Nvidia's new tech is a poor imitation of true ray tracing

It sells GPUs and promises next-gen visuals - but can we even agree on what ray tracing is?

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There’s a new feature in Nvidia’s GeForce Experience that I’m surprisingly excited about: SSRTGI (or screen space ray-traced global illumination to its friends). Enable it within Nvidia Freestyle, and with the click of a mouse, you’re inviting the bleeding-edge lighting tech into a long list of games that don’t formally support it, including Skyrim, The Witcher 3, and, oddly enough, Gwent.

As you’ll remember from literally everything Nvidia has said from about 2018 to the present, ray tracing is the global illumination method used by movie CGI effects houses for decades. It simulates how every light source in a scene behaves, everything it reflects and refracts off, and how different light sources interact. It literally traces rays of light from sources to all surfaces.

And that makes scenes look much more believable than traditional video game techniques. If you haven’t played ray tracing-compatible games, you've probably seen a few demos like the one below, showing realistic reflections in car mirrors, puddles, and other shiny things.

So for Nvidia to offer an effect with ‘ray tracing’ in the title, for free, in a bunch of games that don’t natively support it feels a bit like discovering Napster for the first time – some kind of crazy jailbreak for a desirable tech.

Worried about ray

If that sounds a bit too good to be true, given that ray-traced games usually need engine-level implementation like Remedy’s underappreciated Control or the Quake II RTX release, or require you to sign up to somebody’s Patreon for the pleasure of adding it to Minecraft or GTA V, well – it kind of is. Because not all ray tracing is born equal.

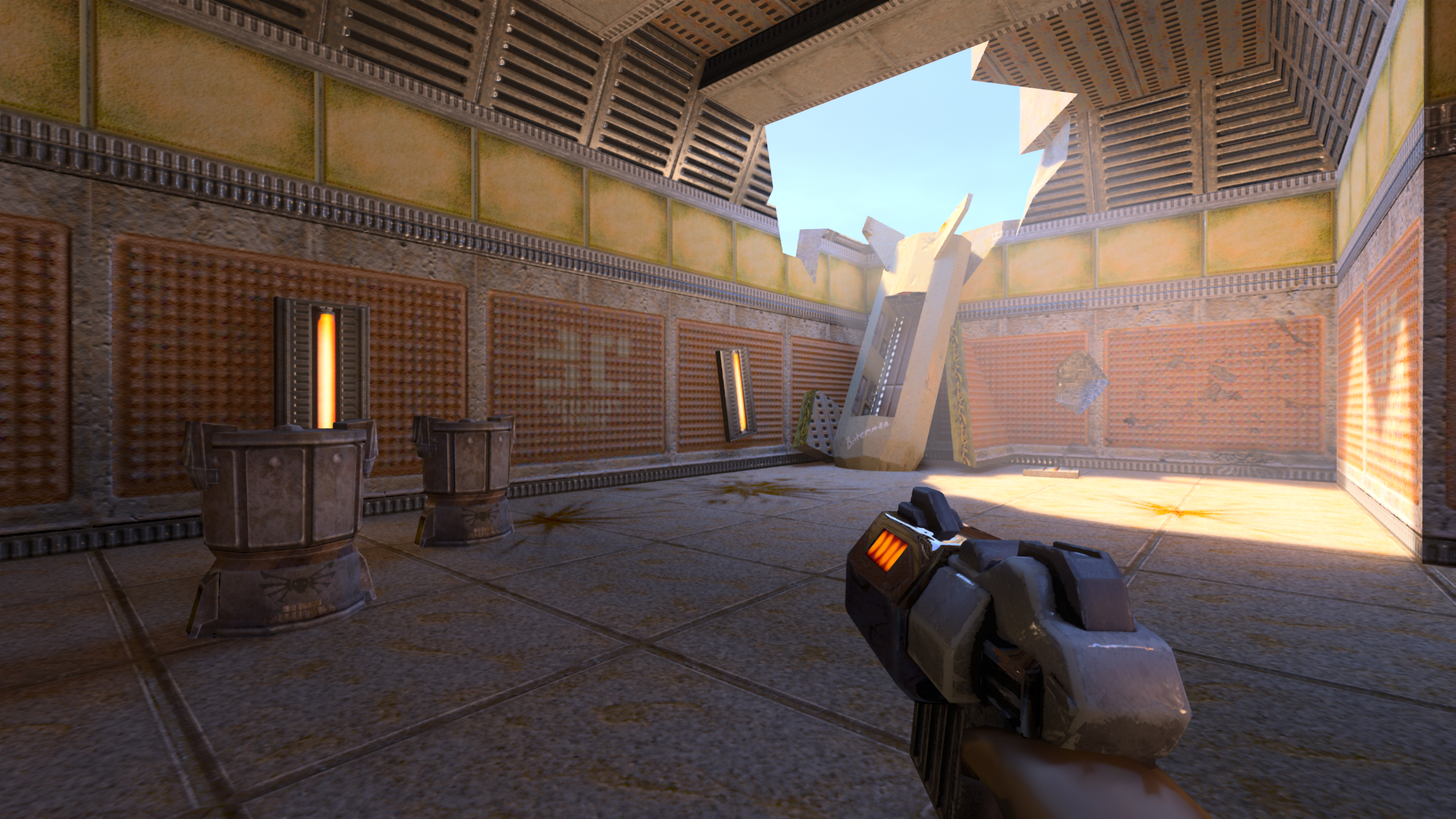

In its highest fidelity and most engine-integrated form, ray tracing transforms many elements of the scene in front of you, including reflections and the way light diffuses and refracts off surfaces. We might not all recognize what’s happening on a technical level or how, but generally, we look at something like Quake II RTX and go: "That looks quite a lot better now."

That kind of ray tracing implementation usually requires the game engine to inject the ray tracing. It has access to all the information about a scene – where the surfaces are and what they’re made of.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

And that’s different from SSRTGI, the new quick 'n' dirty effect in Nvidia’s suite. The clue’s in the title here: ‘screen space’. Instead of simulating the path of every possible light source in a scene, SSRTGI only worries about the bits the player can see. The benefit of that approach, like all screen space effects, is that it’s much less resource-hungry than a global version. And, after all, what’s the point of spending GPU grunt power rendering things you can’t see?

While there’s usually wisdom in the efficient approach, in the case of ray tracing, cost saving isn’t really an option: the complex subtlety of light’s behavior defines the technology. The effect is lost if you don’t capture the secondary and tertiary bounces off surface after surface. Without it, you’re left with a visibly less impressive image.

You’ll see this for yourself if you mess around with SSRTGI. I don’t know about you, but my Skyrim and Witcher 3 installs are already so modded that they’re barely recognizable. The retextures and reshade presets achieve much of the visual legwork before adding any ray tracing. Maybe that’s why neither game looks transformed, the same way native RTX titles like Cyberpunk do, when you implement a bit of ray tracing. But probably, it’s about the limitations of that screen space effect.

Marching banned

Other important variables in that broad term, ‘ray tracing’, cause debate as to what it really is, too. The biggie is triangle intersection vs ray marching. The former is a more complex and accurate way of tracking a light beam’s journey across an environment as it pinballs off every hard surface and diffuses through every conveniently hung cloth. The latter is more of an approximation than a simulation, to the degree that some visual artists and graphics experts contest that it should even be considered ray tracing at all.

What does that mean for us, the gamers who just want to see our reflections in the odd puddle and feel like we’re getting our money’s worth for that £5,000 graphics card we spent three years on stock checker sites to find?

Personally, I think it means we’re in danger of being taken for a ride. We’re reaching a tipping point now – where enough of us engage with the term ‘ray tracing’ when we see it for games and manufacturers to use it whenever they can. It’s sort of a byword for ‘the next big thing in graphics’ – the PC gamer’s equivalent of the PS5's DualSense haptic control or Xbox Series X’s… um…

A light touch

But as we’re seeing, it’s not like the advent of 1080p visuals or 3D polygonal graphics. It’s not simply on or off – as our virtual worlds grow exponentially in complexity, the techniques and technologies used to build them are tougher to understand and define.

We should look at ray tracing as an art rather than a science. Even though the science involved is formidable and on the verge of incomprehensible to most of us, like so many 3D rendering techniques, it seems more about how developers use it than whether it’s simply present.

It's best that the implementation is left to the wisdom of art directors. Otherwise, we end up with years of triple-A titles in which it’s constantly raining and night-time in a city full of neon signs, just so that developers can show off that ray tracing is definitely happening.

Thank you, Nvidia, and thank you, Pascal Glicher, for your original SSRTGI shader; they’re great for experimenting with and customizing the look of many games. But let’s not get carried away thinking ray tracing is a switch we can flip to turn any game into something futuristic.

Ad creative by day, wandering mystic of 90s gaming folklore by moonlight, freelance contributor Phil started writing about games during the late Byzantine Empire era. Since then he’s picked up bylines for The Guardian, Rolling Stone, IGN, USA Today, Eurogamer, PC Gamer, VG247, Edge, Gazetta Dello Sport, Computerbild, Rock Paper Shotgun, Official PlayStation Magazine, Official Xbox Magaine, CVG, Games Master, TrustedReviews, Green Man Gaming, and a few others but he doesn’t want to bore you with too many. Won a GMA once.