The secret world of video game age ratings and banning games, according to the Games Rating Authority’s director general

Aged like a fine wine

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The process of age rating games isn’t something I’d previously given a great deal of thought to, despite it being an intrinsic part of gaming.

We see age ratings constantly, on game advertisements, boxes, posters, and more. While they exist primarily to advise consumers about the content of games (particularly for parents and guardians buying games for their children), there’s always a general level of intrigue around ratings prior to a game's release, too, particularly if they're unexpectedly high. Sometimes, those mysteries can even persist post-launch. What did Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order do to justify a PEGI 16, for example? TechRadar Gaming discussed this, the process behind rating and banning games, and more, with Ian Rice, the director general of the Games Rating Authority, during an interview at WASD x IGN.

“The Games Rating Authority has been around for a very, very long time, doing things arguably a bit too quietly in the background,” Rice tells me. As of 2023, the Games Rating Authority (originally known as the Video Standards Council) is the sole authority in the United Kingdom responsible for using the PEGI (Pan-European Game Information) age rating system, which replaced the older European Leisure Software Publishers Association (ELSPA) system in 2003. The process is relatively straightforward and ultimately leads to games being given licenses to be legally sold in the UK, but it varies slightly between physical and digital games.

Article continues belowFor digital games and apps, the sheer quantity of releases calls for a streamlined approach. When publishers submit their products to digital storefronts, they fill out an International Age Rating Coalition (IARC) questionnaire, which asks a series of questions about content that relate to the classification criteria of all participating rating boards from around the world. Filling this out grants a full license, and IARC administrators then work to manually scrutinize a cross-section of everything, generally based on the number of downloads they have and using keyword searches for popular phrases.

Testing, testing

The IARC questionnaire is incredibly thorough - Rice sets me loose on it, to have a go filling it out for a game I know like the back of my hand, Xenoblade Chronicles. Many of the questions are what you’d expect - does the game show violence towards people or creatures? Is any blood shown? Is there any sexual activity? Some questions are a little more niche, though, including one that checks if any swastikas are shown. I firmly tick ‘no’. A few questions later, I’m greeted with an accurate ‘PEGI 12’ rating, as well as ratings for a plethora of other systems from across the globe.

For physical releases, the process differs slightly and developers fill out a similar questionnaire, which is then submitted alongside detailed written answers and a video compilation of ‘evidence’, demonstrating the content described, and, in theory, declaring everything that could possibly be contentious. At this point, a provisional age rating (complete with content descriptors) is determined. But games can’t be given a license until PEGI administrators examine the footage and answers, and get their hands on the game itself in order to review the rating, which may end up being changed.

A hands-on test is a necessity since, as Rice puts it, in their video evidence, developers sometimes “play their games really well, we'd rather they didn't”.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

“We want to know what happens when your character dies, when you accidentally fall in a pit of spikes, when you shoot the hostage that you're not supposed to, all of those things,” he elaborates. “So when it comes to the game examination, that's what we're doing.”

Mind you, examiners don’t generally get to play games from start to finish. Rice tells me that those assessing games get full access to them for around one day, anywhere between three months and a week before their release, depending on how “nice” the publishers are. However, with games usually being given out so many months before their official launch, examiners are normally given a test build, which comes with debug notes and cheats (which, for example, might help them jump around wherever they want) in order to make the process “a bit easier”.

However, such advanced access can be a problem sometimes, Rice reveals. Since so much can change during a game’s development, sometimes content that examiners may have “hinged a rating on” gets removed, which can be “very frustrating”. On the other hand, the onus is on the developers to disclose everything, so if anything slips through the net that wasn’t declared, and subsequently wasn’t discovered by examiners, this is the fault of the developers, not the Games Rating Authority (although Rice reiterates that it’s extremely rare that this happens).

“Unfortunately, for developers, because they didn't disclose it, they are then liable to sanctions,” he explains. For instance, if something had been hidden from a game that was rated a 12, but should have instead been a 16, the Game Rating Authority has the power to remove UK licenses, so that affected games are removed from shops. “So, there’s incentive not to do it,” he adds.

Higher or lower?

As you’d imagine, publishers and developers often aim for specific ratings for their games. “Sometimes publishers get very upset because they didn’t get an 18. [...] Sometimes it can be, ‘We were really marketing our game towards adults’, and like, FIFA’s got a PEGI 3 on it. It’s not a game for very, very young children,” Rice reveals, reiterating that a rating doesn’t determine a game’s target audience, but simply judges its content.

“It can happen both ways as well, they can want a lower rating,” he continues. “If it's for a franchise, they would have got the franchise on the basis that you keep the rating down. Someone like Disney would get very upset if we said, ‘No, sorry, this is a 16.’ So we work with them as much as we can.”

Of course, if a publisher or developer is unhappy with an age rating for whatever reason, they’re able to appeal. Pondering the frustrated developers who’ve gotten frustrated at missing out on an 18 rating, I ask if anyone has ever appealed for a higher age rating. “Sadly not,” Rice replies.

We want to know what happens when your character dies, when you accidentally fall in a pit of spikes, when you shoot the hostage that you're not supposed to, all of those things”

Over the years, some changes have been made to the criteria used to classify different PEGI age ratings, with one recent change leading to Star Wars Jedi: Survivor being given a PEGI 12, despite its predecessor, Fallen Order, having a PEGI 16.

“Last year, any realistic-looking violence towards a human was a 16, which meant things like Star Wars and Spider-Man that have movie equivalents of a lower age rating had a big disparity,” Rice explains. “We do public research on a regular basis, so we did some into violence. We asked our parent panel as well, who were like, ‘You need to do something about this to address it.’

“So we put forward a criteria change, which basically relates to games, typically in a fantasy setting, but where if it's realistic [violence] to humans, but there's no blood, there's no obvious pain or suffering, injury details, no bones breaking or anything like that, that's now fine at 12. So the latest Star Wars game got a PEGI 12 rather than a 16.”

Banned games and illegal actions

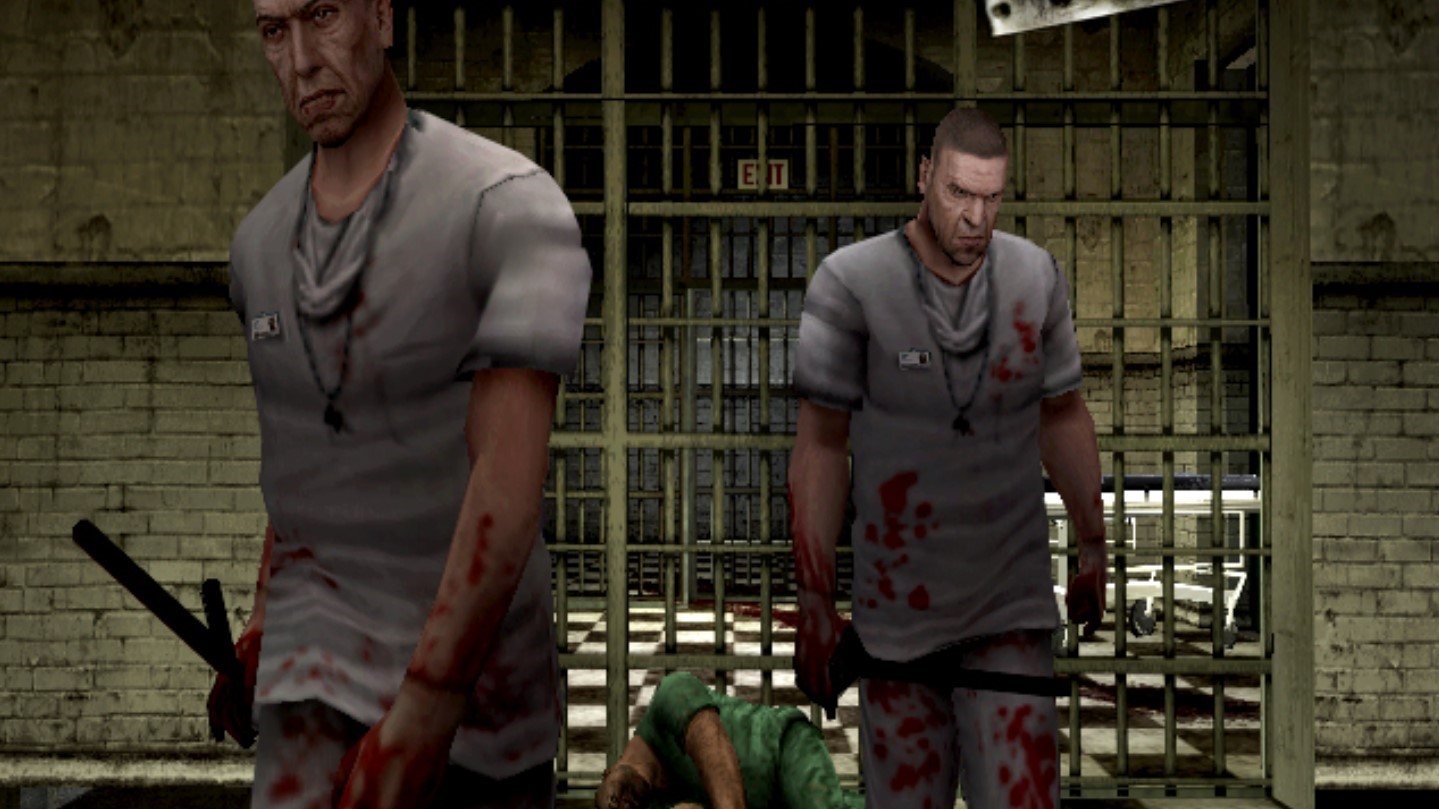

Beyond helping consumers decide what games are appropriate for children or themselves, the Games Rating Authority has another responsibility: banning games that it deems to be completely inappropriate. Since 2012, the authority has only banned one game in the United Kingdom - the dungeon-crawling PlayStation 4 RPG, Omega Labyrinth Z.

Rice tells me that he’d been in his job for around six months when the authority was faced with rating the game. Most of it, he says, was “totally innocuous”, save for a hot spring mini-game that featured a character who appeared to be very young.

“Part of the game is you had to arouse the character on screen using the touch control, and there was one scene with a girl that looked very, very young holding a teddy bear,” he explains. “And you had to sexually arouse the girl. [...] Ultimately, we refused a certificate on the basis that it normalized sexual activity towards children. So that was our reason for it.”

At this point, Omega Labyrinth Z's developer had the option to cut the content or go to appeal, but the decision was simply accepted, and the RPG was never released in this country. Since it never received a certificate to be sold, this means that it would be illegal to sell even an imported copy within the UK, since it would “effectively be an unlabelled product”.

“The customer service guy that handed it over would be liable for a £5,000 fine [and] six months in prison,” Rice says, explaining what would happen if a second-hand copy was ever sold by a UK retailer. “It's the same as if they sold a game to someone underage.”

Admittedly, it’s very rare that someone has faced legal repercussions for selling a game to someone who’s underage. Retailers are provided training by the Games Rating Authority which clearly works quite well - I tell Rice about an instance when I was asked for ID when trying to buy The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess at 16, and was turned away since I didn’t have any. He laughs.

In September 2023, the PEGI age rating system turned 20 years old, and it’s amazing that in two decades, much of what the Games Rating Authority does has been left forgotten, and remains unseen by the gaming community. Walking away from our chat, I was struck with how much goes into rating games behind the scenes, and how genuinely fascinating the whole process is. It may not be a section of the games industry that gets discussed often, but it’s a critical part of the journey that games go on to appear on our consoles or PCs. I personally have a newfound appreciation of it, and I’ll be interested to see how the rating process continues to evolve.

For some great new game recommendations, be sure to check out our lists of the best PS5 games, best Xbox Series X games, and best Nintendo Switch games.

Catherine is a News Writer for TechRadar Gaming. Armed with a journalism degree from The University of Sheffield, she was sucked into the games media industry after spending far too much time on her university newspaper writing about Pokémon and cool indie games, and realising that was a very cool job, actually. She previously spent 19 months working at GAMINGbible as a full-time journalist. She loves all things Nintendo, and will never stop talking about Xenoblade Chronicles.