They're people, not end-users: why the tech industry must ban buzzword bingo

Banish the de-humanising terms

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Power to the end-users! Forget natural language processing algorithms – most of the tech industry has no clue about natural language. In my long career as a tech journalist I've received so many press releases and sat through hundreds of PowerPoint presentations about so-called life-changing gadgets where the supposed audience were openly called consumers or end-users.

That won't surprise anyone – both archaic terms are hard-wired into tech-speak – but it's got to stop. Such obnoxious language is fast infecting politicians, too, who so often now say 'consumers' when they mean the equally derogatory 'voters'.

What they – and all businesses – mean is 'people'. Using that simple term makes a company instantly appear more human. With the rise of people termed millennials (typically defined as people born from 1983 onwards), it's a step-change that could soon be necessary to save a tech business from obscurity.

The time-bomb under tech

The tech industry's language is incredibly naïve. Interwoven with dated business-speak, products that promise 'an exceptional end-user experience' or reports into 'increasing end-user trust' just sound so awful. It can't last. Millennials will make up 75% of the workforce in 2025, and a new survey of 24-35 year-olds reveals how the global language of business will need to change with their rise. Building a modern tech business means using modern, inclusive language.

Millennials get tough on tech

That the tech world borders on being anti-human isn't going unnoticed. It's a fear we've expressed before, but a report by Intel discovered that the majority of young people believe that tech makes their lives easier, but makes them less human.

The survey of 12,000 18 to 24 year-olds – the so-called millennials – in Brazil, China, France, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan and the USA found that 59% say people are over-reliant on technology, believe it makes people less human, and they desire technology that is more personal and knows their habits.

"At first glance it seems millennials are rejecting technology, but I suspect the reality is more complicated and interesting," said Dr. Genevieve Bell, anthropologist and director of Interaction and Experience Research at Intel Labs. "A different way to read this might be that millennials want technology to do more for them, and we have work to do to make it much more personal and less burdensome."

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

Negative language

For technology to be more personal, the tech industry needs to communicate better internally as well as to people who are its potential customers. Just as people investing in new IT products don't want to be called 'end-users' or even 'consumers', nor do they want to be described as 'staff' or 'stakeholders'. Done properly, technology is about innovation, opportunity, purpose, wonder and collaboration, and about being creative within a community, a team or a family. It's about people.

Touchy-feely language gone wrong

The box around a product is vitally important, and it's here where language is crucial. "Packaging plays an enormous role in supporting a brand's story, particularly in the tech industry where appearances are everything," says Ben Davies at Rodd Design. "It's very often the first touch-point you may have with the product, if bought online."

A lot of the big brands understand what it is to speak on a human level, and simply say 'Welcome to WeMo' or, more famously, 'Welcome to iPad' on their packaging. The sub-text is as simple as the language; you're in the club.

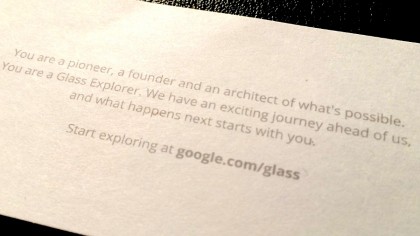

Some go super-human, with hilarious consequences. Open up the Google Glass box and there's a note that reads: 'You are a pioneer, a founder and an architect of what's possible … what happens next starts with you.' Actually, what happens next in our experience is a few days trying to work out how to operate Glass and get it online, mustering the courage to go out in public, and ultimately figuring out how to return it (though Google has, of course, just announced that it is ending the Glass Explorer Program next week anyway).

Despite Google overdoing it with Glass, its messaging is a valiant attempt – the use of straightforward English language is usually very effective, and tech-speak is not. However, the birth and death of buzzwords isn't the big problem here. Terms like 'crowdsourcing', 'next-gen' and 'web 2.0' have been buzzing around the tech world for years despite meaning very little, but they're innocent enough.

Or are they? 'The Cloud' has been top of the list of tech buzzwords for the last five years, but no-one really wants to talk about why. People love the cloud. It's convenient when using mobile devices, or even when not, and it's often free to use. Its popularity is why it's growing so fast, surely? As the tech industry knows, that's not actually the case; the cloud is the perfect place for companies to access 'end-user data'. And that's about as dehumanising a term as it's possible to utter.

Jamie is a freelance tech, travel and space journalist based in the UK. He’s been writing regularly for Techradar since it was launched in 2008 and also writes regularly for Forbes, The Telegraph, the South China Morning Post, Sky & Telescope and the Sky At Night magazine as well as other Future titles T3, Digital Camera World, All About Space and Space.com. He also edits two of his own websites, TravGear.com and WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com that reflect his obsession with travel gear and solar eclipse travel. He is the author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners (Springer, 2015),