3D printing in the home: sorry Gartner, imagination is the final frontier

Maybe consumers just need a use before adopting 3D printing

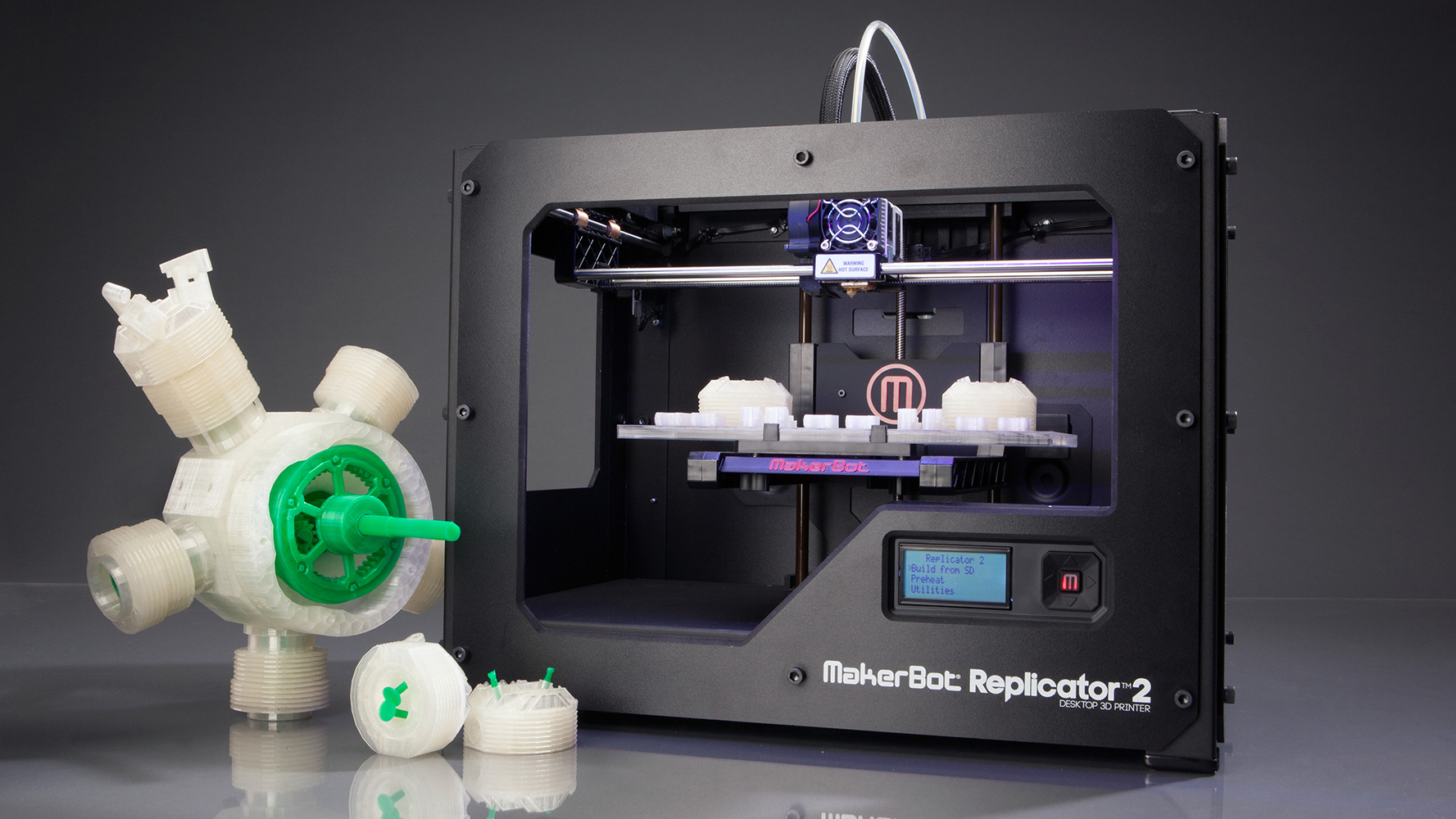

Is 3D printing finally starting to be adopted by the masses? We’re certainly on the cusp if the opening of the MakersCafe, ‘the UK’s first 3D printing café’, in the Old Shoreditch Station, is anything to go by.

Visitors to the café can go and watch a machine churning out models while sitting beneath 3D printed lampshades and sipping on an espresso. The idea seems to be to showcase the magic of 3D printing and provide a space for creative types to get together to come up with ideas and then prototype them on the spot.

Retail-wise 3D printing has already infiltrated Britain’s most famous department store. Selfridges hosted an iMakr pop-up shop last Christmas. Visitors to the shop were able to order a toy from myminifactory.com or scan and print a miniature model of themselves.

Meanwhile, in the world of healthcare, 3D printing is really breaking new ground. Last week the NHS announced that 12 of its hospitals now have the capabilities to 3D print detailed scans of patients’ insides – thereby allowing doctors to rehearse (and speed up) complex surgeries and anticipate problems they might encounter mid-procedure.

Even the International Space Station will soon have its own zero-G capable 3D printer (something the Apollo 13 astronauts could probably have done with when creating their life-saving ‘mailbox’).

So that’s the ‘corporate’ adoption of 3D printers and 3D printing – but when are we all going to have 3D printers in our homes?

According to a recent report compiled by professional industry analysts at Gartner, “The technology remains around five to ten years away from mainstream adoption” because prices are still too high for consumers, and “the software, hardware and materials required for 3D printing” are relatively complex.

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

Prices for capable machines are high, but they’re dropping fast (very fast) and certainly faster than the prices of desktop paper printers dropped prior to their adoption by a critical mass of consumers.

When it comes to software and hardware though, I think Gartner has got it wrong. The software we’ve created for users of our printer is super simple – grab a (licenced) model from one of the burgeoning online databases, add it to a virtual representation of your ‘print bed’ on-screen, and hit print. If you want to, you can resize it / flip it / duplicate it, but these really are basic operations.

But perhaps Gartner was referring to the software used to create the models themselves? If so, I’d point its analysts to the efforts of companies like Sketchup and Tinkercad. Tinkercad is particularly easy to get to grips with, but both companies are far less than fice years away from releasing a true CAD programme ‘for dummies’. Incidentally, other companies have approached the difficulties of modelling from a completely different angle – specifically by trying to popularise and disseminate hand-held scanners that map an object from the outside for a 3D printer to recreate.

Again, I’m speaking from personal experience here, but the 3D printer we've developed is no more difficult to use than my laser desktop (paper) printer. You feed in the end of the plastic reel, the machine grabs it and draws it inside the machine, you clip in the reel and you’re good to go. It takes no longer to change a reel than it does to change the cartridge in a paper printer.

Power users may want to change the print head or print bed, mess around with the temperatures of the machine or material, but everyone else can just get on and print. Needless to say, our machine is far from the only 3D printer out there which has been built with ordinary folks in mind (although we think it’s the most geared towards home users), so it’s hard to justify that Gartner comment about the complexity of the hardware and materials used in 3D printing.

In my opinion, one of the most imposing barriers to the widespread take-up of 3D printers is the fact that consumers aren’t sure what they would use the technology for. When we exhibit the Robox at gadget / technology shows the question we’re asked most frequently is, ‘what would I print with it?’ Too many 3D printing stakeholders still think the answer to this question is obvious – they only give their own answer when prompted - but they should be leading their pitch with it. For example, we envisage families using 3D printers to produce things like handles for appliances, utensils, homewares and, of course, toys. As with all emerging technologies, the uses tend to come after mass production, and it is hard to predict how new tech will be used.

As an industry we need to start emphasizing the uses of our 3D printers first, and the technological miracles we’re working second – or we do if we want a critical mass of consumers to get with the programme, anyway.

When it comes to 3D printing, the possibilities are as boundless as the imagination of whoever’s doing the printing. Kids are hugely imaginative. When I go into schools to give 3D printing classes I am met by children whose minds are brimming over with ideas for things they want to print. But adults are another matter; our imaginations often need a jump-start. As an industry we must provide that jump – or fail.

- Chris Elsworthy is the CEO of CEL, and the creator of the Robox 3D printer.