Cyber-mercenary group Bahamut strikes again via fake Android VPN apps

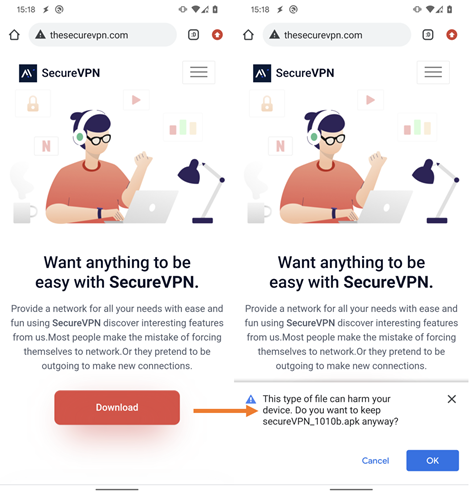

A malicious version of SecureVPN is the main vector of attacks

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

An infamous cyber-mercenary group is injecting Android devices with a spyware to steal users' conversations, new ESET research has found.

These malware attacks are launched via fake Android VPN apps, with evidence suggesting the hackers employed malicious versions of SecureVPN, SoftVPN and OpenVPN software.

Known as Bahamut ATP, the group is thought to be a service for hire that typically launches attacks through spear phishing messages and fake applications. According to previous reports, its hackers have been targeting both organizations and individuals across the Middle East and South Asia since 2016.

Estimated to have begun in January 2022, ESET researchers believe that the group's campaign of distributing malicious VPNs currently remains ongoing.

From phishing emails to fake VPNs

"The campaign appears to be highly targeted, as we see no instances in our telemetry data," said Lukáš Štefanko, the ESET researcher who first discovered the malware.

"Additionally, the app requests an activation key before the VPN and spyware functionality can be enabled. Both the activation key and website link are likely sent to targeted users."

Štefanko explains that, once the app is activated, Bahamut hackers can remotely control the spyware. This means that they are able to infiltrate and harvest a ton of users' sensitive data.

"The data exfiltration is done via the keylogging functionality of the malware, which misuses accessibility services," he said.

From SMS messages, call logs, device locations and any other details, to even encrypted messaging apps like WhatsApp, Telegram or Signal, these cybercriminals can spy on virtually anything they found on victims' devices without them knowing it.

ESET identified at least eight versions of these trojanaized VPN services, meaning that the campaign is well-maintained.

It is worth noting that in no instance was malicious software associated with the legitimate service, and none of the malware-infected apps were promoted on Google Play.

The initial distribution vector is still unknown, though. Looking back at how Bahamut ATP usually works, a malicious link could have been sent via email, social media or SMS.

What do we know about Bahamut APT?

Despite still being not clear who's behind, the Bahamut ATP seems to be a collective of mercenary hackers as their attacks don't really follow a specific political interest.

Bahamut has been prolifically conducting cyberespionage campaigns since 2016, mainly across the Middle East and South Asia.

The investigative journalism group Bellingcat was the one first exposing their operations in 2017, describing how both international and regional powers actively engaged in such surveillance operations.

"Bahamut is therefore notable as a vision of the future where modern communications has lowered barriers for smaller countries to conduct effective surveillance on domestic dissidents and to extend themselves beyond their borders," concluded Bellingcat at the time.

The group was then renamed Bahamut, after the giant fish floating in the Arabian Sea described in Jorge Luis Borges’ Book of Imaginary Beings.

More recently, another investigation highlighted how the Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) group is increasingly turning on mobile devices as a main target.

Cybersecurity firm Cyble first spotted this new trend last April, noting that the Bahamut group "plans their attack on the target, stays in the wild for a while, allows their attack to affect many individuals and organizations, and finally steals their data."

Also in this case, researchers stressed the cybercriminals' ability to develop such a well-designed phishing site to trick victims and gain their trust.

As Lukáš Štefanko confirmed for the fake Android apps incident: "The spyware code, and hence its functionality, is the same as in previous campaigns, including collecting data to be exfiltrated in a local database before sending it to the operators’ server, a tactic rarely seen in mobile cyberespionage apps."

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

Chiara is a multimedia journalist committed to covering stories to help promote the rights and denounce the abuses of the digital side of life – wherever cybersecurity, markets, and politics tangle up. She believes an open, uncensored, and private internet is a basic human need and wants to use her knowledge of VPNs to help readers take back control. She writes news, interviews, and analysis on data privacy, online censorship, digital rights, tech policies, and security software, with a special focus on VPNs, for TechRadar and TechRadar Pro. Got a story, tip-off, or something tech-interesting to say? Reach out to chiara.castro@futurenet.com