Before Mass Effect, RPGs 'didn’t have the excitement to keep people's attention'

Bio lab

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Knights of the Old Republic was turn-based. Yes, it moved in real-time, but behind that flimsy facade, dice rolled back and forth and skirmishes were resolved according to a strict ruleset. Despite its popularity on the Xbox, this breakout Star Wars hit remained deeply rooted in the tabletop D&D milieu that had produced Baldur’s Gate and Bioware as we first knew it.

“We would turn the controller over to people, and they started pressing buttons like crazy, as though it’s an action game, because it looked like an action game,” project director Casey Hudson remembers, who spoke to TRG for a comprehensive retrospective on the making of Mass Effect.

“They would be breaking it all over the place, because it was turn-based and the game was waiting for you to pick your turns.” Ultimately, Hudson and his team solved the issue by creating distinct combat and exploration phases for KOTOR, retreating into the familiar, formalist style of previous Bioware RPGs. But when they moved onto their next project, Mass Effect, they doubled down – delving further into the action game space and creating an unholy cross-breed.

Its success paved the way for Mass Effect to take that model further. Without KOTOR, Mass Effect would not have happened

Trent Oster

“KOTOR was starting to bridge into this third-person, chase cam, interactive conversation world,” Bioware co-founder Trent Oster says. “And its success really paved the way for Mass Effect to take that model further. I think without KOTOR, Mass Effect would not have happened.”

Bioware wasn’t entirely out on its own – it had some industry precedent to draw from. “Early on, there was this emerging genre of action RPGs,” lead designer Preston Watamaniuk says. “Deus Ex was the first that gave you light action gameplay, systemic gameplay, simulation gameplay, good progression and stuff like that. And it was this interesting hybrid, innovative for its time.”

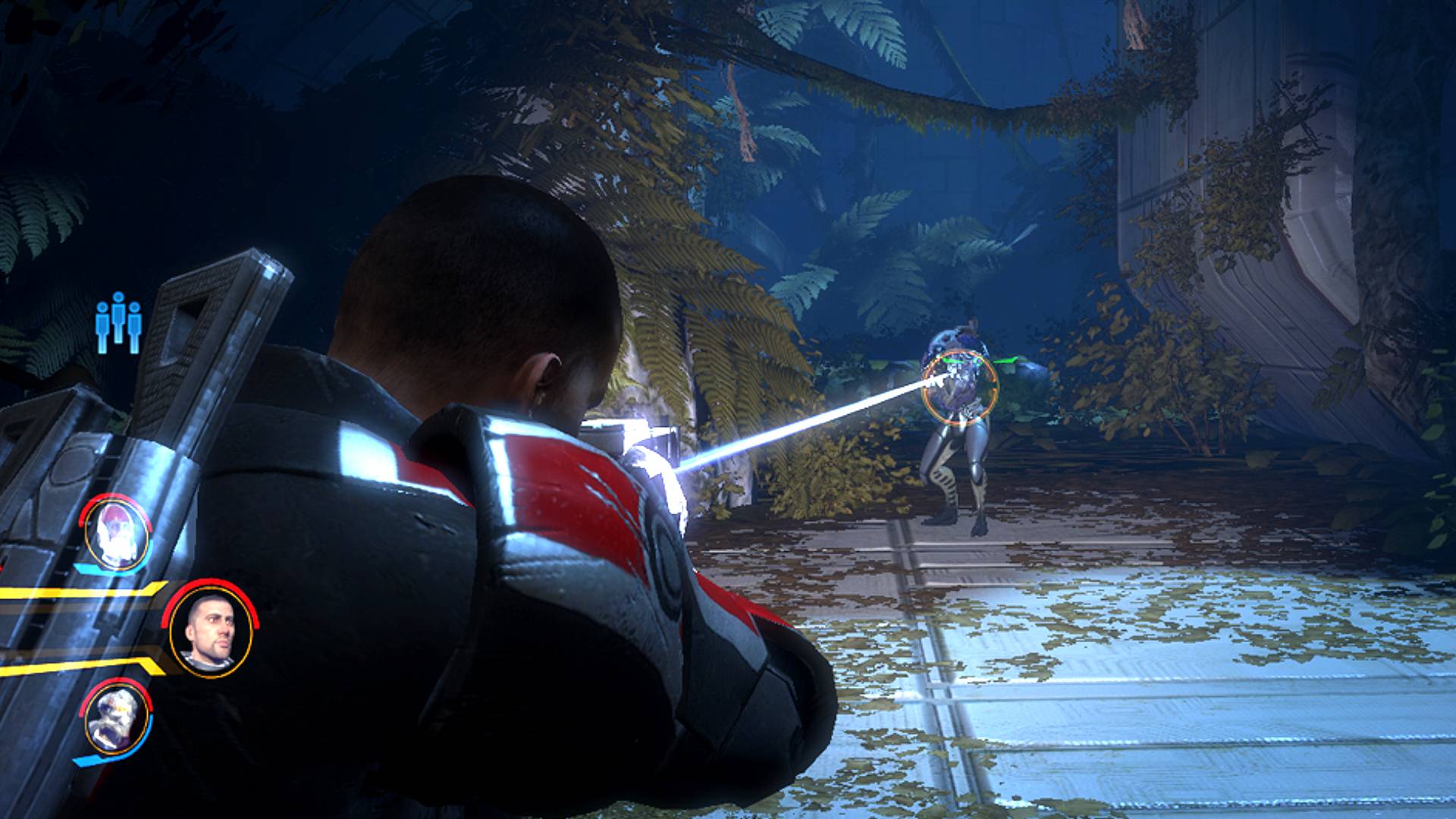

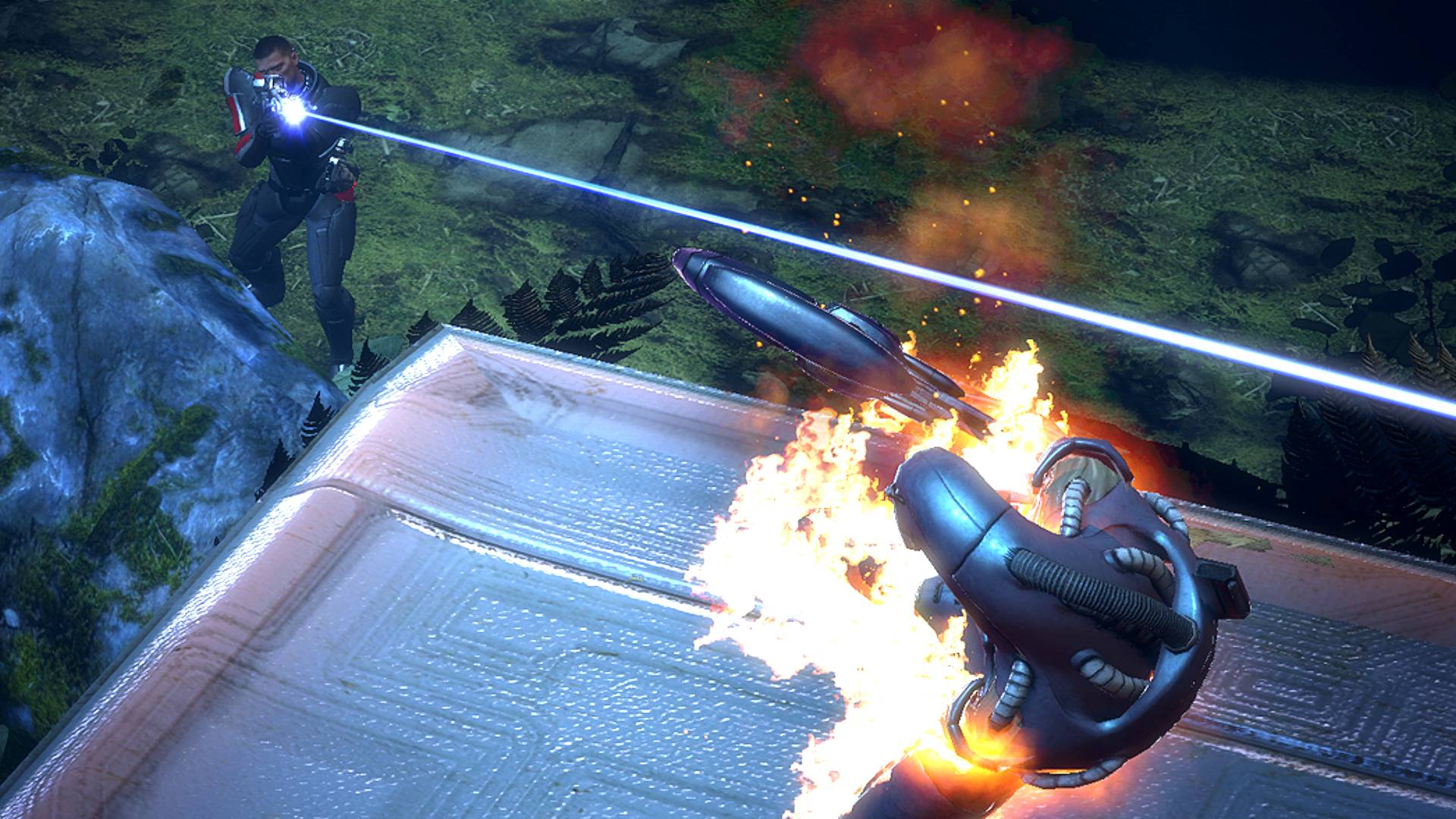

The Mass Effect team even experimented with similar solutions to Deus Ex when it came to blending shooter and RPG systems. “The challenge through development was, we hadn’t really cracked an approach for how to create that balance,” Hudson says. “We were trying ideas like, ‘Well, maybe your accuracy is affected by your character's aiming ability’. So we had a reticule that got really big, and you’re shooting all over the place if your character was not very skilled. Which is frustrating if the player is skilled.”

Target practice

Lead effects artist Shareef Shanawany was invited to sit in on early combat design meetings. “We just did a huge roundtable and threw out ideas for the mind powers and special weapons,” he says. “It was fun to let our imaginations go wild. We had to invent a lot of new things involving combat that the studio hadn’t done before.”

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

I think everyone looked at Gears of War and was like, ‘Oh, man, everything about that combat is next level'

Mike Spalding

The team picked Unreal Engine 3 in part for its “rich established first-person shooter history”. But Gears of War was yet to come out, and it intimidated Bioware when it appeared onstage at E3. “I think everyone looked at that and was like, ‘Oh, man, everything about that combat is next level,’” lead character artist Mike Spalding says. “We instantly knew that was the new bar. I remember folks having to reevaluate what we needed to do in order to start getting close to that – what we perceived as the new standard for over-the-shoulder, third-person combat.”

Bioware worked hard to produce the necessary ‘oomph’ shooter audiences would expect. For example, the FX team developed an impact system, which produced different visual effects depending on what a player was shooting – little chips of rock if they hit a boulder, for instance.

Yet the possibility that Mass Effect might fall between two stools – compromising both RPG and shooter mechanics, and pleasing fans of neither genre – was a “huge worry,” Oster says. “The feeling internally was that there was the old market of top-down isometric D&D fans who wanted a specific thing. We were nervous about losing a lot of RPG fans. But at the same time, I think the team was really optimistic about how far they could push the storytelling, and how far they could make an immersive science fiction world.”

First contact

As history tells us, that optimism was well-founded. And in the end, Mass Effect enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with Gears of War – tech solutions from the former feeding into the latter, and players hopping freely between the two.

People played Mass Effect that weren’t looking for role-playing games and didn’t even realize they were playing an RPG until they got into it

Ryan Hoyle

“People played Mass Effect that weren’t looking for role-playing games,” programmer Ryan Hoyle says. “And they didn’t even realize they were playing an RPG until they got into it. It’s like, ‘Oh, this isn't so bad after all.’”

Before Mass Effect, RPGs “didn’t have the excitement to keep peoples’ attention,” Hoyle argues. “Gears of War might be a little flashier, but when it comes down to it, Mass Effect has all the substance of that, plus so much more with the universe and all the different stories and aliens and locations. I think it really revived [the RPG genre] a lot.”

It was a strange echo, in fact, of Baldur’s Gate – itself a strange hybrid of traditional RPG and newfangled RTS mechanics that wowed audiences in 1998. Like that game, Mass Effect proved so popular, and spawned so many imitators, that it no longer appears at all odd or experimental. “There are two or three really good ARPGs that come out every year now,” Watamaniuk says, “and they have a set of components that is easy to recognize.”

Watamaniuk has worked on every Mass Effect game since that first one – including the upcoming sequel, which he’s “really excited about”. He oversaw the reduction of RPG elements that came with Mass Effect 2, and the slight balance correction that followed in the concluding part of the trilogy. “I think Mass Effect 3 is a true, 100% action RPG,” he says. “Good action, good RPG systems, good story. It was everything coming together in that one place.”

Jeremy is TRG's features editor. He has a decade’s experience across publications like GamesRadar, PC Gamer and Edge, and has been nominated for two games media awards. Jeremy was once told off by the director of Dishonored 2 for not having played Dishonored 2, an error he has since corrected.