Why is RAM so expensive right now? It's way more complicated than you think

Yes, AI is partly to blame for surging prices and DRAM shortages, but that's not the whole story

One of the largest memory manufacturers, Samsung, has reportedly doubled the cost of DDR5 RAM which will, of course, be passed on to consumers, much to the pleasure of Samsung shareholders (and rivals who will see it as a thumps up to print money). Samsung makes its own DDR modules as well as selling DDR chip to third party vendors (rivals to its own product range). SapphireTech, on the other hand, is urging consumers to avoid panic buying during the RAM crisis. Sapphire is a relatively minor player that is at the receiving end of the current memory kerfuffle. It sells graphics card, mini PCs and motherboards but no memory modules.

RAM used to be one of the easiest PC components to ignore. You picked a capacity that matched your needs and budget, checked the speed corresponded with your motherboard, bought what you needed, dropped it into your computer, and forgot all about it.

If you’ve been following the news lately, and I’m sure you have, you’ll know memory prices have surged so fast that RAM is now one of the most volatile and confusing parts of the entire PC market, and the effects are spreading well beyond desktop builds.

What appears to be a simple price spike is actually the result of several overlapping shifts in how memory is manufactured, for whom it’s made, and where manufacturers expect to generate revenue over the next few years.

On December 11th TrendForce - which owns RAM price marketplace Dramexchange - published a damning report that highlights how the rapid surge in RAM prices could impact smartphones more than laptops (and desktops one would expect).

On the latter platform, 8GB will remain the entry-level standard for the foreseeable future, a potential setback for Microsoft who advocated the move to 16GB to give Windows 11 a bit more wriggling room.

Entry level smartphones, which represent the bulk of new mobile handset sales, will most likely stay at 4GB, the same amount of memory one would find on cheap smartphones 10 years ago.

So, as a market observer, I'd say that the current situation set us back at least a decade in terms of affordability and innovation. The current RAM situation is going to negatively impact client-based AI as vendors cut down on RAM at almost all price points. Which - some cynics may say - is great news for hyperscalers.

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

Meanwhile Framework, an up-and-coming PC and laptop maker that has captured the minds of enthusiasts and prosumer, has confirmed it will increase the price of DDR5 memory upgrades by a shocking 50% as it simply cannot absorb the cost increase and has to pass it on to customers.

They have not however changed the price of the 128GB of the Framework Desktop which is one of the 30-odd devices that use the AMD Ryzen AI Max+ 395 APU - which comes with 128GB of RAM as standard.

Furthermore, Framework went to great lengths to explain how the amount of memory (RAM) used by a single data centre could equip more than one million laptops. For example, a single Nvidia GB300 rack can contain 37TB of a mix of HBM3E and LPDDR5X memory.

I can only applaud the level of transparency and the fact that they will take strict measures to prevent scalping.

Nirav Patel, the CEO of Framework said in a statement that "We are adjusting our return policy to prevent scalpers from purchasing DIY Edition laptops with memory and returning the laptop while keeping the memory. Laptop returns will also require the memory from the order to be returned".

AI makes waves

It's not the first time that prices on DRAM have shot up in such a away. Back in 1995, an earthquake in Kobe, Japan sent shockwaves in the memory markets with prices going up 30% within days. Another fire in 1993 in a resin factory in Japan also made buyers and investors very nervous as resin is a vital material in building DRAM modules.

At the center of the problem is DRAM, the type of memory used in PCs, laptops, phones, consoles, servers, and cars. Although most people just call it RAM, nearly all modern system memory is DRAM, including DDR4, DDR5, LPDDR, GDDR, and HBM.

Those different formats serve different roles, but they come from the same production ecosystem, and that is controlled by just three memory giants: SK Hynix, Samsung, and Micron. Together they account for more than 90% of the total random-access-memory (RAM) market (Counterpoint, October 2025).

All three happen to be major players in NAND as well, the building block of SSDs.

There are a handful of other DRAM players: CXMT, Nanya being the two main ones with smaller brands located in mainland China.

For years, that concentration didn’t feel like it was a problem as production was steady, demand was predictable, and price swings were usually gradual enough for consumers and OEMs to plan around. Prices went up, they went down. If you needed some more RAM and weren’t in a rush, you could wait for a Black Friday deal.

That all started to change before most people even noticed. Well before the AI boom reached the crazy heights it’s at now, DRAM makers were already preparing for a transition away from older memory types.

DDR4 and LPDDR4 were built on aging process nodes that manufacturers wanted to retire. Those older nodes were less profitable and blocked capacity that could be used for newer, higher-margin products.

Micron and others issued end of life notices for several DDR4 and LPDDR4 parts, pushing customers to secure supply while they still could. That had the knock on of creating early shortages and price spikes in memory that should have been getting cheaper.

Then AI spending exploded.

Consumer RAM loses its appeal

Training large models and running inference at scale requires huge pools of fast memory, and not just storage. GPUs used for AI rely heavily on High Bandwidth Memory, which is still DRAM, just stacked vertically and tuned for extreme throughput.

Every wafer that goes into HBM is a wafer that can’t be used for standard DDR5, LPDDR5X, or GDDR6. Once hyperscalers and AI firms started signing massive contracts, memory makers inevitably followed the demand... and the money.

HBM and server DDR5 offered long term deals, predictable volume, and far better margins than selling consumer DIMMs through retail channels. Consumer memory didn’t disappear overnight, of course, but it stopped being the priority, something that is clearly visible in today's pricing.

DDR5 kits for PCs that sold for reasonable prices only months ago are now listed at amounts that feel closer to high end GPUs than the supporting components they are. (There are deals to be found, but they are becoming increasingly rare).

Even individual DRAM chips traded on the spot market have multiplied in price over a short span, reflecting panic buying and constrained supply rather than organic consumer demand.

Spot prices refer to short term trades of individual chips between suppliers and buyers, not the finished sticks people buy for PCs. Contract prices reflect longer term agreements between manufacturers and OEMs.

When both move sharply upward at the same time, it’s a sign that supply is tight across the board and that no segment is insulated. And that’s exactly what’s happening now, as you can see at DRAMeXchange.

Contract prices for notebook memory have jumped by double-digit percentages in a single quarter. Spot prices for common DDR5 chips have risen several times faster than typical seasonal fluctuations.

Even older RAM types like DDR3 and DDR4, which should be going gentle into that good night, are getting more expensive as supply is cut faster than demand fades. The result is a market where nothing feels especially safe, let alone cheap.

A Crucial problem

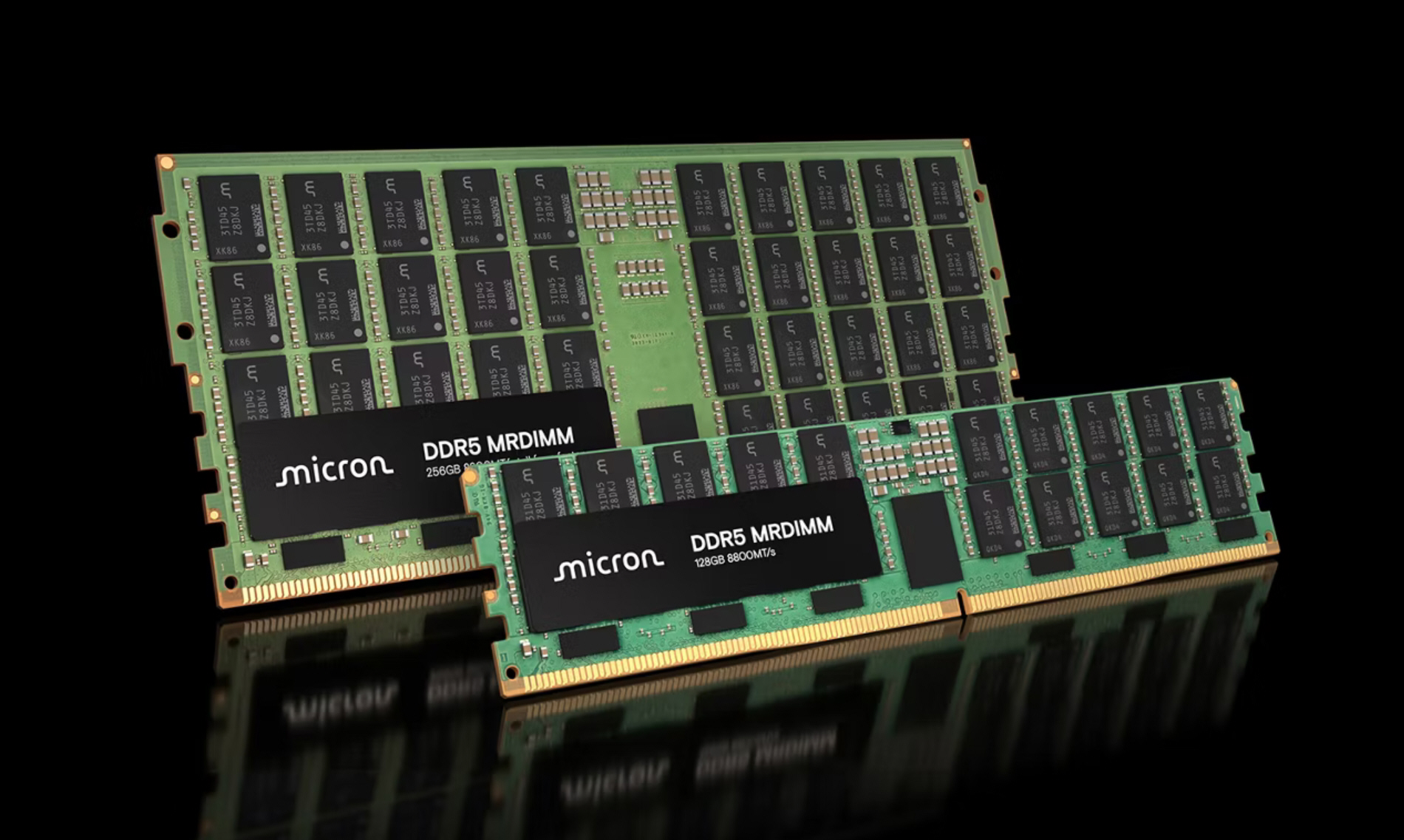

Then when things were looking bad for consumers, Micron made them much worse by announcing plans to exit the consumer memory and storage market, killing production of its Crucial branded RAM and SSDs.

Crucial was one of the few consumer facing arms of a major DRAM manufacturer, often acting as a price anchor that kept competitors in check. Many of the PCs I’ve built or upgraded over the years have had Crucial RAM. The desktop beast I’m writing this on still does.

Explaining its decision, Micron said: “The AI-driven growth in the data center has led to a surge in demand for memory and storage. Micron has made the difficult decision to exit the Crucial consumer business in order to improve supply and support for our larger, strategic customers in faster-growing segments.”

Micron will continue shipping Crucial products until February 2026, but after that, the brand will become a distant, much loved memory.

In practical terms, this leaves Samsung and SK Hynix as the only major suppliers feeding the consumer DRAM market at scale and as most people know, less competition almost always means higher prices, especially when demand elsewhere is stronger.

Samsung’s recent strategy shows how distorted the incentives have become. Facing intense competition in HBM, where SK Hynix has led for several generations, Samsung reportedly shifted large chunks of DRAM production toward DDR5 RDIMM modules.

These are server memory sticks, not consumer DIMMs, and they currently offer huge margins. Contract pricing for high capacity DDR5 RDIMMs has climbed to levels that make them more profitable than HBM, without the same technical risk or certification hurdles.

Spot prices have gone even higher, suggesting – oh joy! – there’s further room for yet more increases.

From Samsung’s perspective, allocating wafers to DDR5 server memory instead of discounted HBM or consumer DDR5 makes financial sense. From a consumer perspective, however, it means less supply and higher prices across the rest of the market.

SK Hynix has said it plans to ramp DRAM production in 2026, but most of that output is inevitably aimed at AI and enterprise customers. Very little of it is expected to relieve the pressure on consumer PCs, and certainly not in the near term.

The knock-on effects are spreading quickly. Graphics cards rely on GDDR memory, which comes from the same manufacturers. As DRAM capacity tightens, GDDR6 pricing is climbing, pushing costs up for mid range and entry level GPUs. Mobile devices use LPDDR, and those parts are seeing steady increases that phone makers will eventually pass on.

Storage isn’t immune either. NAND flash, used in SSDs and memory cards, is also being pulled toward enterprise and AI workloads. Contract demand for NAND wafers has surged, and consumer SSD prices are starting to creep upward after a long period of decline.

Preparing for what comes next

Not too worried yet? You should be. OEMs are already preparing customers for what comes next. TrendForce reports Dell is planning double digit PC price increases and Lenovo has warned that existing quotes won’t hold. HP has said that if memory conditions don’t improve, the second half of 2026 could bring even higher system prices.

This isn’t just about enthusiasts paying more for upgrades either, as it affects schools buying laptops, businesses refreshing fleets, and anyone relying on what should be affordable hardware.

There are ideas for easing the pressure of course, but none are simple. One approach gaining attention in data centers is memory expansion over CXL.

As we reported here, devices like Marvell’s Structera cards allow operators to attach pools of older DDR4 memory to servers over PCIe, effectively reusing retired modules. Compression can stretch capacity even further, turning existing hardware into a larger usable pool, and reducing the need to buy new DDR5 - at least for certain workloads.

It doesn’t help consumers directly, but it could slow enterprise demand enough to free up some supply.

The longer term fix is new fabrication capacity, but building a DRAM fab costs billions and takes years. Micron has announced a $10 billion investment in a new facility in Japan, but it isn’t expected to produce chips until at least the second half of 2028.

Samsung and SK Hynix, ahead of the curve as always, have their own expansion plans, but none of them will offer quick relief.

The other way out of the current mess relies on memory demand cooling. If AI spending slows, or the economics of large scale training change, the rush for memory could ease.

That would leave manufacturers with excess capacity and drive prices back down, just as has happened after past boom cycles. But betting on that outcome means betting on a shift in one of the largest investment waves the tech industry has ever seen. AI might be a bubble, as a number of analysts have claimed, but for now, the trajectory points the other way.

Memory makers are being rewarded for serving AI and enterprise customers, older standards are being retired faster than demand disappears and consumer brands are shrinking, not growing.

Prices are rising not because everyone suddenly needs more RAM at home, but because the same factories are feeding a very different kind of customer. RAM has gone from commodity to constraint and until supply, demand, and priorities change, it’s very likely to stay that way.

Follow TechRadar on Google News and add us as a preferred source to get our expert news, reviews, and opinion in your feeds. Make sure to click the Follow button!

And of course you can also follow TechRadar on TikTok for news, reviews, unboxings in video form, and get regular updates from us on WhatsApp too.

Wayne Williams is a freelancer writing news for TechRadar Pro. He has been writing about computers, technology, and the web for 30 years. In that time he wrote for most of the UK’s PC magazines, and launched, edited and published a number of them too.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.