Like a Dragon: Infinite Wealth has some big points to make about poverty, justice, and environmentalism

Shining a light

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

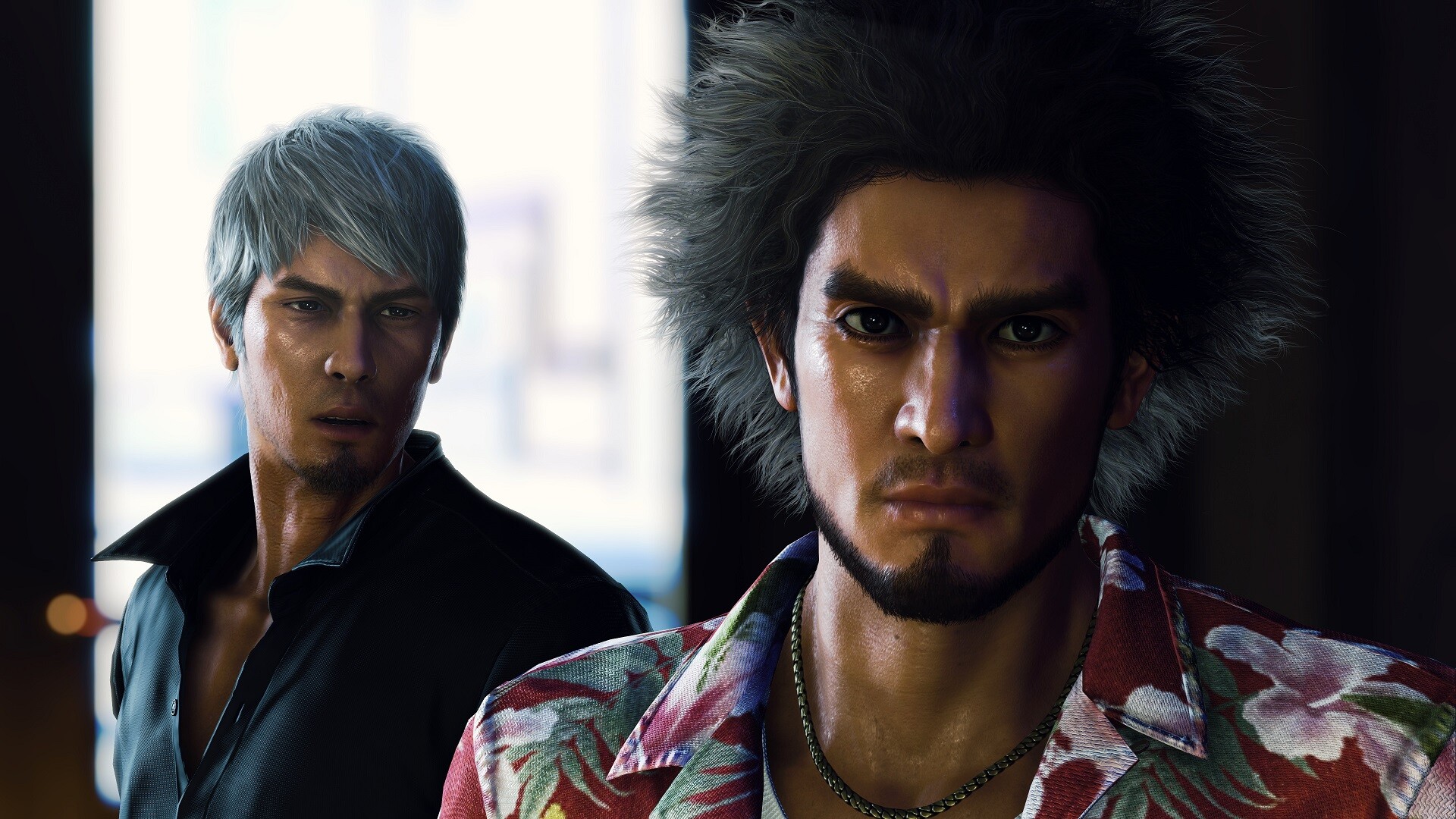

Like a Dragon: Infinite Wealth encapsulates a mind-boggling range of tones and themes. In Ryo Ga Gotoku Studio’s modern-day role-playing game (RPG), you can find yourself held at gunpoint one moment and in a wholesome karaoke montage the next. That said, this latest entry in the long-running Yakuza series never shies away from seriousness and gravity when the situation calls for it - which is surprisingly often.

Throughout protagonists Ichiban Kasuga and Kazuma Kiryu’s journey across Hawaii and Japan, Like a Dragon: Infinite Wealth shines a light on some dark and challenging themes with nuance and even-handedness worthy of the very best story games. From socio-economic inequality to issues of environmentalism and justice, Ryo Ga Gotoku takes great pains to place its story in the context of the modern world. Nothing that Kasuga and Kiryu do takes place in a political or social vacuum.

Minor spoilers follow for Like a Dragon: Infinite Wealth

In a refreshing turn for a game that’s about the criminal underworld, Like a Dragon: Infinite Wealth spends much of its early chapters directly confronting the cycles of social stigma and poverty that keep criminals turning to crime. Though the noble-hearted Kasuga is able to get a legitimate job at the employment agency Hello Work, he fights an uphill battle to help other ex-Yakuza find stable (non-illegal) work of their own.

Despite Kasuga’s best intentions, he is eventually framed for corruption by a VTuber (virtual YouTuber) who uses Kasuga’s past criminal connections to incriminate him as part of a wider plot. Even for our hero with a heart of gold, his criminal past is still used against him to stigmatize his present actions.

Tip of the iceberg

However, Infinite Wealth doesn’t just focus on the struggles of our protagonist. Rather, it confronts the systematic issues faced by those convicted of criminal charges. Stigma against ex-convicts is widespread, both in the United States and in Japan, often leading to low rates of employment and high rates of reoffence. In the US, an estimated 60% of ex-convicts remain unemployed a year after their release (via the New York Times).

Japan faces similar issues. As director Atsushi Funahashi put it when talking about his docudrama Burden of the Past: “Ex-convicts are pushed to the corner of society [...] nobody is there for them. They don’t have a job, and they have no place they can live because of social prejudice” (via Japan Times). This sad fact is, in part, why the reoffense rate in Japan stands at roughly 50% for ex-convicts.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Ex-cons struggle to get work due to social stigma, which leaves them vulnerable to exploitation

Acting on the wishes of his deceased mentor and father figure, Kasuga spends Infinite Wealth’s prologue struggling to help other ex-criminals make an honest living. The ‘five-year clause’ which prevents ex-Yakuza from opening bank accounts provides a significant hurdle for those looking to get on the straight and narrow, meaning that Kasuga has to occasionally get creative by opening phone contracts and accounts himself as a proxy for the ex-criminals he’s attempting to help.

This problem is especially significant since Infinite Wealth takes place shortly after The Great Dissolution - an event in the game’s fiction where the Tojo Clan and the Omi Alliance formally ceased their criminal operations, ending the careers of thousands of Yakuza - all of whom now find the odds stacked against them.

Much like in real life, in Infinite Wealth, ex-cons struggle to get work due to social stigma, which leaves them vulnerable to exploitation by criminal groups - a process that often leads to repeat offenses. In addressing these themes head-on, Ryu Ga Gotoku asks eye-opening, essential questions about the nature of justice, suggesting that a restorative model does more good than a more punitive approach.

Vicious cycles

When investigating Hawaii in search of his long-lost biological mother, Ichiban Kasuga volunteers with Palekana - a religious community group that runs an orphanage as well as a food bank. When helping out at the food bank, one of the Palekana followers opens up to Kasuga about the high cost of living in the state and how it drives up homelessness and poverty. “Hawaii’s inflation gets worse every year,” he says. “The rent being worst of all. An average family pays $3,000 a month just to live in a tiny apartment.”

“I guess reality hits hard even in paradise,” responds Kasuga.

Hawaii has the highest percentage of homeless people in the US by state, according to a report from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development in 2023. This issue is, in part, caused by the effect of tourism on housing affordability, which drives up prices. According to a report from Stanford University, the cost of housing is 149% over the US average, and the State has a cost of living that stands at 65.7% higher than the rest of the nation.

Like a Dragon: Infinite Wealth isn’t getting its plot points out of nowhere. The struggles and hardships explored by the game are all reflected in our own reality. One of the game’s major criminal factions, the Barracudas, specifically exploits homeless people, swelling its ranks with desperate individuals who have nowhere else to go.

Towards a greener world

Wearing its heart on its sleeve, Infinite Wealth has a strong environmentalist message, too.

Perhaps the most ambitious Yakuza minigame to date, Dondoko Island gives you your own slice of paradise. Much in the same way as the likes of Stardew Valley or Animal Crossing: New Horizons, you’re expected to grow and develop your island, building a resort over in-game weeks by gathering resources and crafting furnishings.

However, when we arrive at Dondoko island, we see it covered in trash, dumped by the Washbucklers - a gang of criminals who illegally dump waste on the island. Rather than just building a resort, Dondoko is about re-naturalizing the island in a sustainable and eco-friendly way.

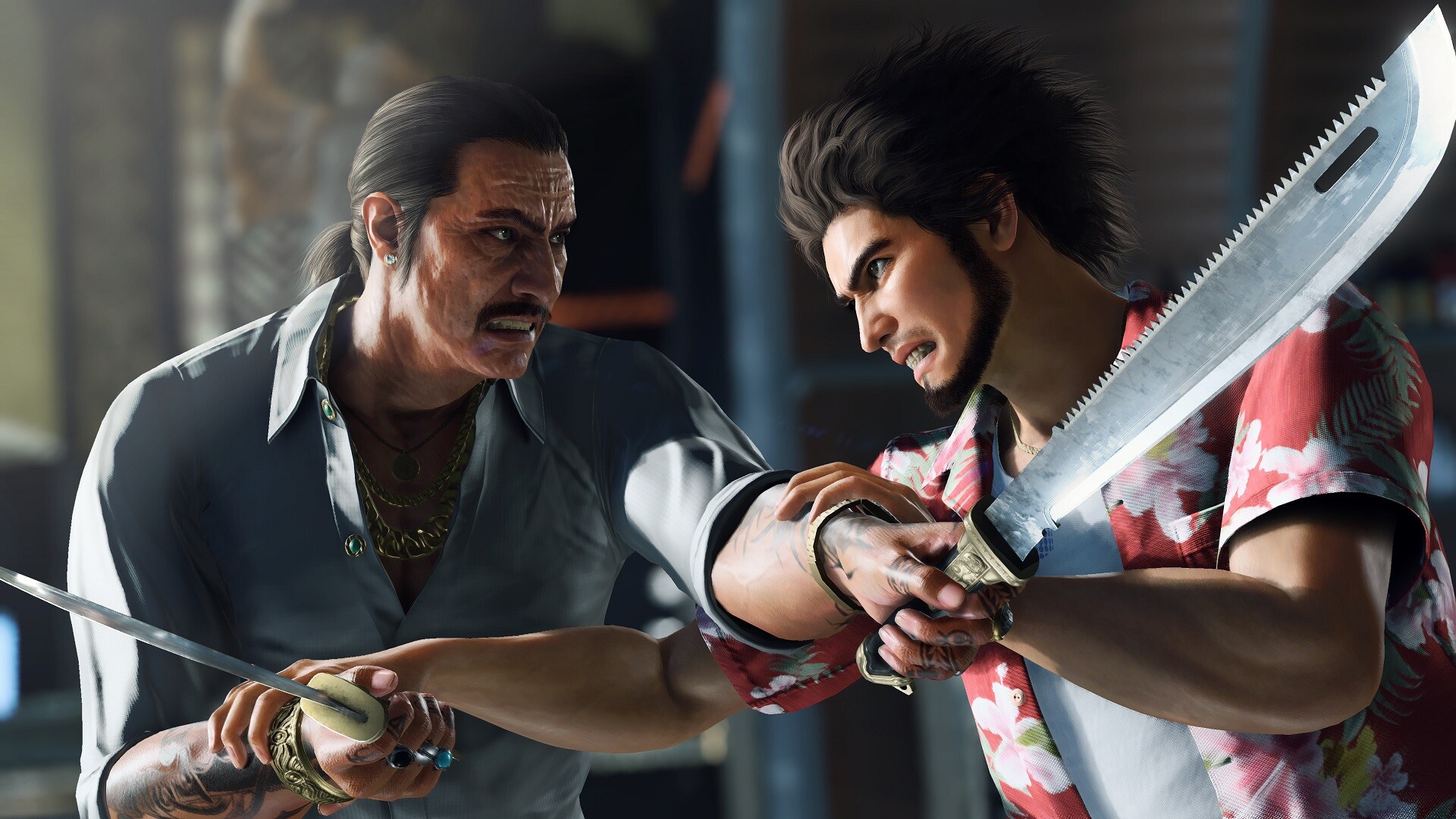

The ethics of nuclear waste dumping is explored in Infinite Wealth’s latter chapters

The game’s main plotline also leans heavily into environmental themes, too, beyond Dondoko Island's subplot. Not only does Kasuga help Palekana with a beach cleanup early on in the game, but the overarching plot also concerns the dumping of nuclear waste. I don’t want to give too much away here, but the ethics and accountability of waste dumping are both thoroughly explored in Infinite Wealth’s latter chapters.

Infinite Wealth’s portrayals of economic hardship, cycles of stigmatization, and the ecological issues facing the modern world are as relevant as they are poignant. By refusing to shy away from these troubles, Ryu Ga Gotoku grounds its story and characters in a rich bedrock of believability. The RPG may be fiction, but the struggles it portrays are very real.

For more thought-provoking titles, check out our lists of the best RPGs and the best single-player games.

An editor and freelance journalist, Cat Bussell has been writing about video games for more than four years and, frankly, she’s developed a taste for it. As seen on TechRadar, Technopedia, The Gamer, Wargamer, and SUPERJUMP, Cat’s reviews, features, and guides are lovingly curated for your reading pleasure.

A Cambridge graduate, recovering bartender, and Cloud Strife enjoyer, Cat’s foremost mission is to bring you the best coverage she can, whether that’s through helpful guides, even-handed reviews, or thought-provoking features. She’s interviewed indie darlings, triple-A greats, and legendary voice actors, all to help you get closer to the action. When she’s not writing, Cat can be found sticking her neck into a fresh RPG or running yet another Dungeons & Dragons game.