Turning the sundial back to the era of retro edutainment

Games that teach were once a vital part of the PC gaming space.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Picture this. You’re in the pre-Wikipedia days, back when encyclopedias served as search engines, back when you did the searching. Bored with said encyclopedias, your kids are clamoring to boot up their worn-out desktops made of spare parts. A Halo shootout or an Age of Empires skirmish, perhaps? My Indian parents had a more “educational” idea. As much as I’d like to debunk stereotypes, they brought home several disc-based encyclopedias and lost no sleep over the matter.

A Jurassic-era Pentium 4 CPU, 256 MB of RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce 7300 card kept the living room warm as my CD whirred to life. The static noise from the speakers put the radios to shame. Taking apart the keyboard’s keys and the mouse’s trackball was fun but now was not the time. Not when the installation was done and the title made its way across the dim screen. No day-one patches, no bug fixes, and no internet required.

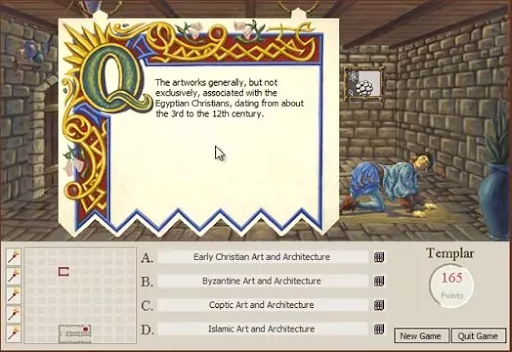

Encarta ‘95 was my internet

I went in expecting enough walls of text to send my mouse scrolling across the country. But Microsoft knew that antsy children wanted more from Encarta ‘95. Videos, interactive media, and links between articles turned a journey into an adventure. But what really sold it for me was the game hidden within its pages: MindMaze. This trivia minigame had me walking through a maze in a medieval castle, answering questions from jesters, kings, and parrots posing as subject experts. The game’s ghost rattled me, not because she still had chains on her arms like a torture victim. It was because I’d have to start over if I didn’t answer her question.

“We were making something that millions of schoolchildren around the world would be using,” says Mark Mackenzie, former designer and program manager at Encarta’s team in a touching video looking back at their work. As an adult, I can’t imagine how its editorial team painstakingly assembled volumes of accurate and crystal-clear content that couldn’t be updated like the sites of today. Encarta would go on to embed links to authoritative sites in its battle against Wikipedia, one it lost in 2009. But when it comes to the entertainment aspect of “edutainment,” Encarta ‘95 and its MindMaze component taught me a great deal without me knowing it.

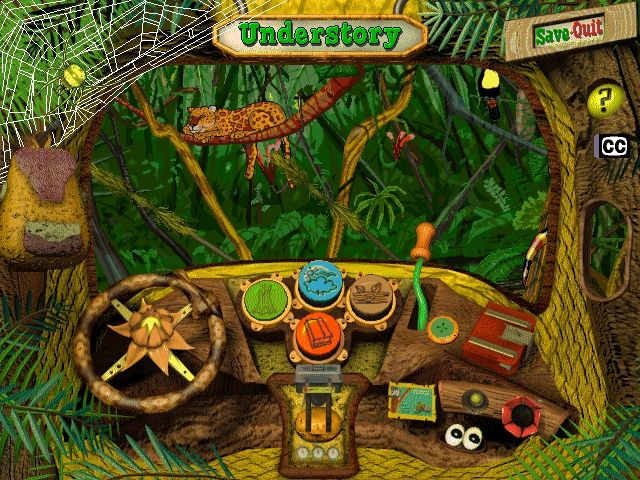

The Magic School Bus: literally a vehicle for education

Encarta wasn’t Microsoft’s only attempt at the edutainment throne. It also published educational videogames set in the world of Joanna Cole’s acclaimed The Magic School Bus franchise. Her books blurred the line between fact and fiction with a school bus that could switch from submarine to time machine with the wacky Ms. Frizzle at the helm.

The books also featured a diverse cast of characters with unique takes on whatever bizarre situation they found themselves in. Representation meant a lot to kids who felt like they didn’t belong. Microsoft’s edutainment games leaned towards the entertainment side this time around, with minigames and puzzles that reeled young players in before teaching them.

While I didn’t learn a lot from assembling dinosaur bones or looking for camouflaged animals in the rainforest, The Magic School Bus games sprinkled tidbits of information between these minigames. The Age of Dinosaurs taught me about the Earth’s distinct time periods and the wildlife that inhabited them. Hanging out in the rainforest canopy or chilling by the river let me interact with plenty of flora and fauna right where they belonged. It’s an experience I remember fondly to this day, surpassed only by my love for yet another edutainment surprise.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

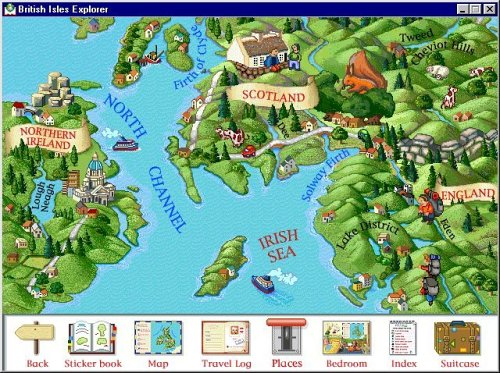

My First Amazing History Explorer was my time traveler passport

Before in-game collectibles went mainstream, publisher DK made an educational game out of that single concept. DK’s My First Amazing World Explorer fills my mouth quicker than cornflakes so let’s stick to “World Explorer.” The game featured an expansive world map that gave young players a taste of the world’s diverse geography and its people. A sticker book had you scouring the globe in a treasure hunt and completing it became a win condition I set for myself.

Sounds, visuals, and even animated features covering cultures and technical advancements alike set the stage for an immersive learning experience. Moving across continents using various modes of transport helped uncover even more surprises and sticker-collecting opportunities. World Explorer led me to History Explorer, a time-traveling sequel that sends you on a trail across eight major historical periods. The sequel featured a story behind the sticker collection this time, with more fleshed-out animations and an adventure through the rise of Egypt’s pyramids to the Industrial Revolution.

History Explorer taught me about world-shaping events across history, sparking in me the desire to learn not just what happened, but why. Both Encarta and The Magic School Bus helped me become an inquisitive student. This desire has stayed with me all these years, teaching me to respect nuanced worldbuilding systems employed by games and novels as well as appreciate the inner workings of machines as an engineer.

Edutainment is a gift I am grateful for

I found the idea annoying as a child, I’ll admit. But I grew to understand that educational games conveyed information in ways words never could. They opened my eyes to a world filled not just with fascinating discoveries and cultures but also one steeped in conflict and desires that shaped nations. While edutainment does keep its gloves on and grins as it explains wars and weaponry, it didn’t take long for me to understand that only the winners get to write history as they see fit.

Edutainment taught me that awe and wonder didn’t just belong to a screen. It belonged out there too, in examining the delicate web of inter-connected strands that make up our planet, be it those of living beings or the wonders we’ve discovered or built over the ages. With Wikipedia and dozens of search engines at our fingertips, it’s easy to take this information gateway for granted. I am glad that I entered the world when the internet was in its infancy, a time when the answers to any question weren’t a Google search away.

Antony is a freelance contributor at TRG. His writing warps from shooters and strategy games to fiction (to-do lists). Antony's words have found a home across sites like IGN, Rock Paper Shotgun, and Kotaku AU. You'll spot him thriving at both chaotic LAN parties and silent libraries. Or on Twitter.