What is DNS and how does it work?

DNS is the internet's digital phone book, and impacts your browsing performance, security, and which websites you can access.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

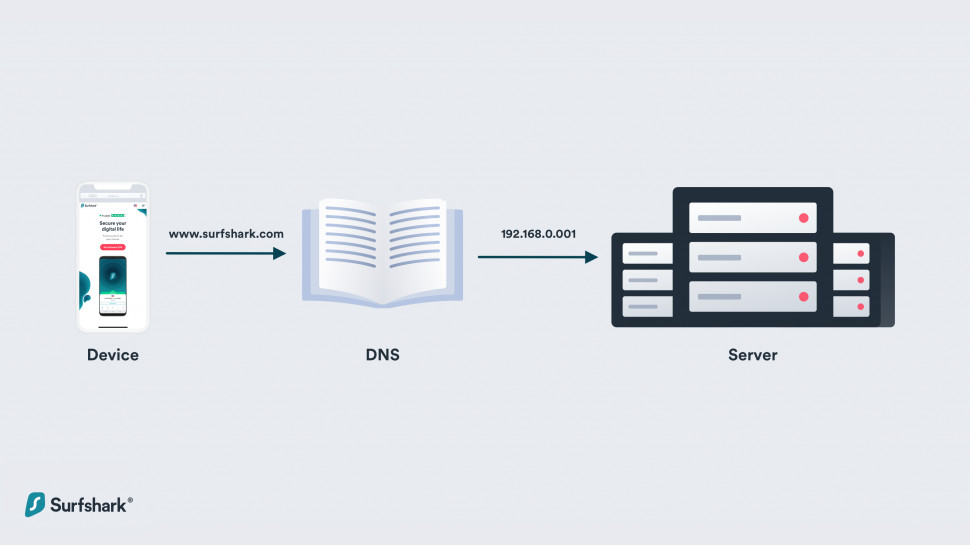

At first glance, the Domain Name System (DNS) might seem complicated, but if you think of it like the internet’s virtual telephone book, the picture gets a bit clearer. Everyone in the phone book has an assigned number and it’s the same with servers and devices—they each have their own unique internet protocol (IP) address.

When you type a website name into your address bar, your device uses DNS to look up its unique IP address and find the website. The IP address will look something like this: 212.100.66.113. Unless you have an awesome mind for numbers, or are part robot, IP addresses are hard to remember and sometimes change, which makes them less than ideal tools for navigating the web. So, DNS lets you punch in a readable domain (like techradar.com) and prompts your device to locate it with the accompanying string of numbers.

It’s a simple idea, but DNS has a huge impact on our digital lives. I’ll delve into detail about how DNS works, how it can influence your internet speeds, and the role it plays in your online privacy.

How does DNS work?

When you connect to the internet as usual, your internet service provider (ISP) will assign you two DNS servers—with one acting as a spare in case the primary server fails.

You might decide to search for a website by typing it into your address bar. When you, your device sends a query to the primary DNS server, which translates the domain into the associated IP address, which is how it finds the website you've requested. This translation process, from a familiar domain name to a robo-friendly IP address, happens every time you load a website.

Dig a little deeper into the process, and you’ll find that there are two kinds of DNS servers.

Recursive DNS server

Your search (or request) will reach the recursive server first. Then, it’ll look through recently cached web addresses (more on the caching process, later) to see if it can find the correct DNS record associated with the website you’re trying to load. If it can’t find these records, it’ll continue to make requests until, eventually, it either times out or returns an error.

Authoritative DNS server

Authoritative servers sit at the opposite end of the domain lookup process—they’re at the lowest point of the DNS chain. These servers provide the correct IP addresses to their recursive cousins so that your desired webpage can load.

The DNS process: step by step

Here’s a whistle-stop tour of what happens behind the digital scenes whenever you search for a website.

This sounds like an involved process, and it is, but it all happens in the blink of an eye. DNS resolvers speed up the process by caching DNS records, too, which means that there's less work to do when you want to return to the website in question.

A common internet myth claims that there are only 13 root DNS servers—and that they’re all located in the US. While there are only 13 IP addresses for root DNS currency, the number actually represents clusters of servers located around the world. As the internet transitions from IPV4 to IPV6, more root DNS IP addresses will become available.

What is DNS caching?

Simply put, DNS caching happens when a DNS server (the recursor) keeps hold of IP addresses and their matching domains. It’s how they speed up the lookup process—and keep loading times nice and short.

DNS queries are already surprisingly fast, however, even though there’s so much happening. Optimization and minimal bandwidth use mean that a fast DNS server (and one that’s nearby) can return an IP in less than 10 milliseconds.

Other DNS servers might take more than 100 milliseconds to do the same, however, and that’s when DNS speed begins to make a noticeable difference to your browsing experience.

It’s also worth noting that one website might load resources from multiple domains. If you access bigsite.com, for example, it might load images from one server, scripts from another, adverts from several providers, social networking buttons for every platform under the sun, and who knows what else.

This is why, at each stage of the DNS lookup process, the DNS recursor and root servers will try to save the IP address of domains for later use—so they can return them to you right away. This is caching in a nutshell.

Apps and devices can also reduce the impact of DNS queries by storing IP addresses in the cache, saving them for future connections.

On PCs, for example, DNS query results are stored by the browser and the operating system. Windows users can even check out a list of all cached domain names that the OS has stored by opening the command prompt and typing:

///CODE///ipconfig /displaydns///CODE///Some web browsers store IP addresses in a special cache for later use, too. This reduces the number of steps in the lookup process—when a request for a DNS record reaches the recursive server, it’ll check the browser cache first.

Input chrome://net-internals/#dns to check out your DNS cache.

Storing IP addresses in the browser cache can cause issues if the domains change their IP addresses, however, and websites will fail to load. Luckily, today’s most popular browsers include a feature that’ll let you clear the cache entirely—and sometimes it’s beneficial to do this, especially if you’re running into a lot of HTTP errors.

What is DNS filtering?

DNS servers are hugely powerful—they have full control over the websites you can access. If a server doesn’t want you to access a particular domain (for example, if the domain is included in a blocklist), it can filter out your request, return an error rather than an IP address, and you’ll effectively be barred from entry.

This kind of filtering is often a good idea, though. It can block malicious phishing websites and even restrict access to adult content, making it an integral part of a parental control setup. There are other ways to restrict access to these websites, of course, but DNS filtering doesn’t rely on software and will apply to all of the devices connected to your network.

Other uses of DNS filtering range from irritating to seriously scary:

Your school’s Wi-Fi network might block access to social media platforms and streaming websites—presumably to keep you focused on your work.

Repressive governments use DNS (and other network trickery) to keep their civilians away from information they’d prefer to keep under wraps. This is, unfortunately, why guides to using WhatsApp are so well-searched in China

There are privacy concerns, too. If whoever runs the DNS server knows who you are, and knows your IP address, it could keep a log of all the websites you visit to build up a detailed profile of your browsing habits and history.

Public Wi-Fi hotspots are notoriously unsecure, and crafty cybercriminals have been known to create fake (and eerily convincing) dupes, in the hopes that you’ll click and connect to them rather than the real hotspot offered by the cafe, hotel, or airport. A malicious hotspot operator might spot someone doing some online banking, redirect them to a fake website, and steal their financial information.

Be sure to stop by our guide to the best VPNs of 2026.

This is called ‘DNS spoofing’, ‘DNS hijacking’, or ‘DNS poisoning’. The Chinese government has resorted to spoofing to prevent people from loading forbidden domains and redirect them to ‘appropriate’ alternatives. In 2012, Skype’s domain was targeted by DNS spoofing, and Chinese users were redirected to a malicious version of the software that allowed government agents to listen in to their calls.

So, you might be wondering if there’s a way to fight back against irritating instances of DNS filtering—and spoofing. A virtual private network (VPN) can help out. Connect to a VPN and your DNS queries will be redirected through an encrypted tunnel before going on to the VPN server, and handled there. With no way to see what you’re doing, the network can’t block your access, and you’ll be free to go about your business without restrictions.

However, it’s worth noting that some VPNs don’t offer this as a service. They’ll encrypt your connection, but they might also let your DNS requests go through to your regular provider. That means it’s still possible for snoopers to identify which websites you visit and, potentially, redirect you to malicious ones—in the biz, this is known as a DNS leak.

Can I switch DNS servers?

You can indeed, and there are some awesome benefits to switching DNS provider.

Some DNS servers are optimized for speed. DNSPerf, a benchmarking website, lists 43 public DNS resolves with average query times ranging from 14 milliseconds to almost 140 milliseconds. If your server is at the bottom end of this list, you might want to choose a quicker alternative.

DNS servers can filter content to block ads, tracks, malicious phishing websites, and adult content, depending on your needs. This can come in handy if you’re looking for a way to keep all of the gadgets in your house secure, all at once, without having to install other software.

However, switching DNS servers isn’t a good idea for everyone. Some parental controls, antivirus features, and internet security apps already replace your DNS servers with their own, and switching to a different server can cause you to miss out on some of their protection.

DNS attacks

Unfortunately, one of the downsides to having an IP address that’s readily accessible is that public DNS servers are vulnerable to DNS attacks. One of the crudest forms is called a ‘flood’ or ‘denial of service’ attack, where hackers overwhelm a DNS server with queries. This prevents them from processing legitimate website requests from regular users—like your good self—and can slow your browsing to a grinding halt.

If cybercriminals go one step further and actually gain access to a DNS server, they can hijack domains, and redirect you to bogus websites when you enter a legitimate domain name into your search bar.

Fortunately, you don’t need to manage your own DNS server or network to avoid the worst of these threats. Be sure to keep your devices free from malware, and use one of the best ad blockers available today to prevent harmful content from loading. If you're serious about your digital security, and you should be, it’s well worth investing in the best antivirus software, too.

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

Mike is a lead security reviewer at Future, where he stress-tests VPNs, antivirus and more to find out which services are sure to keep you safe, and which are best avoided. Mike began his career as a lead software developer in the engineering world, where his creations were used by big-name companies from Rolls Royce to British Nuclear Fuels and British Aerospace. The early PC viruses caught Mike's attention, and he developed an interest in analyzing malware, and learning the low-level technical details of how Windows and network security work under the hood.

- River HartTech Software Editor