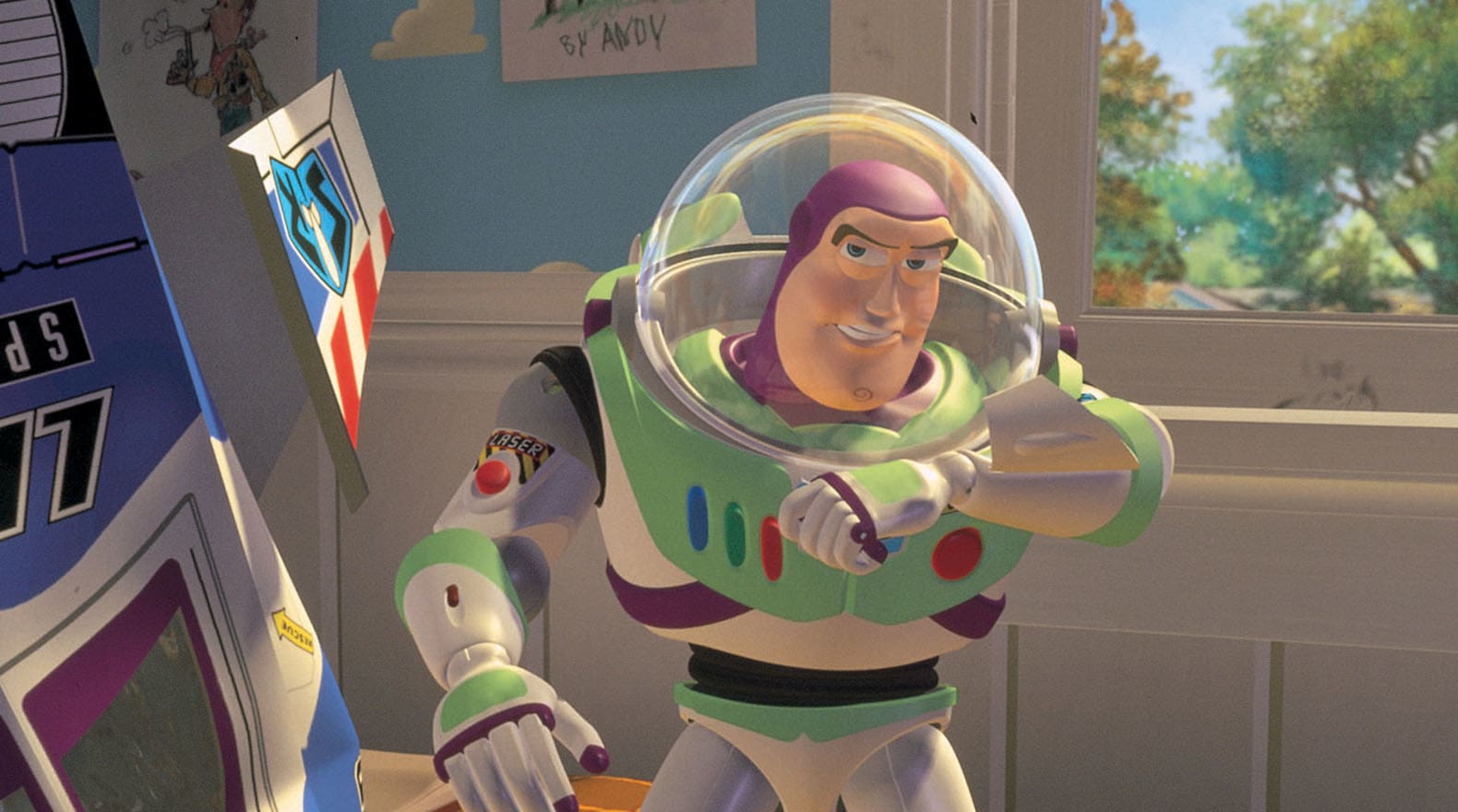

25 years of magic: A look at how the VFX industry has evolved since Toy Story debuted

1995 was the year when everything changed in the world of computer-based animation

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The year was 1995 and a movie called Toy Story had burst onto the scene, produced by Pixar Animation Studios and directed by John Lasseter. It was the first feature film entirely produced by computers and helped to push the technology into the limelight.

While ground-breaking, it’s worth remembering that Toy Story was rendered at only 1,536 x 922 pixels - that’s a third fewer pixels than a full HD (1080p) resolution and a fraction of what 4K can achieve.

Even then, the movie required 117 Sun Microsystems workstations to render each of the 114,000 frames of animation, which took up to 30 hours to render apiece.

- Here's our list of the best mobile workstations out there

- We've built a list of the best video editing computers around

- Check out our list of the best video editing laptops available

We caught up with Lon Molnar (Co-President) and Matt Panousis (Managing Director) of Monsters Aliens Robots Zombies (MARZ), a Toronto-based VFX studio as well as Penny Holton, Senior Lecturer in Animation at Teesside University in Middlesborough, United Kingdom, to discuss how technology has evolved since the first Toy Story landed a quarter of a century ago.

How difficult (or easy) would it be to produce something like the original Toy Story today?

LM: The first Toy Story was ground-breaking. Nothing like that had ever been done in the long form and once Pixar did it, it paved the way for others to follow the same processes and infrastructures. That alone means there would be massive efficiencies and a lot of helpful context for attempting a similar project now. For example, when almost a decade after Tory Story, Pixar did Wall-E, they started to look more at incorporating live-action cinematography in their animation.

On that project, the legendary Roger Deakins was called upon to help them with their lighting and lenses meaning that they adopted 100 years of filmmaking techniques into animation. This difference, too, would improve the quality of Toy Story if we attempted to create it now.

Since 1995, the visual effects and animation industries have changed so much (although I still consider them in their infancy) that many companies are creating that level of high-quality work reminiscent of Toy Story but actually doing it cost-effectively. They are pushing on the speed, cost and quality fronts.

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

For example, studios like Tangent Animation in Toronto are adopting Blender (a free 3D creation suite) as their backbone, and taking advantage of such open-source tools to then focus on talent and hardware.

In terms of hardware, a key difference is that we have great looking GPU rendering now, which Pixar didn’t have. The speed of GPU (which unlocks better quality and more iterations) would be exponentially faster. So the timeline could be much more condensed or at least give you so much more instant feedback, that you could rapidly improve the quality and have a lot of flexibility over the story as you work.

[Ed: It is worth remembering that the first GPU, the original GeForce 256, was launched in 1999, a full four years after the release of Toy Story. It had a processing power of about 50 GFLOPS. The Geforce RTX 3090, for comparison, is 70 times faster at 3,568 GFLOPS.]

Going through the pipeline differences between 1995 and today, we now have photorealistic lighting and environment maps - which you wouldn’t have back then. Today you have reflection maps, while back then you had to fake it. Simulations would have taken forever to create, light and render - today, out of the box simulations look fantastic. Back then, they were rendering right out of the 3D environment what you saw was what you got.

When you rendered an entire scene, if you needed to fix one aspect, you had to re-render again. Today, we use compositing tricks to find more efficient ways to get to the final look. We can render in pieces. If we want to fix the look of a kettle in the background, we don’t need to re-render the whole scene, we can just re-render the kettle. And lastly on the animation front, there was no real pipeline for bringing traditional animators into a CG environment. Now you have more traditional animators going back and forth, and artists out of school are learning the basic fundamental skills in a CG environment. That’s key.

PH: If you have a passion for animation it is now possible to create your own 3D work at home. Blender is a free, open source software and is a very good alternative to commercial apps such as Maya. However, to create work that is even comparable to Toy Story takes study and practice. Animation is like learning to swim, at first you are floundering and splashing about and you think you will never manage to even float, and you need to learn proper technique and put in many hours of practice.

Find a good teacher either by going to college and university (we offer undergraduate and postgraduate animation courses at Teesside University) or through online tutorials and, dare I say it, books. Becoming an animator or a visual effects artist is now more possible than it has ever been and there is a huge industry there for you if you want to make it your career. At the same time it is also an engaging, if mindbendingly, frustrating hobby.

How has the market evolved over the past two decades?

LM: The move to automation seems to be one of the largest overall trends, particularly in the last 5-10 years. This industry has gone from manually inputting individual vertex or pixel information via command prompts, to machine learning neural nets that require minimal user input to start and finish an entire effect. As a whole, software is always moving in the direction of liberating artists from "unartistic" or repetitive tasks, so that they can spend more time on making beautiful imagery.

As the hardware gets better, it enables the software to do more, which drives the software to demand more from the hardware and so on. Every few years, there is a novel game-changing piece of technology that pushes things in a new direction. This isn't unique to VFX - any industry that relies heavily on some form of heavy computation to produce something is in this cycle.

The VFX market is a truly global one now with companies in dozens of countries all over the world. Each local market is continually carving a piece of the pie out in some way, whether it be outsource vendors in India and Thailand or major hubs like L.A., London and Toronto. What enables all of this is the technology.

Before global broadband internet access, the logistics of sharing data between studios, vendors and freelancers outside of the same city was a logistical nightmare at times. Now for the most part, anything can be sent to anyone, anywhere. Though files and assets in the several TB range are still shipped on drive, I can't imagine that will be the case for too much longer.

It goes without saying that this interconnectedness means more collaboration and communication on a larger scale than ever before. For example, MARZ was founded as a Toronto-based studio and while that is still our home office, technology and COVID-19 have both pushed and freed us to bring on artists working in various cities, to collaborate on projects for clients all around the world. That would have been a much bigger feat just a few years ago.

PH: When Toy Story was released in 1995, creating computer imagery was an extremely difficult and eye-wateringly expensive business. Pixar was at the forefront of computer-generated imagery development and had the money, will and talent to take on the challenge of the first fully 3D feature film.

At the same time in the UK, the average cost of a computer capable of working in 3D was £50,000 and commercially available 3D software was a similar price, so this made any kind of large-scale production the domain of very few companies. At this time computers were a lot less powerful than they are today, which is why making a 3D feature or visual effects then was such an incredible ground-breaking achievement.

However, as time went by, computers became cheaper and much more powerful, and software became more sophisticated and able to harness the power and capability provided by new developments in computer technology. By 2000, making high-end 3D movies and effects was much more achievable and amazing work was being produced by a number of companies around the world. Today we are at the point where it is possible to create 3D visual effects imagery that is almost life-like and it is used in just about every film you see.

How do you see the VFX market evolving over the next few years?

MP: Key underlying technologies like machine learning and game engines are hitting inflection points and the implications for the future of VFX are significant. What we're seeing right now is the emergence of the Unreal Engine as a solution to plan and block out larger projects in advance and make on-set shoot days more efficient. With regards to Virtual Production and using Unreal as a solution to walk off the set with final shots and avoid the need for meaningful time in post-production, our conclusion is that there are too many logistical issues right now.

There are certain scenarios that lend themselves to Virtual Production (VP), but at MARZ, our focus is on technologies that enable efficiencies on a broad spectrum. Unreal 5 is a step in the right direction and as the cost of LED screens decrease over the years, that may open up opportunities to use VP on a broader scale. Our interest in Unreal is focused solely on using it for real-time rendering.

We feel machine learning has a much broader application and enables order of magnitude improvements in efficiency. The limitations of the technology is that it is still narrow, but for repeatable, more menial aspects of the VFX pipeline, the gains are massive; we don’t look at technology in a vacuum. The industry is shifting, TV is becoming the predominant medium for story-telling, and with TV comes not just a high bar for creativity, but condensed budgets and timelines. Within that context, machine learning is becoming a powerful way to increase speed and reduce cost without sacrificing the quality of the output. The same argument applies to real-time rendering. As for Virtual Production, we don't see how it makes much sense in the TV context outside of massive projects.

- Here's our list of the best cloud storage services right now

Désiré has been musing and writing about technology during a career spanning four decades. He dabbled in website builders and web hosting when DHTML and frames were in vogue and started narrating about the impact of technology on society just before the start of the Y2K hysteria at the turn of the last millennium.