Why the internet of things needs eyes in the skies

The IoT’s infrastructure is slowly being sent into orbit

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

We may live in a global economy, but the internet of things (IoT) is not global – not even close. Only 2.7% of the world's land is urban, and even landmass only makes up 29.2% of the planet's total surface.

"Mainstream communication systems only cover a small fraction of the Earth," says Richard Traherne, Chief Commercial Officer, Cambridge Consultants, who says that mobile phone coverage extends over only 10% of the planet – and that's being generous.

"It will take many years before IoT technologies are rolled out to achieve the same level of coverage as mobile networks even," he adds. No wonder, then, that in a quest to create global services, IoT infrastructure is slowly being sent into orbit.

Why does the IoT need satellites?

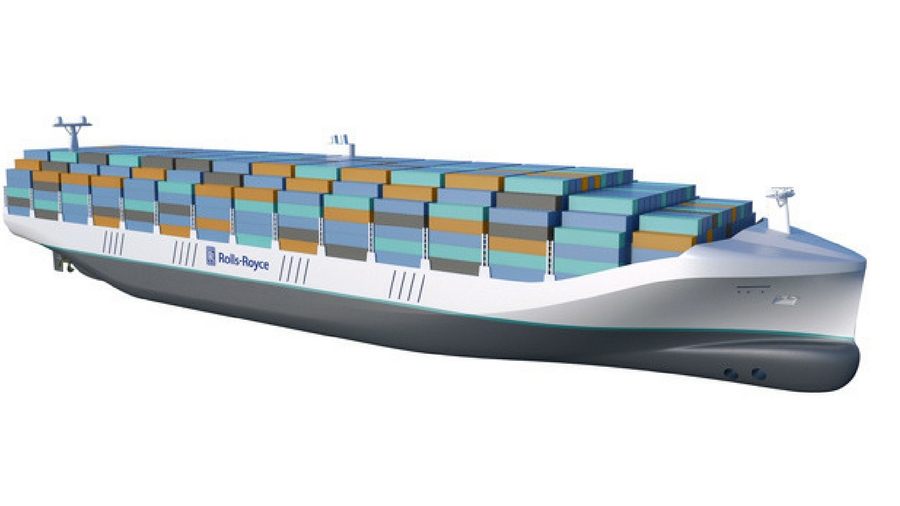

"IoT by satellite is an important part of IoT – it's intrinsically wide-area, low-power, and globally available," says Traherne. Any IoT project that requires wide area mobility and coverage – such as logistics on land, sea and air, asset monitoring (including oil, gas, electricity and water pipelines) and environmental monitoring – are key areas for IoT by satellite.

Cue satellites from Iridium and Inmarsat, although both are completely different in terms of technology and use-cases.

"For a long time we've been about voice, data and email with only some machine-to-machine (M2M) use-cases, but it's been fairly unsophisticated," says Paul Gudonis, President, Inmarsat Enterprise, which has just paired-up with Actility to deliver the world’s first global IoT network. "But over the last 12 months we've seen an explosion in companies wanting to get as much access to data as they can to drive efficiency – and much of it sits outside terrestrial coverage."

"Satellite links are used in cellular networks as backhaul technologies for remote areas or areas in which traditional backhaul technologies are unsuitable," says Traherne. Increasingly, satellite fleets are being integrated into the IoT as backhaul – the link between an LPWAN network and a backbone network – typically where cellular coverage is poor or non-existent.

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

What is Iridium?

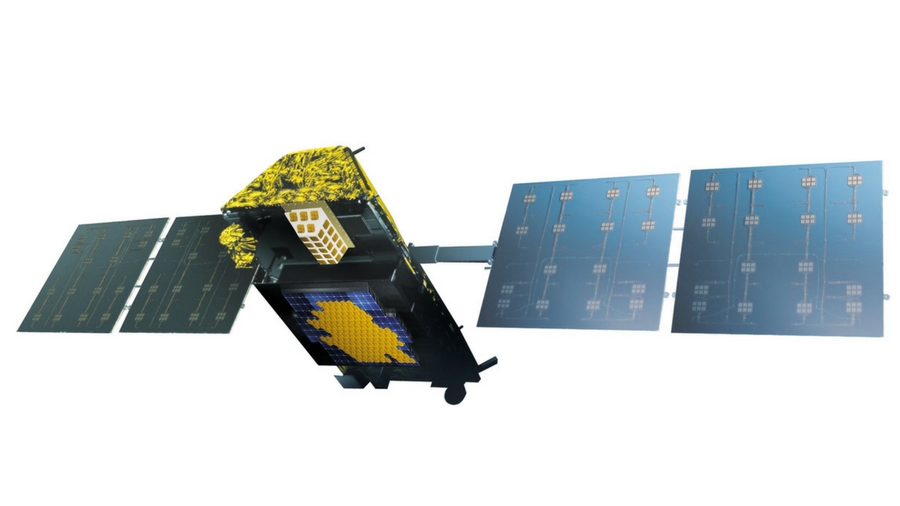

The Iridium system is a network of multiple Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites, 500 miles up in the sky, travelling at 17,000 miles per hour (you can watch one flash dramatically just after sunset if you keep an eye on this website). "LEO devices rely on the ever-moving network above them to provide coverage anywhere as long as they have a clear path to the sky," says Traherne.

SpaceX recently launched the first 10 of 70 satellites for Iridium (and landed the Falcon 9 rocket back on a drone-ship), which will add to its existing fleet of 66 satellites to create a $3 billion (around £2.4 billion, AU$3.9 billion) constellation called Iridium NEXT that's being described by some as the biggest tech refresh in the world right now. Iridium is paying SpaceX upwards of $500 million (around £400 million, AU$650 million) for seven launches.

"Iridium NEXT will extend Iridium's existing capability to provide higher speeds that unlock new possibilities in asset tracking, fleet management and other intelligent data applications," Traherne says. It could also bring mobile broadband to phone users in very remote areas. "Each satellite covers an area on the globe that's about the size of North America, and each coverage area overlaps so that there are no gaps in the coverage."

Put simply, Iridium covers the entire planet, so fills in the gaps left by mainstream cellular and LPWAN IoT networks.

Main image credit: Iridium

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),