How a new Dune video game could succeed where others have failed

The spice must flow on PC and consoles too

It’s been a long time coming but Warner Bros. and Legendary’s gigantic Dune adaptation finally hit cinemas and HBO Max this week, sparking a revival of interest in Frank Herbert’s beloved sci-fi franchise.

To mark the release of the latest adaptation of this sci-fi epic, we’re looking back at the history of Dune games in an effort to understand why the franchise hasn’t seen long-running success on gaming platforms, despite offering a rich and unique sci-fi world brimming with lore that should have developers rubbing their hands in glee, and how the Dune franchise could make a gaming comeback as grand as Frank Herbert’s books.

- Dune is an absorbing and visually striking sci-fi epic – with one major problem

A troubled history worth remembering

1992’s Dune, developed by Cryo Interactive and published by Virgin Games, was an ambitious mix of real-time strategy and interactive adventure, borrowing elements from hits such as The Secret of Monkey Island in order to flesh out both its characters and the dense world of Arrakis. Its development was as troubled as the production of David Lynch’s 1984 film, and the whole thing was almost canned several times.

However, the game was a success and proved there was a future for the IP in the gaming world. If we look back at the critical reception, most reviewers praised the blend of adventure and RTS, with some outlets praising how Cryo struck gold by focusing on what made Arrakis a unique setting and toying with the player’s agency. That type of approach sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

We’re more than used to flexible, non-linear storytelling in games by now, especially when it helps explore vast, unknown worlds. Dune is all about this – most of Herbert’s original novel spends almost half of its pages setting up Arrakis and its rules, plus other planets and a good portion of a massive galactic empire. The cinematic medium has a harder time with this because of runtime limitations, and Dune is too big for the small screen. But video games do not face the “too much information” problem, as they can turn it all into good playable content.

Surprisingly, Virgin Games wanted to try its luck with a full-blown RTS too, in the form of Dune II. Oddly, Dune and Dune II were released only months apart, – they had been developed by different studios as rival projects under the same publisher’s umbrella.

Beyond the basic DNA, Dune II, developed by Westwood Studios, had very little in common with Cryo’s game. In fact, it was titled Dune II (with two different subtitles) only because it ended its development later. It was released just in time for Christmas 1992 and also found great success, establishing a new standard for strategy games. This is a bit of buried game history, but set up a lot of what we’d see later in the Command & Conquer series, born from Westwood as well, and in the first Warcraft.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Okay, so both an adventure-RTS hybrid and a complete RTS made a splash in the early 90s. But did that happen because of their quality or because of the property they were based on? Looking back, Dune wasn’t very hot around that time. Lynch’s film had left a sour taste in people’s mouths, and avid book readers were the ones keeping the flame alive for future audiovisual adaptations. Building those games on top of an already-established property saved game companies precious time and wasn’t as risky as coming up with something new, but that was it. The gameplay is likely what made these titles successful, rather than the ‘Dune’ name, and that became evident with Dune II.

Here’s the thing: there’s so much to unpack in each of Frank Herbert’s novels (and his son’s if you’re into them) – the Dune universe follows common patterns, but constantly tears them down. The iconography that has been solidified is that of the sandworms and maybe the stillsuit-wearing, blue-eyed Fremen. But Dune is so much more than that, and most games past the first one seemed to forget about its uniqueness, an untapped strength that was pushed aside in order to instead work with familiar blueprints. Even if people didn’t care much for Dune, it was an IP that could’ve pushed those strategy titles in fresher directions if it had been utilized properly.

Arrakis is ripe for the taking

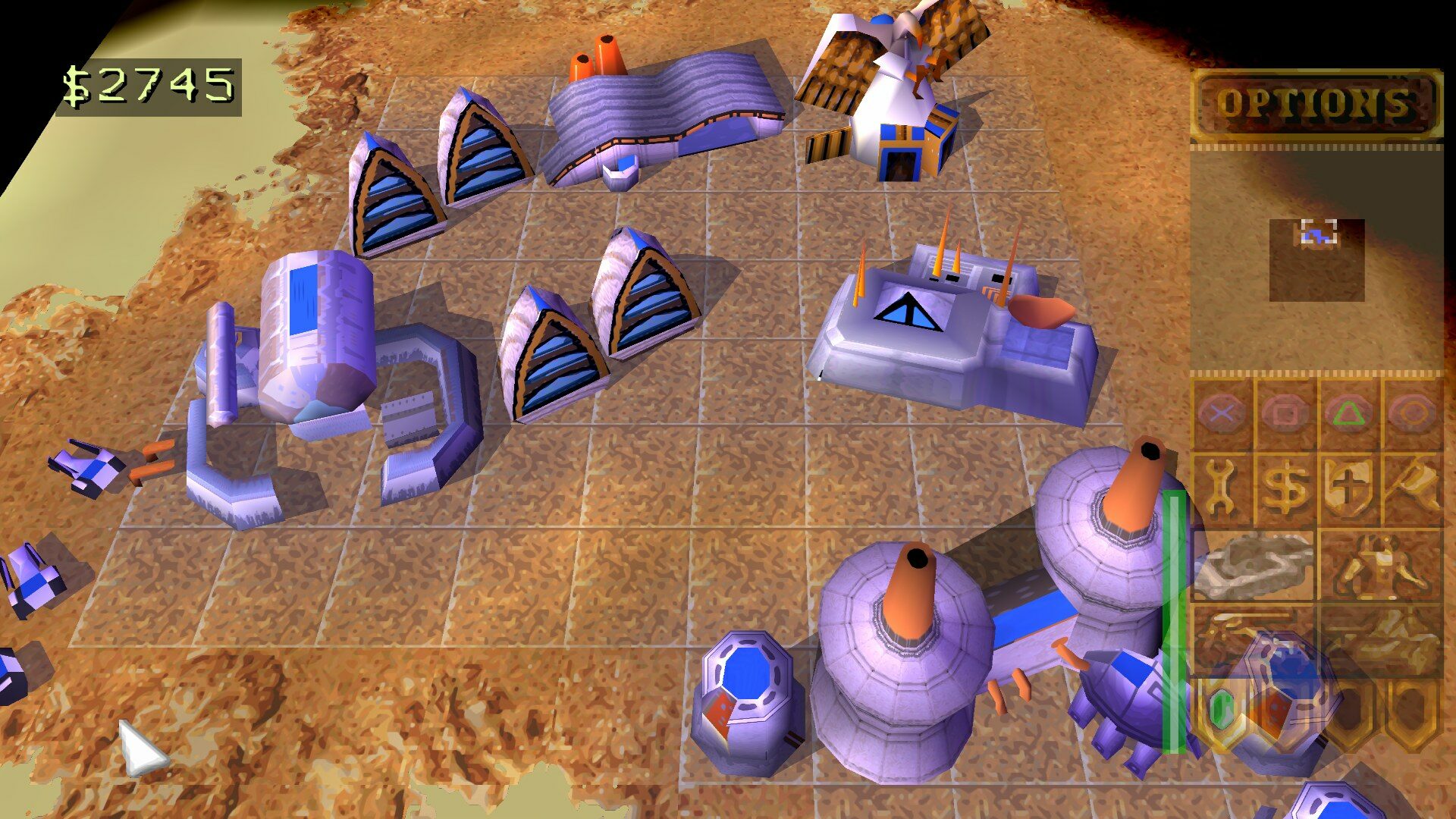

Look, we’re not saying Dune II, later remade as Dune 2000, is a bad game, because it isn’t, but it set the IP on a path of conformity and diluted identity, giving birth to projects (later handled by EA) that felt like Command & Conquer mods. Anyone into the books knows why that’s a problem and nullifies what makes the universe special. For starters: no waving guns and lasers around to battle, that’s the most not-Dune thing ever.

Dune II already showed signs of creative confusion by using a non-canon faction, House Ordos, instead of coming up with an interesting Fremen faction that barely resembled the other two (Atreides and Harkonnen). Furthermore, big pew-pew vehicles slowly took over – it got ridiculous in 2001’s Emperor: Battle for Dune – because big sci-fi means Star Wars-y tanks and ships, right? There were plenty of properties doing that already, and the world of Arrakis was asking for something not nearly as explosive.

Dune games went underground after Cryo somehow got its hands on the IP again to come up with a tie-in game for Frank Herbert’s Dune, a Sci-Fi Channel miniseries released in 2000. It was a costly flop that didn’t land many of its shots, but it doubled down on the inherent weirdness of the universe and went back to the story-heavy gaming roots of the franchise in spite of some canonical compromises. We could see something like that working now, as gamers have grown to love character-driven experiences. And that’s just one possibility.

We still don’t know whether or not Denis Villeneuve’s Dune will find enough money in the sands of Arrakis to kickstart a film franchise, but it has certainly gotten people talking and diving into Herbert’s expansive universe again. People like weird, especially in their video games – Dune doesn’t have to follow “safe” aesthetics or design decisions anymore, as many sci-fi properties have come and gone while it hibernated. With open-world RPGs, cinematic narrative games, and RTS titles now having massive followings, it might be the perfect time to sprinkle some spice on top of those genres.

- How to watch Dune online: release times, streaming services and more explained

- Adapting Dune: Denis Villeneuve on bringing Frank Herbert’s sci-fi epic to life