Stray publisher “shadow drops” a classic indie game on Steam

Good laugh

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There’s almost nothing games haven’t let me control yet, whether that’s a cat, a fox, a dung beetle, several ghosts or a boy with cat ears. Yet something about Hohokum feels different – partly because I’m not sure what exactly I am in this game. Am I a worm? A dragon? I’m not really majestic enough for the latter; more like a colorful strand of spaghetti moving around a 2D environment. As it turns out, this mystery represents the first rule of Hohokum – it’s not really necessary to make sense of anything you see.

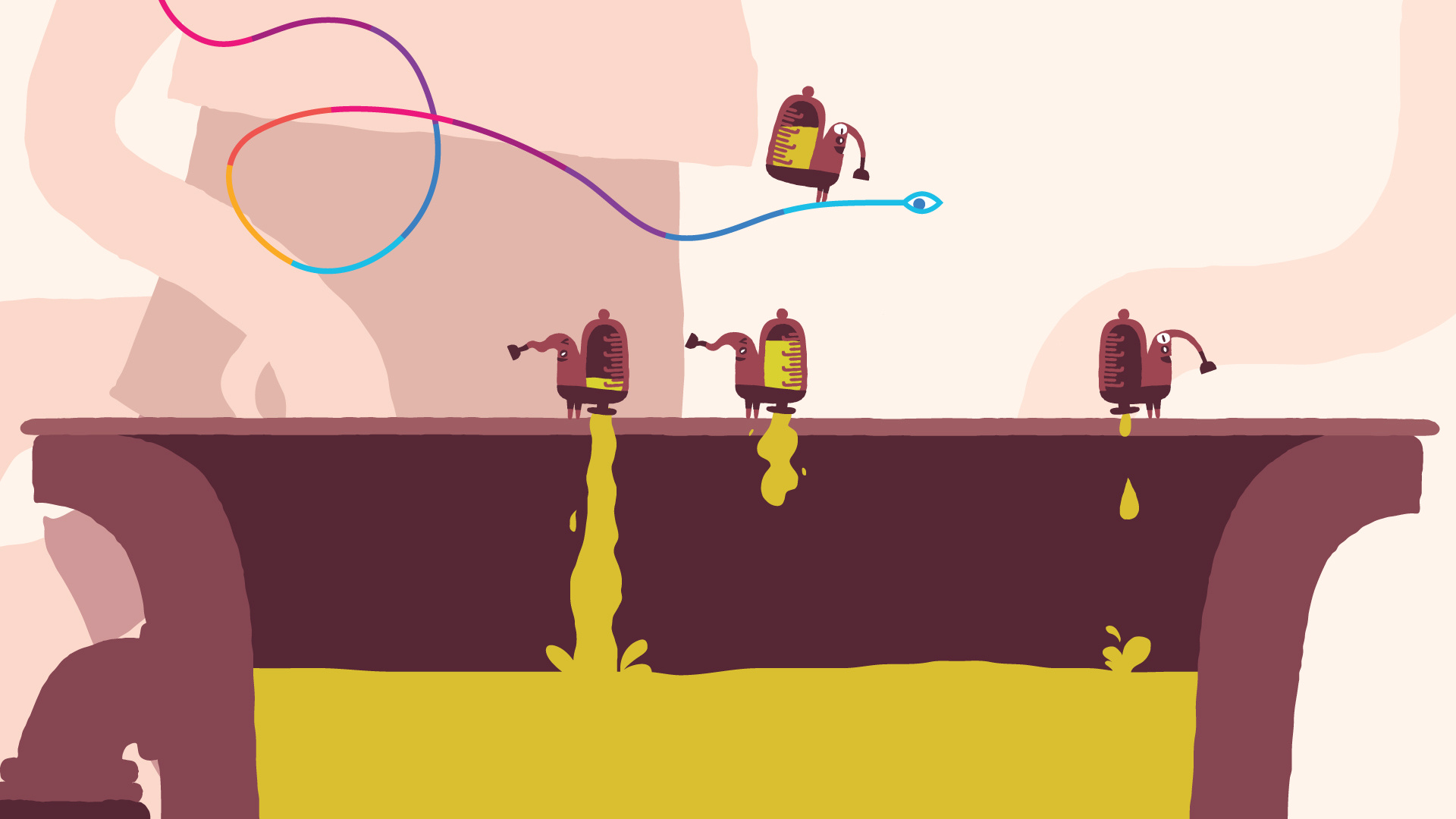

Hohokum originally released in 2014 for Playstation 4, Playstation 3 and the PS Vita, and is now available on PC thanks to Stray publisher Annapurna Interactive. It’s described simply as an “art game”. That description doesn’t exist to be pretentious, it just goes to show that some games don’t want to neatly fit into pre-existing genre categories. Hohokum is very much defined by its art, supplied by illustrator Richard Hogg. Left to his own devices, Hobb draws whimsical creatures that are never quite animal, never quite human, but always absolutely charming. Hohokum is essentially a game of turning these creatures into game mechanics, and vice versa.

The game doesn’t talk to you – if it is indeed a toy, it’s one without a manual, to be poked and prodded

Designer Ricky Haggett co-founded Hohokum’s developer Honeyslug, and now works with Hobb and his wife Nikki Haggett at studio Hollow Ponds. He says that, while he spent quite a lot of time explaining the game to audiences in 2014, there are now more like it. It seems that while the debate about whether games are art is still alive and well, the “art game” has found its place.

Toy story

Hohokum is less any particular type of genre experience and more like an interactive toy. You’re thrust into its world without explanation, feeling out the movement of your character and figuring out how you can affect the different worlds you visit. The game doesn’t talk to you – if it is indeed a toy, it’s one without a manual, to be poked and prodded, turned this way and that (literally, the dragon does the most enticing pirouettes in the air, very enjoyable).

“Hohokum feels like a real place which is unconcerned with whether you are making ‘progress’ or having a good time or whatever,” Haggett says. “Dick [Hogg] likes to say that it’s a bit like going on holiday somewhere you’ve never been before and don’t speak the language – probably you’re going to find some fantastic places, but also spend some time being a bit lost and confused; maybe even frustrated.”

For Haggett, that frustration is part of the experience, and while his design philosophy has slightly changed in this regard, he still thinks players can be left to their own devices much more often than many modern games allow them to. While Hollow Ponds’ follow-ups, Wilmot’s Warehouse and I Am Dead, thoroughly explain themselves, both preserve the feeling of freedom that is inherent in Hohokum – the idea that you can just muck around and see what happens next.

Distraction quest

In Hohokum, I have made flowers bloom and caused fireworks to set off. I served as a way of transport for tiny people. I’ve married tiny people in an unconventional ceremony. I’ve made my way through pipes and fairgrounds. Set to an immensely relaxing soundtrack, Hohokum is a celebration of color, movement and sound. What Haggett calls the game’s “uncompromising nature” can indeed be confusing at times, but only because nothing you’re able to do seems more or less likely than the next thing.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

“One of the challenges is that the game is full of things which are entirely incidental to making progress – they’re just toys or distractions,” Haggett explains. “These things are never made to look less interesting or important than the things which drive progress: because philosophically to us, they aren’t less important.”

It makes me feel as if I’ve stumbled into a foreign festival, one I get to participate in for a short while before I leave, ever so slightly dizzy

If Hohokum is a place, it’s one of creative anarchy. However, instead of frustrating me, it makes me feel as if I’ve stumbled into a foreign festival, one I get to participate in for a short while before I leave, ever so slightly dizzy.

Soho-kum

It also isn’t a long game, short on actual hours but rich in colors, characters and settings to play with. It does often feel like taking your time at an interactive exhibit, and according to Haggett, many design meetings between him and Hogg have taken place in museums.

To make something players can intuitively pick up requires a lot of testing, to find out what exactly feels natural to the broadest possible audience. Honeyslug wanted Hohokum to be a game people could share with their friends and families, including those who aren’t necessarily proficient with video games.

“Every week we would go to PlayStation’s offices in Soho, and test a couple of levels with someone who’d answered a callout on their local messageboard,” Haggett says. “This would involve watching them for an hour or so, and making pages and pages of notes, then going back and trying to figure out what we should change next.”

While each level in Hohokum does have an objective, reaching it is supposed to feel almost accidental – an organic result of playing around, rather a puzzle you have to think long and hard about. “Actually getting to that point was really hard though,” Haggett says. “A big thing we did lots of iteration on was the order that people would see the various elements in each place. There’s no text, but with subtle camera hints and audio you can definitely tune people into a kind of narrative.”

Anna 'nother thing

Eight years later, Hohokum has aged astoundingly well – not only because Hogg’s art style is timeless, but perhaps also because the game itself didn’t adhere to any particular design trends and trusted players to figure things out on their own. It’s certainly a game that fits into Annapurna Interactive’s modern-day catalog, and not only because Annapurna has published Haggett and Hogg’s subsequent games.

Wow, how did we manage to make all this stuff?

Ricky Haggett, designer

While it’s slightly different to what most people expect from the medium and can thus be considered niche, Hohokum brings people of many different kinds together, similar to other Annapurna-published games like the short and sweet Nintendo Switch game Sayonara Wild Hearts and donut hole puzzler Donut Country. Haggett is simply happy to see it reach a bigger audience, and to have it preserved in a way that can be difficult on consoles.

“I had barely played it since this PC version, and when I was playtesting, I was struck by how much of it there is,” he says. “So many different places, so much animation, lots of toys and mechanics and puzzles and music and sounds! I find myself wondering, ‘Wow, how did we manage to make all this stuff?’. I guess we were a bit younger!”

Malindy Hetfeld is a full-time freelance writer and translator specializing in game narrative, Japanese games, and, of course, music. You can find her work on Eurogamer.net, Unwinnable.com, Official Playstation Magazine and Techradar