#FreeSenegal: who's behind the West African cyber-revolution

Armed with VPNs, Senegalese protesters are cutting through the thick blanket of censorship

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It was June 4, and Senegal just entered the fourth day of political unrest following the incarceration of the main opposition leader Ousmane Sonko. Angry citizens took to the street to protest overall social and economic injustices afflicting what's thought to be one of the longest and most successful democracies in West Africa.

Yet, last week's images tell a very different story. Footages of police officers employing disproportionate force and arbitrary arrests to crack down on the rallies float around the web. At least 24 people have been killed and 390 injured during the violent clashes so far, according to the latest data. About 500 were detained, including minors, and many others are still missing. The toll is likely to be even higher.

The fight wasn't battled on the streets only, though. As often happens nowadays, the online world quickly became a very important and contested front to control.

"People linked to the President were trying to give out false information about what was happening," Kaya, a Dakar-based medical student who eschewed her real name for security reasons, told me.

She isn't (or rather, wasn't) an activist, she's a 26-year-old woman fed up with a political system that keeps repressing dissident voices. Right from her room, the same spot where she spent many long days studying for the next exam, she wanted to do her best to support those facing bullets across the main squares of her city.

"This is when I shared the first tweet, so that other users on Twitter could go and back up the post. I had a high number of likes and retweets, which I would not have usually. It was just because of the power of the hashtag."

We are reaching more and more people abroad, please keep feeding the hashtag 🙏We have so much to denounce, we must let them know. We don't know what's their next move is, so let's keep sharing the facts before we're cut from any means of communication.#FreeSenegalJune 5, 2023

At that point, restrictions on social media had been enforced since the evening of June 1. But Kaya knew she had to keep the information flow going in and out of the country. Her and many other citizens' truths about Senegal's events needed to be heard, she thought. At that time, UK-based internet watchdog NetBlocks noted how the measures could be overcome by using a virtual private network.

Armed with a VPN service, it was relatively easy for Kaya and many other users to find a way to cut through the thick blanket of censorship wracking Senegal's social media. The hashtags #FreeSenegal and #MackyDémission (calling for the resignation of the current Senegal President Macky Sall, who's been in power since 2012) quickly went viral.

It might have been this ease of accessing all the most popular platforms that went down—including Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram, YouTube, and Telegram—the reason why authorities decided to also cut mobile internet connections, starting on June 4. These curfew-style blackouts would be staying in place for the following two days.

Allegedly enforced to halt hate speech spreading across the web, these measures strongly affect citizens. Neither a secure VPN, Tor browser nor any other circumvention tool can help in case of total shutdown, in fact. Yet, the blocks didn't stop the people online from posting their discontent. Quite the opposite actually, Senegal's cyber-resistance got even more momentum.

The Senegalese cyber-resistance

Twitter, Reddit, TikTok, WhatsApp: these seem to be the favorite platforms of Senegal cyber-resistance, so far. At the time of writing, there are more than 200 accounts including #FreeSenegal in their handle on Twitter only. The hashtag now counts 3.6 million engagements with a potential reach of over 737 million—according to the social analytics tool Talkwalker.

Short tweets and other posts are used to share the accounts coming from the streets and make images and footage showing the violent crackdown on protesters quickly floating on the web. Twitter chats, longer threads, and short videos are then used to lucidly analyze the events, especially by independent journalists or social societies' profiles.

If their weapons are diversified, their message looks consistent: "Senegal is no democracy and the government needs to be held to account." The sentiment of discontent also reached the Senegalese diaspora, including those living across France, Spain, Italy, and the US.

"Our goal was to let the international community know what's happening here so that they can put some pressure on the actual President," Kaya told me.

6th Question on oppression of the media.#FreeSenegal @AFRICTIVISTES @autruicomoi @Usmaan_Aali @ndeyeaidadia pic.twitter.com/D30UNWlFd8June 8, 2023

Despite Senegal being considered the best democracy of West Africa, the Macky Presidency isn't new to silencing the opposition. Since he came to power in 2012, many political opponents have been found mysteriously guilty of some crimes and excluded from running against him.

The recent events came as main opposition leader Ousmane Sonko got sentenced to two-year jail time on charges of "corrupting youth" on May 30. His supporters believe that these allegations are just another ploy to prevent him—the favorite leader, especially among the youth—to run for the next election in February 2024.

When the charges of an alleged rape were first made public on March 2021, four days of protests ended up with 14 people killed and many more injured. After that, the government took a stronger grip on both press freedom and freedom of expression. Several journalists and commentators have been detained or harassed just for expressing their opinions.

"We are in a democratic country and they [authorities] shouldn't act like that. People are very angry as this term is almost over, but he [President Macky Sall] is still hungry for more. More power, more wealth, more everything. He's just ignoring us," said Kaya, describing Sonko's sentence as just the "last drop" on a society wracked by injustices, corruption, poverty, and rampant youth unemployment.

In fact, the youth in Senegal seems to see Sonko as "the leader they have always dreamed of having at their head. Someone with clean hands," tweeted journalist Ayoba FAYE. No wonder why they are ready to start a revolution to hold on to that promise of radical change.

Fighting back against internet outages

As more and more people filled the feeds across social media platforms with commentaries and images of the clashes between protesters and police, the President ordered to pull the plug from the internet. Even the signal of a local independent TV channel, WalfTV has been suspended until July 1.

The government claimed these restrictions came to halt hate-speech growing online. Yet, these measures had been deemed illegal by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in 2020.

Even worse as "this isn't a first for Senegal—in 2021 authorities briefly imposed similar measures when [Ousmane] Sonko was detained, paving the way for more censorship," Isik Mater, Director of Research at NetBlocks, told TechRadar.

Twitter, Reddit, TikTok, WhatsApp: these seem to be the favorite platforms of Senegal cyber-resistance, so far.

Internet shutdowns are a worrying practice, as they have a huge negative impact on citizens' well-being. They curb people's freedom of speech and the right to freely access news.

They also have a massive effect on the country's economy as they can quickly paralyze several sectors. That's especially true in a country like Senegal where the great majority of citizens cannot afford Wi-Fi connections. According to data coming from Top10VPN, these restrictions have already cost over $16 million and affected more than 8 million people so far.

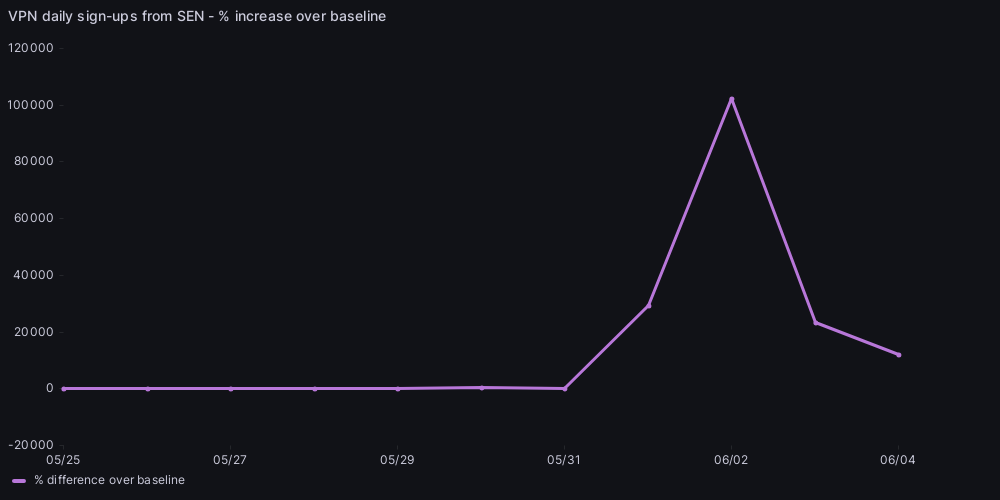

The disruptions on mobile data have now been lifted. But, according to some commentators, some social media apps appear to still be restricted. That's why VPN usage has been high since the start of June. ProtonVPN, for example, saw a 100,000% increase in sign-ups compared to normal levels.

"The numbers we’re seeing are comparable to those we saw in Senegal in March 2021 during the outbreak of public protests," a Proton spokesperson told TechRadar. "It illustrates the importance of being able to access a free and uncensored internet and people's efforts to access free information despite government attempts to censor."

Also using such a security software has its drawbacks, though. For example, Kaya lamented that the hashtags that are so popular abroad were shadowbanned by the algorithm in Senegal.

That's because a VPN spoofs people's IP address location to make them appear as if they're browsing from another country completely. Hence, while the ISP got tricked to think they were outside of Senegal and granted them access to the platforms, the posts were resulting as they've been shared from elsewhere.

Keeping the information flowing across the people inside the country was then a challenge, especially considering that local media were worryingly burying the truth, said Kaya. "I have a very hard time convincing my parents that policemen were actually killing people on the street 'cause they were just watching TV," she said.

Independent journalists and social societies are facing even bigger difficulties trying to report on all the events as accurately as possible while trying to get hold of victims and their families.

Moussa Ngom, who worked for La Maison Des Reporters, a collective of visual journalists, to identify and map out the deaths linked to these events, said the restrictions have created major issues, especially affecting the communication between teams.

"This has greatly delayed our work and it also affects the operation of the newsrooms since the journalists who have to transmit videos have to get around this obstacle," he said.

A new Arab Spring-like movement?

With new (unauthorized) protests scheduled for June 9 and 10 in and out of Senegal, the fight looks anything but done.

"This time is different," said Kaya, referring to March 2021 protests. "We are more and more confident after these two years that the allegations were just to cut off the opposition. We cannot accept this anymore."

While more and more Senegalese people are reported to be jailed for what they post on social media, she doesn't seem scared of these risks. "He's just a human being, just like every one of us. And one day he's going to respond."

From an activist's perspective, we are already united.

Sally Bilaly, Conakry-based reporter

What's certain now is that neighboring countries are watching the situation closely. Senegal is, in fact, the third government in West Africa to have restricted the internet to clamp down on protests since May 17 when social media in Guinea first went dark. Then Mauritania followed, a country that Surfshark indicates as one of the 14 nations breaking its promises to uphold a free internet.

So, what are the chances for Senegal's cyber-resistance to provoke a domino effect in the region echoing the Arab Spring in 2011?

According to Ngom, based in Senegal, this is quite unlikely to happen. Yet, he thinks if Macky Sall would finally step down amid the public pressure, this could positively affect the public opinion in neighbouring countries facing similar issues.

Of a slightly different opinion is Conakry-based reporter Sally Bilaly, who's attentively following the events unrolling on the other side of the border.

He said: "It is not just a Senegalese fight, it is a fight that concerns all pro-democracy citizens of the African continent. There is no anti-government sentiment, there are just rulers who do not want to respect democratic rules."

"Today, we use all the channels at our disposal to follow and participate in the citizen resistance in Senegal. From an activist's perspective, we are already united."

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

Chiara is a multimedia journalist committed to covering stories to help promote the rights and denounce the abuses of the digital side of life – wherever cybersecurity, markets, and politics tangle up. She believes an open, uncensored, and private internet is a basic human need and wants to use her knowledge of VPNs to help readers take back control. She writes news, interviews, and analysis on data privacy, online censorship, digital rights, tech policies, and security software, with a special focus on VPNs, for TechRadar and TechRadar Pro. Got a story, tip-off, or something tech-interesting to say? Reach out to chiara.castro@futurenet.com