'The challenge is educating people:' Element's quest to encrypt remote workspaces

Matrix just hit 115 million users as it announces its latest revamp

Computer scientists Matthew Hodgson and Amandine Le Pape came up with the idea of Matrix—an open-source protocol for decentralized and secure communications—back in 2013. Four years later, Element was born as the first UK-based encrypted communication and collaboration platform. Harnessing the power of Matrix, the service seeks to give both individuals and organizations a new sense of security and agency over their data.

Now, after nine years, Matrix has surpassed 115 million active users—almost doubling its user base over the last 12 months. The Element app is currently being used by many governmental and public bodies, as well as larger organizations and privacy-concerned individuals looking for deeper customization options that similar encrypted messaging apps often lack.

With remote and hybrid work gaining popularity, Hodgson and Le Pape knew they needed to improve Element's usability to attract even the tech newbies out there. As a recent study from Forrester Consulting (commissioned by Element) shows, despite secure messaging solutions being in huge demand, more than half of respondents still use unsanctioned consumer-grade apps for enterprise communications. It's in this context that Matrix 2.0 was launched.

Since announcing the idea of Matrix 2.0 at FOSDEM, we've been busy building out full real-world implementations for folks to play with, and today we're super excited to take the wraps off Matrix 2.0: The Future of Matrix. https://t.co/wBc3wrgSZl 👀🎉🎊🍾👀September 21, 2023

Matrix's revamp includes a new API to make the login, launch, and sync process instant—the company now claims to outperform the biggest names out there such as iMessage, WhatsApp, and Telegram on this front. Other features include native OpenID Connect and native Group VoIP for maximum security.

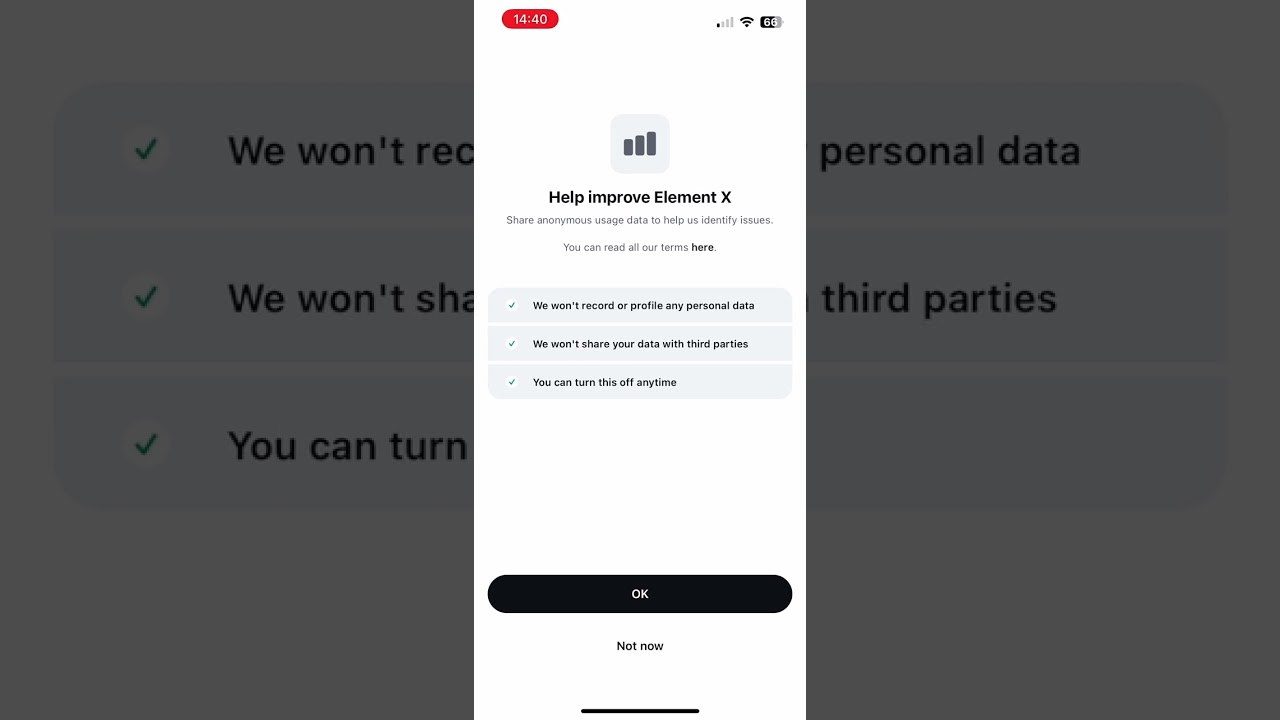

A new encryption protocol deserved an app that could really help it shine, though. That's why Element X was developed. The provider described this as "a super-fast stripped-down messenger which serves as a preview of a complete rewrite of the full Element app for secure collaboration and messaging due next year."

On the occasion of this launch, and with new cyber threats to businesses looming in the background, I talked with Hodgson to understand what's in store for the future of secure communications across enterprises in the UK and beyond. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Could you tell me a bit more about Element's latest updates?

Historically, privacy preserving communication tools have not had the best usability. In the early days, they were very much built by geeks like me, for geeks like me. In the last 6 months, we've seen a steep change in that on the Element site. We have put out Element X, which is an entirely new generation of our mobile apps that outperforms iMessage, WhatsApp, Signal, and Teams, after an awful lot of effort in going and building an entirely new approach on Rust to get the performance and usability high enough. I'm really excited that we've turned the corner on that.

It's been nine years coming, but finally, we have an app out there that I think is 4.9 stars on the app store. In terms of people's reaction, the app being properly usable gives me a lot of confidence that people will no longer be able to say, 'Oh, encrypted apps are a bit hard to use.' That's personally what I'm most excited about now that we have a really glossy usable app in the wings which will hopefully empower users and companies to have proper security as well as a great experience.

This also coincided with Matrix 2.0, which is the underlying protocol updates that we did in order to get instant launch, instant sync, instant log in, and really get the thing as snappy as you would expect from something like iMessage. The app is still in development and currently usable by existing Matrix users. We're just playing catch-up on the feature.

Which are the biggest challenges to the future of secure communication across businesses?

The biggest challenge is educating the world on the importance of encrypted communication. It's strange that people understand it for personal communications, but in the workplace, people seem to be much less worried. That's really surprising as we see more and more data breaches happening, including in larger organizations. They are accidentally leaking their own internal chat history to the Internet because it's all just sitting there unencrypted on their servers.

I would assume that any competent nation State attacker could have broken into the infrastructure of someone like Microsoft, or Slack, and be gathering up that unencrypted data. The potential embarrassment and chaos could be catastrophic. It's not implausible at all to imagine that the risk of having the unencrypted data all stacking up is a time bomb—a very vicious time bomb—waiting to go off.

So the biggest challenge I see is educating people, outside of the public sector and defense and across other industries like healthcare, about the importance of actually keeping conversations private. Otherwise, the level of potential embarrassment when it gets breached and leaked is potentially catastrophic.

What do you think is the reason behind this lack of education?

I think it might be inertia and the fact that, particularly during COVID-19, lots of organizations had never spoken online before. They didn't have chat systems. They used email, they had phone calls, or they just met in person. Then, suddenly they had no choice but to work remotely.

I think they had a choice. Either doing the right thing and finding a more unusual cutting-edge tool like Elements or Matrix to securely communicate, and some of them did. Or, you just look to see what everyone else is doing. And, if everybody is suddenly thundering onto Teams because they already have Windows PCs, use Office 365, and get Teams for free, then there is a herd mentality that if I'm a CEO somewhere I'm not gonna get fired for buying more stuff from Microsoft.

So, even though from an information security perspective, it's a disaster in the making, there is an assumption that you can't go wrong buying from the biggest tech company in the world.

Could Big Tech firms have done something differently to fix this issue?

You could have seen the same thing happen on consumer chat if the guys at Signal hadn't worked with WhatsApp to set a precedent for privacy. With the biggest chat system being encrypted, everybody else felt competitive pressure to keep up. So, similarly, Microsoft could have chosen to take a principled stance and tackle the much harder problem of encrypting everything by default. Then, it would just be part of the ambient default for the industry. But they didn't. So, the opposite has happened.

Encryption ends up being the exotic edge case with a handful of smaller vendors like us who have taken the effort to build it in. Meanwhile, the big guys are kind of vaguely trying to make it happen.

I think they are also concerned, perhaps, about liability. Like, what if one of their customers goes and stores illegal material, and if it's encrypted, what would Microsoft's lawyers say then? Right now, they know precisely which data is on their service because it's all unencrypted. Also, there's a risk of abuse because adding it in later is hard. We've seen both Slack and Microsoft start to try to add it on, but doing it in a way that still lets the organization hierarchy monitor for abuse. Auto capability is a really hard thing to stick on.

Are there some specific sectors, or even countries, that are worse than others?

The UK is really bad. It's weird, it's worse than the US for whatever reason. We did a government conference the other week and almost everybody we spoke to was on Teams for really sensitive departments. Without embarrassing them by naming them, they're the sort of people whose chat history would be incredibly, politically and socially sensitive if it leaked.

So the UK is particularly bad, and Germany is particularly good. I guess they have more first-hand experience of the risks of privacy breaches due to surveillance technology from all ends of the political spectrum. At the beginning of COVID, I recall that Microsoft offered the Government a huge incentive to use Teams, and they pushed back and said they would rather build and use their own self-sovereign secure communication. That's when we started to work with them on rolling out Matrix for the military. And now BundesMessenger is the Federal encrypted chat system. It took longer to get there, but now they have communication services that they run themselves in their own geography, and they are end-to-end encrypted. So, even if the servers get breached, the history is not going to be compromised.

We also see good interest in France, Sweden, and almost all European countries. There is also a concern about the risks of putting all of your data unencrypted into a big tech company. I'd say the US is kind of in the middle, Europe as a whole is in a good place, and the UK is in a particularly bad place.

What's Element doing about it? Are you trying to raise awareness across these bigger companies as well?

Yeah, absolutely. The Forrester report, The Future of Secure Communication, is there to help educate the industry as a whole and explain that there is a very viable set of solutions out there now for having proper secure communication for enterprises.

In the early days, you had to compromise on usability or features because it's really hard to rebuild these features in a privacy-respecting fashion. The classic example is search, where normally when you search, you rely on the server being able to see your data so that you can search for it on the server. But you have to do something else if the server cannot see your data. Either you have to do a very exotic fully homomorphic encryption approach, which is frankly still science-fiction. In reality, you end up shoving hundreds of megabytes of data around just to search for a basic term. Or, you search client-side—and that's what we do.

For instance—it's not rolled out on all platforms, but certainly on our desktop app—the app sits in the background, indexing your conversations and making sure that you can search the encrypted history, because the client can see you have to build that in from the answer.

In the past, that was a limitation. Now we have search and all the other features you'd expect, so it's really trying to educate and reassure the wider audience that you don't have to sacrifice usability or features.

How's Element preparing for a post-quantum world?

What we've done is to build some protocol agility into Matrix from the outset. According to its model, every single component can be switched out and, as long as the organization defining the spec and the feature set from the user perspective remain similar, it's still called Matrix. We're actually under the hood on version 11 of the protocol, and sometimes the changes have been significant.

We have another initiative called MLS, which is using the IETF standard for encryption, and we have another initiative which is post-quantum key exchange led on top of the existing encryption. It's surprisingly hard because you need to think ahead to everything that could be swapped out and make sure that it can be swapped out. We got it wrong in some instances, and it took us years to build the infrastructure to allow particular bits of the system to be modular.

But, by this point, everything has that modularity. Indeed, we're working with some of the big quantum experts because we're not quantum cryptographers, but we will very happily go and work with the actual academics to swap those primitives in a very similar manner to what Signal did a few weeks ago with their new post-quantum Diffie-Hellman exchange. It's slightly sad that they got there first, but competition is good.

Our quantum-resistant protocol upgrade, PQXDH, is now “the first machine-checked post-quantum security proof of a real-world cryptographic protocol.”Thanks to the researchers who did this important formal verification! Read more from them here👇https://t.co/vp1sX81tJ7October 20, 2023

And what about AI? Do you think is it a threat for secure communication as well?

In a kind of naïve approach, the way people are using AI today is incredibly privacy-violating. I think Signal described it as a fundamentally privacy-antagonistic technology. I'm a little bit more neutral because I think, as a technology, it could be very valuable and powerful. But as a user, I need to be able to control whether my stuff is trained on it and how I expose my conversations to it.

Just like Search, our solution to this is to run a client-side. Luckily, the power that you get in your modern phones is enough to do quite a good job of running a very complicated AI model client-side so that you don't need to expose the data to the server. You do, however, need to download gigabytes of data for the model onto your phone. You have to find a responsible place to exhaust that model. That's currently a very open question, because all the current models are trained haphazardly on anything that is found on the Internet.

We believe that there may be a kind of happy ground where you can empower the user to control the data and still get the benefits whilst actually preserving data privacy. That's something that we're actively working on.

With proposed laws like the EU Media Freedom Act trying to regulate some use cases for spyware, how could secure communication exist at all in the future?

This is the weakness of end-to-end encryption. It works well protecting the server and the server data from being compromised, but if there is a legitimized way to spy on users on their client, it doesn't matter if the data is encrypted on the wire and on the server.

I think it's another angle of the war on encryption that we're seeing—I guess the third iteration of the Crypto wars. I had hoped this all finished about 20 years ago, but we obviously had the battle for the existence of TLS and SSL. Then, we had the battle for PGP and end-to-end encryption. Now, it's all happening again with this battle for client-side scanning and client-side spyware as a legitimized way to work around end-to-end encryption. It's a risk.

I really hope the legislation will come in to ensure that spyware is not in any way legitimized. If it is, then I can only hope that an immune response will happen—like people building technological solutions to fight against spyware. A good example is Apple with their Lockdown mode in iOS, which is deliberately built to harden things against NSO-style Pegasus malware attacks.

It's not dissimilar to the Online Safety Bill's scanning capabilities, just coming from a different angle. Every time there is a legal precedent to allow a privacy-violating technology to be inserted, even if initially it's looking for reasonable stuff such as preventing child abuse or some kind of cyberattack, the same mechanism can obviously be exploited by a corrupt user or an attacker. It acts as a precedent to show that you can start inserting potentially malicious technology. From a legal precedent, as we all know, that's incredibly dangerous.

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

Chiara is a multimedia journalist committed to covering stories to help promote the rights and denounce the abuses of the digital side of life – wherever cybersecurity, markets, and politics tangle up. She believes an open, uncensored, and private internet is a basic human need and wants to use her knowledge of VPNs to help readers take back control. She writes news, interviews, and analysis on data privacy, online censorship, digital rights, tech policies, and security software, with a special focus on VPNs, for TechRadar and TechRadar Pro. Got a story, tip-off, or something tech-interesting to say? Reach out to chiara.castro@futurenet.com