Mass Effect: The oral history of a game-changing RPG

Bioware's moon shot

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

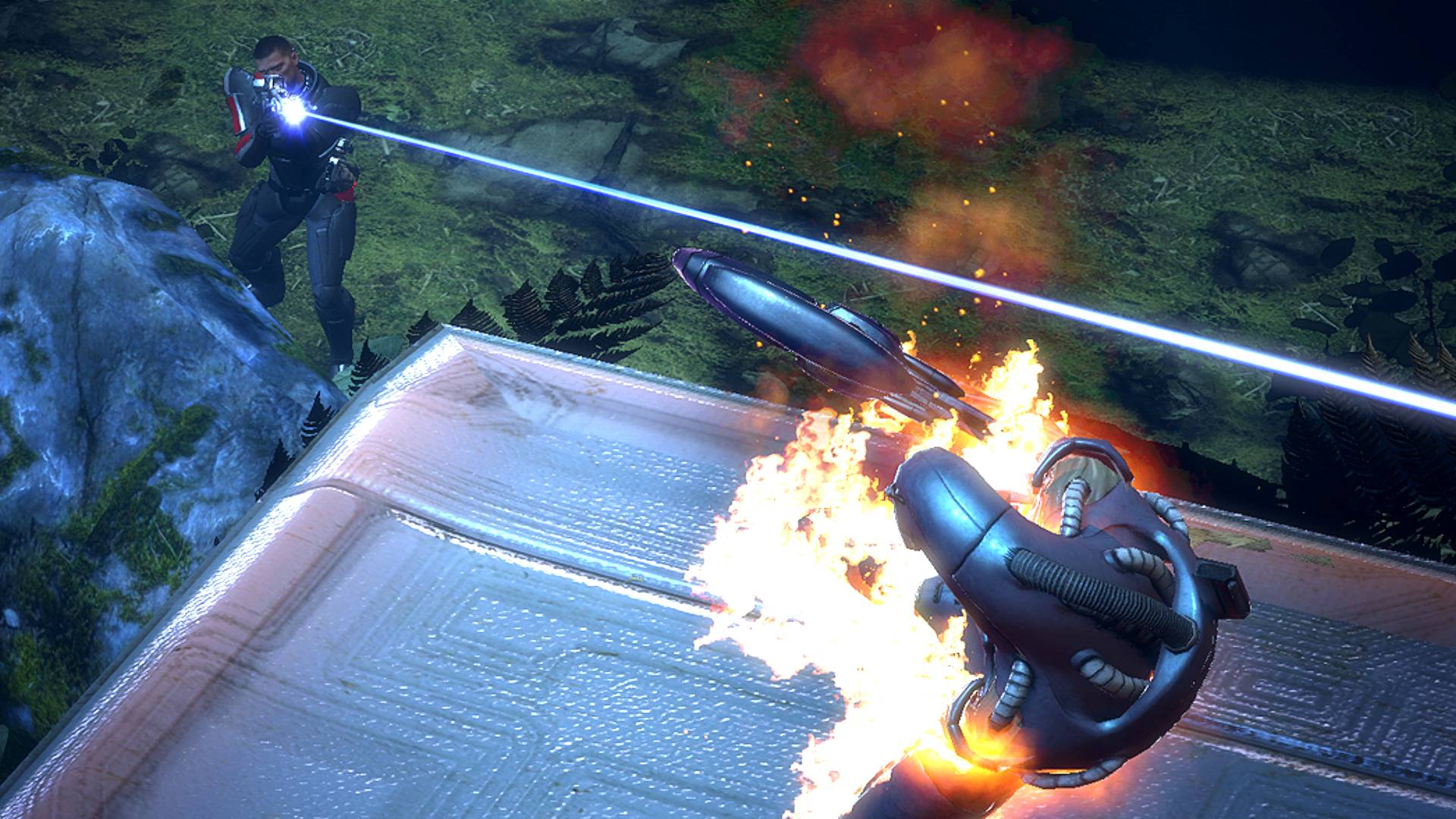

These days we expect our triple-A games to pull us into their worlds with cinematic framing, a believable cast and flowing interactive dialogue. So much so, it’s easy to forget that before Mass Effect we rarely saw anything of the sort.

15 years ago Bioware released the first part of a generation-defining action adventure trilogy that, over time, rewired our expectations. Combining textured characters and meaningful choices with solid third-person shooting, it set new benchmarks for an action-RPG hybrid that we’ve seen countless times since – though rarely with the same detail or strength of identity in its fiction.

Here’s the story of how the first Mass Effect was made, as told by the people who made it. In 2003, the team at Bioware working on Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic (KOTOR) was nearing the end of development and looking towards its next project. At the same time, having made the company’s name with licensed fantasy RPGs such as Baldur’s Gate and Neverwinter Nights, the heads of Bioware wanted to back original IP and build their own worlds. As the genre they’d contributed to began to evolve away from traditional turn-based rule sets, so did the studio.

Life after Star Wars

The core team that had made KOTOR still had the sci-fi bug, but was ready to leave the galaxy far, far away for pastures new.

Trent Oster, Director of Technology and Bioware co-founder: Lucas is great to work with, and working 1,000 years before the movies gave us a lot of freedom to play. But there are also a lot of restrictions on the Star Wars universe and what you can and cannot do. So being able to open up our own canvas and sketch out our own ideas and our own concepts was really exciting. I guess at the time, Star Wars wasn't doing anything, Star Trek hadn't really done anything. All the major science fiction IPs were sleeping at the wheel. I personally thought it was a great time to be doing something like that.

Our thought was, ‘Why don't we have the same fun that we just had making this kind of game, but do it in our own IP?'

Casey Hudson

Casey Hudson, Director: We were super happy with [KOTOR] and just kind of wanted to keep doing more of that. But the sequel would have required us to turn the next game around much faster than we would have wanted. For us, that was a factor in what we wanted to do next. Our thought was, ‘Why don't we have the same fun that we just had making this kind of game, but do it in our own IP, where we can design it from the ground up to be about interactive storytelling?’

Derek Watts, Art Director: I wanted to do the next KOTOR. We did KOTOR 1. KOTOR 2 was given to a different studio. I think we were given the option to do it, but [Bioware presidents] Ray [Muzyka] and Greg [Zeschuk] were looking at the value of our own IP and they were thinking far ahead. So when we went on to Mass Effect, it was all about making something as iconic as Star Wars. But it couldn't look like Star Wars, and that was a challenge.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Ryan Hoyle, Programmer: It was such a huge idea. ‘How do we make something that's fun and interesting that's not just Star Wars, but keep some of the things that made KOTOR so awesome? Like having choice that affects the universe, and maybe even take that on a bigger scale?’

Hudson: There were moments in KOTOR where it felt like it wasn't just puppeteered characters. There were a few moments, almost accidental, where the characters were compelling as digital actors, just on the cusp of that. So it felt like with the power that would be coming out on the next systems, we could probably do something really special with digital acting.

Creating a galaxy

With the concept of a space opera settled, the game needed a name and a ton of design ideas gathered from a range of sources.

Watts: We went through lists of names, and we couldn't really agree on stuff. And I think it was actually Greg Zeschuk who mentioned ‘Mass Effect’. It was one of those things where I didn't love it, and I didn't hate it. People discussed it, and we started to feel like, ‘Yes, we could live with this name.’

We had such high ambitions, and wanted to create our own franchise to rival the likes of Star Wars or Star Trek, it needed to have a uniqueness to it

Shareef Shanawany

Shareef Shanawany, Lead Visual Effects Artist: There were ten names or so that the team had collectively come up with, and it was put to a vote. I distinctly remember ‘Space Age’ was one of the options, which mirrored nicely with Dragon Age. I always liked the old Sierra ‘Quest’ games, so it felt like BioWare could maybe start their own version of it with the ‘Age’ moniker. But there was an interesting argument for the name ‘Mass Effect’. Because we had such high ambitions for the game, and wanted to create our own franchise to rival the likes of Star Wars or Star Trek, it needed to have a uniqueness to it.

Preston Watamaniuk, Lead Designer: Star Trek is an example of space opera done really well. Babylon 5 is another. And I think we were just carrying on those types of traditions. Like, ‘What does a really well thought out, well-constructed space opera look like, with this very specific technological underpinning that we came up with?’

Shanawany: Something [Preston and I] shared was our love of Babylon 5, which I know had a big influence on the game early on. You can see a lot of similarities in the Citadel and the Babylon 5 station, for example; a central spot for all of the alien races to gather. And also the idea of this ancient mythological force in the galaxy and mankind’s rise.

Watts: We needed to agree on one artist or look, and it was [Blade Runner concept artist and futurist] Syd Mead. We couldn't really think of anybody else that was using that style or his influence, and that set the whole tone for the game. But we had to alter it a lot to make it our own. And to be honest if you see Syd Mead’s clothing designs, it's a lot of topless men and other things. It’s like, ‘Well, I’d have a hard time fitting that in and we might get some blowback.’

Steve Sim, Audio Design Lead: The initial debates were, ‘Are we going Star Wars, are we going Blade Runner, as far as the soundtrack goes?’ And obviously we went the Blade Runner route. That was a dream for me, because I'm an electronic music producer, and Casey was right on board too, because he loved a lot of that electronic music, even outside of genres like sci-fi. One of our most influential songs was Love on a Real Train from Tangerine Dream.

I've always said that if Santiago Calatrava plays our game, he's going to flip out because we borrowed so much of his influence

Derek Watts

Watts: All the architecture in the game was referenced through real world architecture we looked at. There's Santiago Calatrava, Zaha Hadid. I've always said that if Santiago Calatrava plays our game, he's going to flip out because we borrowed so much of his influence.

Shane Welbourn, Lead Cinematics Animator: [Casey] had certain movies that he wanted these iconic moments from. And I remember, he had the timeline of the movie The Right Stuff on his computer monitor. He was like, ‘I'm thinking of a moment like this,’ and stopped it at a spot on the timeline. It was like he just randomly clicked. And I was like, ‘OK, either you know that timeline so well, or you’re just randomly picking moments for me to try to create here.’

Watts: The Normandy is Solaris. We were struggling with the Normandy. We weren't sure what to do with it. [The remake of] Solaris had just come out and we looked at that and we said, ‘There's the Normandy, let's make it look like Solaris.’

Another thing we looked at for ships and designs and inspiration is lighting fixtures. You get a lot of ideas for star bases out of that. [If] the light looks good hanging over your dining room table, it might make an interesting star base.

Sim: The pitch I gave to the team was, well, if we're trying to get into this universe of early 80s, late 70s, sci-fi, we should approach the sound design the same way that the sound designers would have back then. So I pitched that we get into the mind of Ben Burtt, the guy that invented the sound design aesthetic of Star Wars, and find out what techniques they used back then.

Mark Meer, Voice of Commander Shepard: I was tasked with determining what a typical member of each species would sound like. Sometimes just the shape of their faces and their biological characteristics would influence how I would approach that. For example, I'm always fond of saying that I'm the reason why the Salarians sound a bit like Steve Buscemi.

Unreal demands

With KOTOR’s Odyssey Engine made for previous generation consoles and Bioware’s Eclipse Engine still in development, the company sought a third-party engine for Mass Effect and settled on Unreal 3 – even though it was unfinished itself.

Oster: We reached out to Valve and to Epic at the time to evaluate both of their technologies. Valve was pretty hilarious, because literally it's like they threw some things over the fence and said, ‘Here it’s yours, play with it, poke it, do what you want.’ And we were like, ‘Um, support, tutorials?’ And they were like, ‘Yeah, you'll figure it out, you’re game devs.’

The Epic side was a lot more supportive, and the idea of us taking [Unreal 3] and putting it into an RPG was really exciting to them. Ultimately, we licensed Unreal before it was complete. So we did what any other normal game developer does – we just started building the pieces we needed that weren't there.

it took us a little bit of time to realize that the engine was built more towards a Gears of War game, and we were trying to do something different

Derk Watts

Watts: The idea was to build that technology for the first game, invest heavily in that and piece it together and hold it together with rubber bands and duct tape to make it to the third game. Then that's probably where that technology would get caught up, on the third game. I think the advantage for us was we got an engine that was strong. But it took us a little bit of time to realize that the engine was built more towards a Gears of War game, and we were trying to do something a little bit different.

Sim: Every one of us was learning brand new tech on the fly that was unfinished. At that moment in time, we were co-developing the Unreal Engine with Epic. Things would shift, often on the Epic side the tech would change a bit, and we'd have to refactor. We'd hook something up and then a month later all those hook ups would have to be disabled and re-hooked up. It was a little bit of a slog in that, and that was what led the entire team into months and months of crunch.

Oster: Throughout the development of Mass Effect, we would be working on the Unreal Engine, and then Unreal would come up with a new drop. And it would take us in some cases four to six months to update to that new drop of the engine because we had changed so many things.

Hoyle: A lot of things we did for Mass Effect ended up going into Gears of War, because we ended up fixing something before they did. But there was always a lot of back and forth like, ‘We're about to try and do this, and it doesn't work right now. Is there something like this coming up that we should wait for?’ And often they’d be like, ‘No, you better just do it, because we're trying to do what we can do right now. So anything you're really going to need, you should rely on yourself.’

Shanawany: I think a few struggled with Unreal at first because it was such a departure from what we had used before, but for FX, Unreal was great. It had a nice particle editor which gave us a lot of control to generate particle effects. The rendering technology was excellent, and the frame buffer effects we were able to come up with really defined the look of the game’s combat.

Mike Spalding, Lead Character Artist: The other thing that was great about Unreal was they had an extremely powerful toolset that had a lot of artist-friendly design. I remember seeing the material editor – it was all node based. It just opened up a whole world of possibilities for artists to use, and to create materials and characters that just weren't possible on a previous generation. From an art perspective, the engine was a phenomenal tool.

Partway through the production, you couldn't even fire up the engine, and that went on a really long time, like four or five months

Shane Welbourn

Welbourn: I love Unreal. Everything about it is just so well documented. So if you don't know how to do something, you can look it up. Also they were really good. I'd send questions directly to them and they would get back to us, they were really trying to support us.

There was a [point] partway through the production where you couldn't even fire up the engine, and that went on a really long time, like four or five months, which is huge. And that totally messed up the design department, they couldn't go into their levels and work on them. It was just so unstable, so they couldn't get their work done. But we were lucky [in the cinematics department] that we could still be plowing along. That saved us, I think, because ultimately when it did come back online, we could just go in.

Germane Shepard

Commander Shepard had to be a certain kind of hero to travel the galaxy as a Spectre – with the right look, voice, personality, and moral possibilities to suit his role as a Citadel agent.

Hudson: At the time, one of the things that was really popular was 24, and Jack Bauer. Obviously, as it’s a show, you only see the one choice he takes. But Jack Bauer is constantly facing agonizing decisions, and the decisions are not, ‘Should I do something completely altruistic’, or ‘Should I just for no reason do something evil?’. Those choices are really not that interesting or realistic. But if you put someone in a situation where they are trying to do good, and there is a choice to be made about whether they do something that is in the near-term less painful, or something that is in the near-term quite brutal but to achieve the greater good? That becomes an interesting choice.

Meer: I think as the games progressed, and as the events of the war wore Shepard down, you were able to have a little more freedom in expressing more emotion. But for the first game, I was directed to be very by-the-books, and to keep my emotions somewhat in check. That goes back to Shepard being a military officer used to working under pressure. You [also] had to keep in mind that there are some people who are not going to be playing pure Renegade or pure Paragon. So you couldn't go too far [emotionally] in either direction, or else somebody playing a middle path game would have these wild mood swings in the dialogue.

Mark Vanderloo was affordable back then, [even though] he was one of the top male models in the world

Derek Watts

Watts: We had [the design] up to a certain point, but it wasn't quite there. So we opened it up to the team. What do you think Shepard should look like? There are a lot of people that took it seriously and a lot of people didn't. Somebody put rugby team player heads on there, and they're all bashed up with tape on their ear. One person, [level artist] Mike Jeffries, did take it seriously. He put George Clooney’s head on there. It was a good picture, he darkened the armor and then he put this little logo on the chest. That for us, as we showed people, we were like, ‘OK, this is going in the right direction.’ Not because of George Clooney, but a bit of that look – the short hair, square jaw.

[Then] there was an art director at Bioware, and he had this magazine on his desk and I took it when he left and Mark Vanderloo was on the cover. And I took that picture and put it on Shepard and it just seemed to work. He didn't have that all-American look, more of a kind of a European look to his face. It wasn't that over-the-top jock look that we were trying to avoid.

We were surprised that we could actually scan [Vanderloo] in. He was affordable back then, [even though] he was one of the top male models in the world. We also picked him because then we could say, ‘Hey, we're trying to get the most attractive male in there, so when we put in attractive females, you balance it out – we're trying to get equal representation for both.’

Welbourn: I’m watching the actor do some of the scenes and you can see on the mo-cap he's got a bad back. So we find out that he actually just injured his back, and we can't use this. [Shepard’s] supposed to be a hero. It was subtle, he was doing his best to not look strained but you can really see it. So I ended up going in the [mo-cap] suit. The majority of Shepard’s movements actually ended up being myself. One of the producers, Shauna Perry, who was there coordinating everything, she's like, ‘I don't know about this.’ She was pointing out how gangly I moved. Sometimes I could go a little Jar Jar Binks.

The crunch

The task of creating a new IP on a new engine for a new console took its toll, and the team were working long hours at all costs.

It took a lot of years to realize that this isn't a healthy way to live your life

Casey Hudson

Hudson: I started very entry-level [at Bioware] as a technical artist, and I just spent every waking moment that I could trying to learn about how things worked. You wouldn't be able to keep me away, because I just wanted to figure out how everyone did their jobs, so I was just at work all the time and loving it. Then we rolled onto Mass Effect 1, and by then I had been doing four years of crunch time. And it was like a way of life that, in retrospect, you realize is not a healthy way to live for yourself and for other people. So I think, as we got later in the Mass Effect series, we realized more and more that we had to try and find some better balance. But it took a lot of years to realize that this isn't a healthy way to live your life.

Hoyle: Bioware has, especially on a new project, this very big view of all these amazing things and features, and we always bit off more than we could chew. So trying to get the balance down in that final year of, ‘What are we keeping? What are we cutting? What needs to be fixed up?’ There was a lot of work and not enough people to do it.

But it wasn't somebody cracking the whip saying, ‘Everybody go finish the game by X date.’ It was more that we really believed in it and wanted to get it done. Afterwards, people were like, ‘Yeah, that was too much.’ But at the time, there were very few people who were going crazy or anything like that. People were encouraged to go home if they wanted to, and see their loved ones. The atmosphere and the culture was really good. It was toxic only because it was not managed perfectly, and people were new and didn't really know when to say no.

Sim: A 60-hour week was a normal week, but there even came a point where we were working seven-day weeks, and there weren’t breaks for a very long time. You need to have a good work and home balance at any given time in a production cycle, so it was what I would consider a death march crunch.

Watamaniuk: There's crunch because you're super excited about what you're doing. There's crunch where your bosses challenge you, and you know that it's going to make what you're working on better. Then there’s change management, like, ‘Hey, something in the engine changed, or we had to cut a gameplay feature that has a ripple effect, or we just thought this would take less time and it didn't.’

When you're dealing with new IP, with new gameplay systems, change management becomes almost a daily process. So yes, there were late nights, and we worked very, very hard. Because that change management introduced a lot of requirements where you're working that third type of crunch. There was also the first and second types of crunch as well – where I worked late nights because I knew what I was doing was making the project better, and I was excited about the project.

They could just go into a room, scream a bit, get frustrations out, and we would record it and move on

Steve Sim

Sim: What we used to do as a bit of comic relief from that is, being the audio department, we would have screaming sessions. We would say, ‘Come into this office at this time, we've got microphones set up, give us your best primal scream that we can use in the game for creatures, and sign this release.’ And a lot of people signed up for it and had fun. They could just go into a room, scream a bit, get frustrations out, and we would record it and move on.

Welbourn: It was tough, because it was long hours, it was crazy. Nobody wants that. But luckily I didn't have any kids, and my wife was working on Dragon Age, so at least I could go downstairs and see her once in a while. But Derek had twins right near the start, and I barely even saw Derek on the whole production. Most of the time he was just so tired, poor guy.

Watts: Yeah, I had twins, right in the production, my wife and I had twin boys, trying to deal with that. So, long hours at work and at home. But it felt like you were doing something important. ‘We’re all on board, this is challenging, we're making this step for fidelity, and it's going to be worth it.’ And it was.

Welbourn: The amount of crunch we did, it's horrible, I don't stand by crunch. But you do need to put the time in to do it well, and if you're passionate about it, it doesn't feel like crunch – as long as you're not wasting your life away doing it. I'd rather be making a game than playing them, a lot of times. So it works out well for me.

Watts: It was a challenging project, there was stress on it. But also I think it was a project that when you finish it, you look back on it and you go, ‘Wow, it really paid off. It was really worth it.’ And then we took all that knowledge and did Mass Effect 2, which I think was one of the easier games I've ever made.

My last day at Bioware was my first day working on Mass Effect 2. I sat down at my desk and I went, ‘I don't think I can do this again.’

Steve Sim

Sim: I was super happy with what our team accomplished, I was happy that the game got shipped. But my attitude was that I didn't want to do it again. And what I tell people is that my last day at Bioware was my first day working on Mass Effect 2. I sat down at my desk and I went, ‘I don't think I can do this again.’ After I left Bioware I worked on a golf course cutting grass. Just left completely. Yeah, I needed the brain break.

Critical mass

Despite the setbacks and scope of the project, Mass Effect finally starts to come together as the team prepares a demo for E3 2006.

Oster: The E3 demo, actually getting it to work and getting it functioning and getting a performance, that was a real ‘come to Jesus’ moment. That was when all the aspirations ran into the brick wall of reality, and it was like, ‘This is what the engine can do.’ Because going into that demo, there was a lot of confusion about, ‘Well, what exactly is it, how much can we do?’ And that demo solidified it.

Until you pull things together, it's all sort of theoretical, and you think you know what game you're making

Casey Hudson

Hudson: The interesting thing about [the E3 demo] was that it was the first time we pulled together playable moments in the engine that really proved to us what the game was capable of. Then once you have that, you can start making that game. Until you pull things together, it's all sort of theoretical, and you think you know what game you're making. But once you have that moment in time, where everything's pulled together, you know exactly what the game needs to be.

Watamaniuk: When you build a vertical slice like that, and it actually feels like what you want to make, it has massive positive knock-on effects. After that demo, we had a better idea of what our technological challenges were, we understood some of the gameplay challenges, obviously, that we had left, because you'll note there are systems in that demo that do not exist in the final game. But the biggest benefit was that the team understood what we were building and was able to then work autonomously, without as much hands-on direction, to produce something amazing.

Spalding: There was this graph that Casey showed us, and I remember it was of an exponential curve, and mapping game development to that curve. You start to understand where things are at a given stage in production. There's a lot of really hard work that goes into making a game, and it still stays at that bottom end of the curve. And having a clear vision, having great leadership and support, it's tough as the curve starts to increase, but once you get into that elbow, everything just starts to come together. That's where the team really starts to pick up momentum.

That goal you thought was impossible suddenly comes into focus, and it’s an exciting time to see all the fruits of everyone’s labor converging

Shareef Shanawany

Shanawany: It was a little daunting, the sheer amount of work we had left to do, and it felt like an impossible task to be able to finish all the content we had in time. But a funny thing happens, where every day you make a little progress, and then the next day you build on that, until eventually you realize whole portions of the game are starting to come together. That goal you thought at first was impossible suddenly comes into focus, and it’s an incredibly exciting time to see all the fruits of everyone’s labor all converging at the same time and the game taking shape.

Welbourn: You could tell it was something, although there was one moment that it finally really occurred to everyone, I think. And it's that first little moment on the Normandy, when you're watching the screen with the footage from Eden Prime. We had our team leads meeting, and we watched that, and it all just came together. We were like, ‘Ah, this is good.’

The weird thing about that – maybe I shouldn't say this – we had a meeting with Microsoft. A couple of us had to go in and tell them that we were going to be delivering the game in two months, which was what we were supposed to be doing, but we were nowhere close to it. But I think there was a confidence there, of what we had and what needed to be done to polish it up. So it was a no-brainer.

Elevated expectations

During development, Bioware (along with Pandemic Studios) is bought by the ambitious, Bono-linked private equity firm Elevation Partners. It’s then sold to EA just before Mass Effect’s release.

Hudson: When you're a truly independent company, there is always, even though Greg and Ray shielded us from it quite well, there's always the concern. ‘If we did need to extend our project, is the money there? And what if this doesn't do well, can we do another one?’ So having additional financial security is always a good thing. It was actually a really exciting time.

Oster: Elevation had a really interesting concept. They wanted to be this next-generation, IP/development/publisher. They basically wanted to find a couple of superstar studios, and build a new publishing entity around that.

‘There's no way I'm going to be at the meeting where they tell us they’ve got to close down Bioware, and I'm like sad Destro.’

Shane Welbourn

Welbourn: The meeting where they told us that Bioware and Pandemic got bought by Elevation Partners, I thought they were going to tell us Bioware was going down. Because I looked at the budget for Jade Empire, and I'm like, ‘I don't know if we’re going to sell that many copies.’ I remember it because it was also Halloween, and my wife had dressed up as [GI Joe’s] the Baroness and I was supposed to dress up as Destro. And I'm like, ‘There's no way I'm going to be at the meeting where they tell us they’ve got to close down Bioware, and I'm like sad Destro.’ But yeah, it all turned out well.

Hoyle: When Elevation happened, it was just a giant celebration, everybody was very excited. It was a really cool thing, and nobody necessarily expected it. And it was seen as generally a really positive thing of like, ‘We're doing well, and we're getting recognized for that.’ And they certainly didn't really interfere with anything we were doing. So it didn't really change anything.

Sim: The whole Elevation Partners thing was almost invisible to a lot of us then. There was one high point because one of the owners was Bono from U2. So Casey showed me an email that he got from Bono praising some of the sounds and specifically the logo sound. He’s saying, ‘Oh, that sound you guys have for the logo is great. It's a perfect fit. How did you do that?’ So that was kind of cool.

Oster: We went to Elevation Partners and we're like, ‘Hey, guys, so our budget just doubled.’ And the Pandemic team that had been acquired said the same thing. So, Elevation Partners was like, ‘Oh, my God, we just got into game development and all of our financial plans, you've just told me the costs are doubling. Oh, wow, this is not so great.’ And then luckily, a couple years later, they were able to sell everybody off to Electronic Arts, which made life a little easier for them.

The biggest change was in the language, especially amongst producers and that crowd. They were assimilating into the Borg, it seemed

Steve Sim

Sim: What I noticed once EA came in was how the language changed at work, and started adopting more corporate-isms, like the language of corporate America. At one time if you needed help on a project, you'd say, ‘I need more guys,’ or ‘I need more people to help me out with this.’ And then it turned into, ‘I need more resources.’ So the biggest change I found was just the change in the language, especially amongst producers and that type of crowd. They were assimilating into the Borg, it seemed.

Oster: It became a little weird under Electronic Arts, because when we were acquired we were all looking forward to it like, ‘Yeah, we're owned by EA, they're going to give us a budget, we finally don't have to keep constraining ourselves and crushing things down and cutting corners.’ And one of the first things they did was like, ‘OK, based on your budgets, we need to cut across the company 10%.’ And we were like, ‘Oh, so we're not getting more, we're getting less.’ That was a bit of the EA feeling. We call it the EA butter knife. It just seemed arbitrary, and not very smart.

Watamaniuk: Casey, Ray and Greg were always very good at managing those external changes of ownership, changes of executive leadership. They really did an amazing job shielding the team from all of that. They would tell us, ‘Guess what, we just got bought by EA,’ or, ‘We're being sold to whoever.’ Then you'd be like, ‘Oh, OK,’ and go back to work.

There are people that have thoughts going in about, ‘Well, what does it mean to be sold to Elevation Partners, and what does it mean to work for EA?’ They always come into these things with biases. I've always been like, ‘Well, OK, instead of worrying about this stuff ahead of time, why don't you wait and see what the actual impact will be? And meanwhile, focus on making a good game.’

The finish line

The game is complete in time for release at the end of 2007, and the team is mostly pleased with what they’ve created.

Hudson: I think we knew both with KOTOR and with Mass Effect 1 that we loved it, we were having fun playing with it. We really liked the story and the characters and everything. So then it's just, ‘We hope that we're right.’ And other people really liked it as much as we did.

Watts: We weren't thinking this is going to be a 96% game, the best game of all time. There was no thought of that. I think the idea was, ‘Let's make a good game to set us up for the franchise. We can fix this stuff on a second game, we can get better.’

It wasn't as bad in the real world as what was in my mind, obviously – all the tape and cracks and everything else

Ryan Hoyle

Hoyle: For me personally, just because I knew all of the technical shenanigans, there were things that I was like, ‘Oh, I can't wait for Mass Effect 2, I'm going to fix this, I'm going to fix this.’ There was so much in my mind to fix but it wasn't as bad in the real world as what was in my mind, obviously – all the tape and cracks and everything else.

Watamaniuk: I was happy with it, but I also understood that there were things that we could have made better. I went through an extremely exhaustive analysis of all the reviews, fan feedback, everything going into Mass Effect 2.

[In retrospect] there were very simple things I could have done to Mass Effect 1 to make it a much more enjoyable, understandable, more elegant experience. Just at the time, it's very hard when you're in the weeds to see beyond the weeds. But I would have simplified some of the progression systems. It had very much a looter-shooter treasure system. It doesn't belong. I don't think looter-shooter treasure belongs in a Mass Effect game.

Hoyle: When I watch Mass Effect, and I see you walk into a room and it takes time for the texture to show up on something, it drives me nuts.

Meer: I'm a gamer. I'm a nerd. So getting to be the main character in a video game like this was a dream come true. And getting to play it and essentially just realizing like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is what we made.’

Even if it had failed, I think we would have all been happy still. It was our little baby

Shane Welbourn

Welbourn: I don't know if you remember the first time the game came out, but it had loading issues, sometimes on the cinematic stuff. None of that was there until basically we were trying to finalize the game, and they realized that they couldn’t load the level fast enough. To me, we'd put all this energy into it, and it would have been nice to have [a little more time]. But overall, I think we were pretty confident on what kind of reception it was going to get. Even if it had failed, I think we would have all been happy still. It was our little baby.

The legacy

The real impact of Mass Effect on fans and the games industry would slowly expand as the trilogy continued.

Hudson: I think it grew over time. As I was doing a press tour afterwards, I think people were reacting positively to it, but it still hadn't settled in that maybe this would be a game and IP that were lasting, and that people would come back to, and that it would be meaningful over time. Maybe that came later, once the other games came out, and more people tried the first one and realized that we were building a substantial series.

What we lacked in the volume of fans, we made up for with passionate fans

Derek Watts

Watts: Actually, thinking back, what we lacked in probably the volume of fans, we made up for with passionate fans. We didn't get the 20 million people, but what we did do is get a very passionate fan base. And I think that surprised me, not only how passionate they were, but how much effort they made in creating characters and understanding the story, and how many people's lives it changed.

Sim: Even the day before yesterday, I had a contractor here at my house, and we were just chit-chatting. He's like, ‘Oh, what do you do for a living?’ I mentioned I work from home. I told him video game sounds. He's like, ‘I love games, what games have you worked on?’ And I said, ‘Well, there's one game called Mass Effect, I guess that’s the biggest.’ He’s like, ‘One game? That’s one of the best games in the entire world.’ So I still get fanboys this many years later that just love it.

Hoyle: We get mentioned like, ‘Oh, I want to create a universe like Star Trek, Star Wars or Mass Effect.’ That's crazy that it gets lumped in with those kinds of things. So yeah, it's super impressive, and I do think it made an impact.

Watamaniuk: I think there are two aspects to the Mass Effect trilogy that raised the bar. There are technical innovations, like the dialogue wheel and whatnot. But I think that it also raised the bar in terms of quality of world-building, and characters that you could legitimately fall in love with.

Meer: It was the first game that a couple could play together, where one of them plays and the other person watches it like a movie. It seems that was the way a lot of people played it. I've had people who are big fans of Mass Effect, who said, ‘I didn't play it for years, but my partner played it, and I just watched the entire 40-50 hours.’

You need to have a Hollywood-quality story, you need to have amazing characters that come along on the journey with you

Preston Watamaniuk

Watamaniuk: You see now the amazing storytelling that you're getting out of games like The Last of Us Part II, and Kratos and Atreus, stuff like that. Those are just staples now. You need to have a Hollywood-quality story, you need to have amazing characters that come along on the journey with you, it can't just be the 80s action conceit where everyone is this who-cares throwaway character. Stories from 2006, you wouldn't be able to get away with it anymore. A 91 back then is like a 75 nowadays.

Welbourn: I think CD Projekt RED, their whole company feels like it wants to be Bioware, in a lot of ways. And they're doing great stuff like Cyberpunk, the Witcher series. To me they're one of the top studios right now.

Shanawany: We were aiming to create a franchise as well as a game. We wanted this to be the next Star Wars or Star Trek universe, something we could play in for decades. Basically, we would aim for the stars; and even if we only got part of the way there, then we would have at least gone farther than if we had aimed lower. And in the end, we succeeded. Mass Effect is its own universe.

Meer: Full credit to Jennifer [Hale] and Bioware, female Shepard is in a lot of ways a very groundbreaking character. Female Shepard set that standard of, ‘No, I'm not going to be wearing a skimpy version of the armor, I'm going to be wearing the same armor that the male version wears, and I'm going to have the same animations that the male character has.’ And so I think in many ways that was very influential. Fem-Shep is definitely a seminal video game character.

Hudson: I think the most rewarding thing is when people tell you about what it meant to them when they played it, even when it's just one person's story about how it impacted their life. Especially for a game like Mass Effect, where you can explore different versions of yourself, and different versions of what you could be through role-playing. That seems to have had an impact on people on a personal level, and that's really the most important thing.