so I can see them and we don’t bump into each other.

“The same is true with pets. With better filters or a button to quickly turn it on and off, you can stay aware of what’s around you while also enjoying the immersion of VR.”

Then finally there’s the price.

Both Lincoln and Davis echoed sentiments that the Quest 2’s price was the key to its huge success. Not only because it’s cheaper in and of itself, but also because you don’t need to then buy a console or PC to power it. This also makes the tech super easy to explain to someone.

In the old days of the Oculus Rift, you’d need to make sure you had a computer with certain minimum specs, making VR inaccessible to someone who wasn’t a computer boffin. Nowadays you can just pick up a Quest 2 and start playing.

Hopefully, next-gen VR headsets will find a way to keep VR as accessible as it is today, though with the Oculus Quest 2 recently getting a price hike it's unclear if future headsets will ever again be as affordable as Meta's flagship used to be. We'll just have to see what the next generation of VR has brings when it finally launches.

Hamish is a Senior Staff Writer for TechRadar and you’ll see his name appearing on articles across nearly every topic on the site from smart home deals to speaker reviews to graphics card news and everything in between. He uses his broad range of knowledge to help explain the latest gadgets and if they’re a must-buy or a fad fueled by hype. Though his specialty is writing about everything going on in the world of virtual reality and augmented reality.