How Roadwarden converted tabletop ideas into a game of choice

Telling a story with more words than actions

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

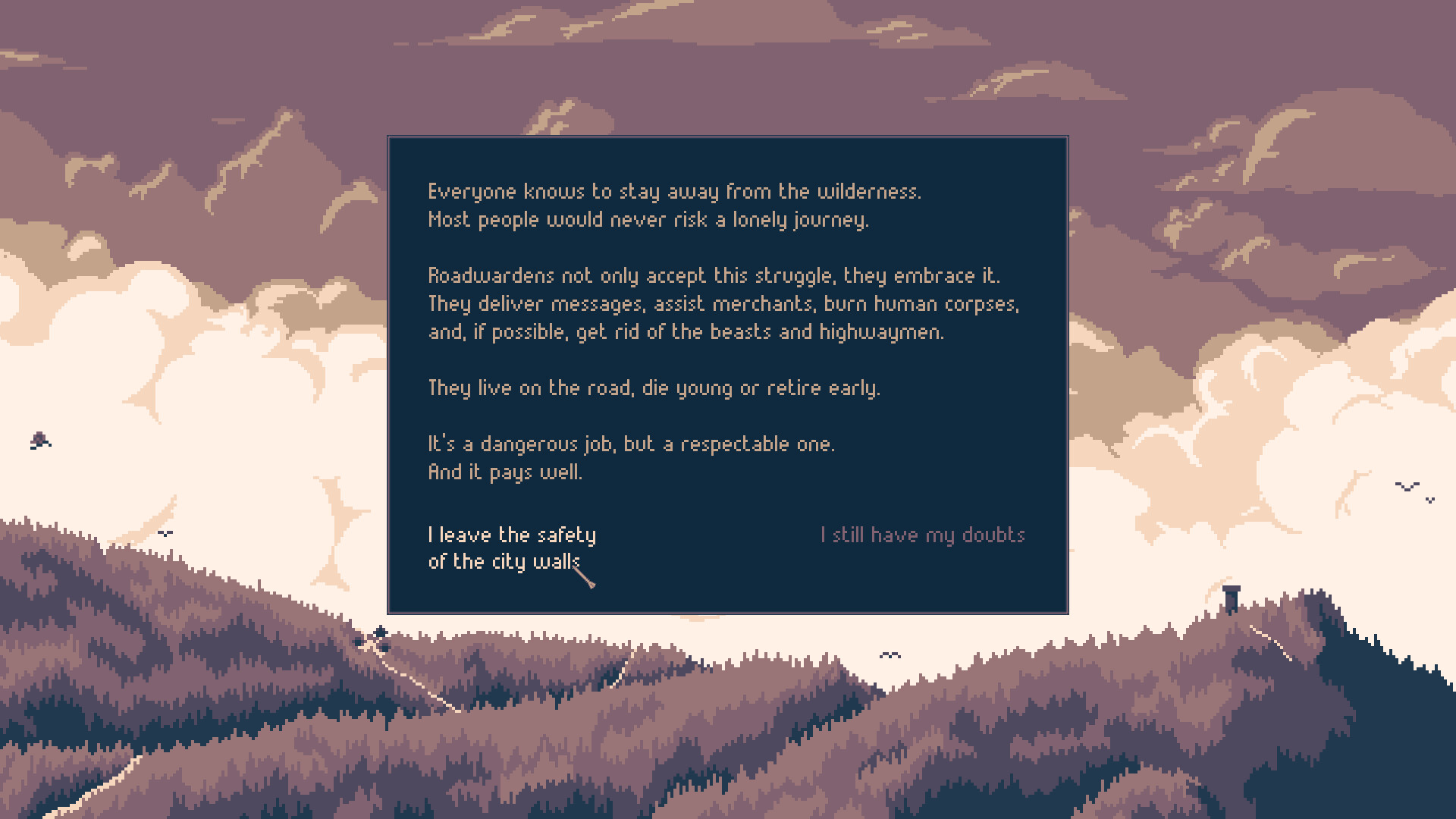

Roadwarden begins with a choice. If you decide to start the game, a message pops up, explaining the danger of being a Roadwarden (a sort of helpful traveler who will normally ‘die young or retire early’), and asks if you really do want to leave the safety of your city. The refusal option varies — excuse after excuse, if you keep clicking it, about checking your supplies or your horse, spending more time with your loved ones, or going to the alehouse. Eventually, the excuses run out, and the option is no longer available. You can either venture forth, as Baldur’s Gate would put it, or exit the game. It’s an appropriately ominous introduction to its world.

Roadwarden is still a very new PC game – it was released in September, and is also available on Mac – and it has been received well by both critics and fans. The developer, Aureus of Moral Anxiety Studio, has described the game as hostile, grim, and perfect for Autumn. It’s an apt description, from what I have played, and I asked him about the reasoning for these dark qualities.

“In part,” he says, "my personality is to blame. I’ve got no comedic talent, no strong attachment to a belief system that I would like to sell to others, no vision that keeps me hopeful about the future. In Ancient Greece, I’d be called a melancholic, but developing the game during the pandemic and the unjustified Russian invasion happening just outside my country’s borders definitely didn’t help.”

The objectives of this story

His goal was “a humble tale, focused on tiny tragedies and personal tales. It’s not a game about a chosen one or a legendary hero, but rather about a lone traveler who tries to do their best in the world, against all odds, to fulfill their own goals in a world that, in some ways, has already collapsed.”

(It’s no surprise that one of his inspirations, Baldur’s Gate, fascinated him with the use of an iron shortage as part of its plot.)

Another classic influence, which incidentally celebrates its 25th anniversary this month, is Fallout. The scene that particularly sticks out for Aureus is the interaction you have with the final villain of the game:

“There’s an option to “defeat” them without violence, by bringing up an obscure detail of lore that the protagonist can stumble upon during their investigation. This is one of the main tools aiding the player during social conflicts in Roadwarden.”

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

“But,” he continues, on the general note of the way classic old games have influenced him, “I was more interested in pursuing what I perceive as the soul of these games. They’re fantastic environments to sink in, despite all their threats and dark forces. I entered them repeatedly as a teen, never seeing them as hindered by their text-based dialogues or lack of fancy cutscenes. The style of writing used in modern high-budget RPGs, filled with witty remarks, friendly banter, and fully voice-acted, is just not what I’m looking for.

Narrative first

Thankfully, there are other modern games that are willing to go in-depth with their characters and stories, such as Disco Elysium or Tyranny, but in some ways I’m still pursuing the highs I experienced as a young nerd, having video games not just for fun, but also for introspection. Planescape: Torment is the most important game of my life, even though it’s not the most obvious of my inspirations, considering how colorful, playful, and insane its setting is.”

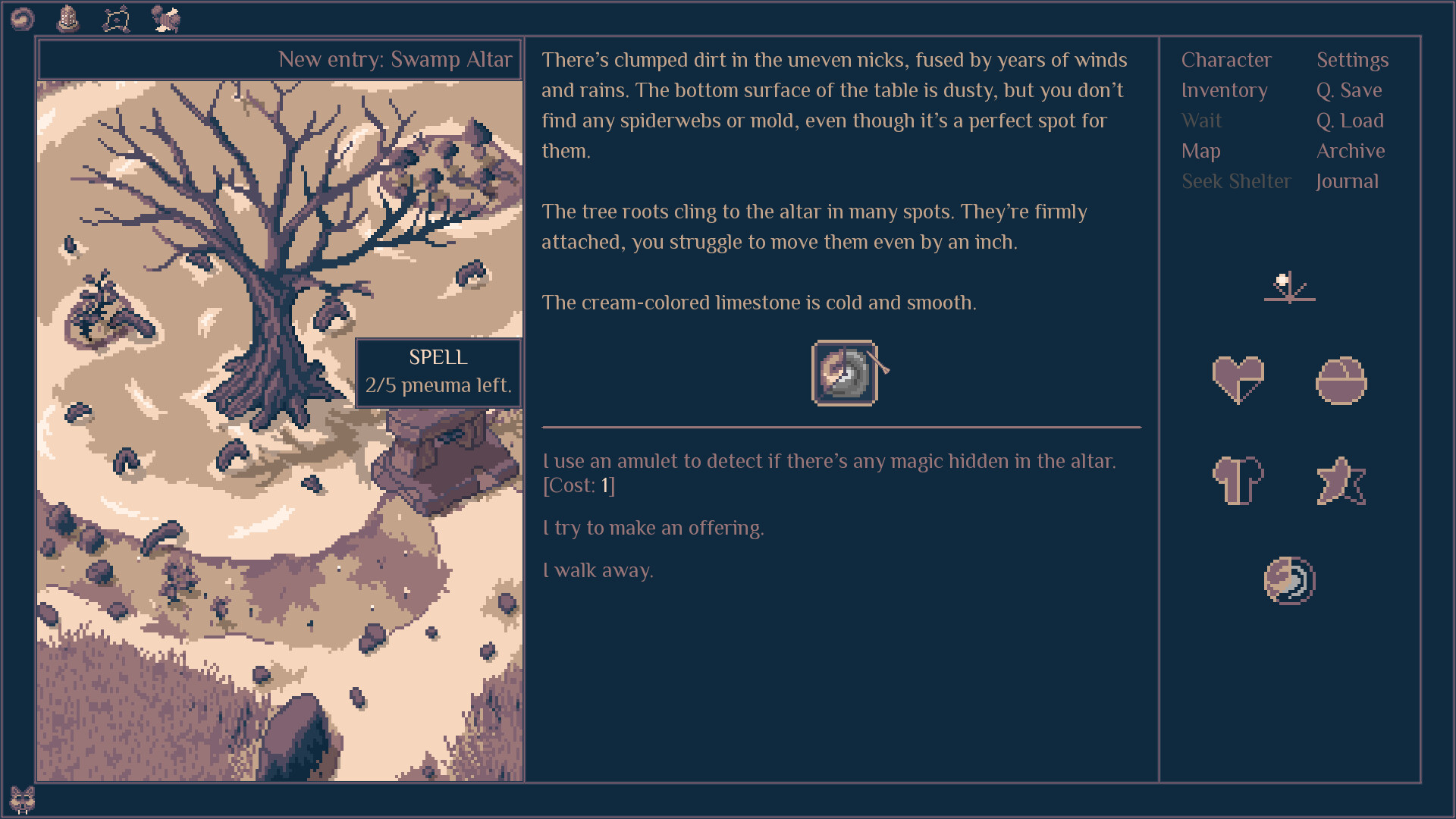

The Steam page for Roadwarden describes it as an ‘illustrated text-based RPG’, and the game has invited various comparisons to fantasy fiction. Aureus is very familiar with literature, having studied and written “free verse and minimalist poetry”, and he mentions two specific novels that influenced his work on the game.

“Two novels that hit me right in the gut as I was developing Roadwarden were George R. Stewart’s “Earth Abides” and Olga Tokarczuk’s “The Books of Jacob”, [the latter] only recently translated to English. Both of these novels left a deep cut in the game’s story and setting, and the latter of them may be one of the greatest works I’ve ever read.”

The universe of Roadwarden

Roadwarden takes place in a fantasy world (influenced by Warhammer, the work of Hayao Miyazaki, and Aureus’s experience with the game Gothic) that Aureus has worked on for over ten years. It’s named ‘Viaticum’, and it was born from his need for a setting for his tabletop RPG system:

“Many people would expect I now have a Tolkienesque shelf of manuals, maps, bestiaries, chronicles, and so on, but the opposite is true - I keep reshaping the small corner of Viaticum I’m most interested in, pursuing specific goals. I play with turning vague ideas into something more materialized, trying to find out what could have happened if they were led to a logical conclusion. My setting remains humble, but to me personally, it’s more interesting to consider how its dwellers perceive sleep, food, animals, or sex than what sort of military strategies kings use in faraway continents.”

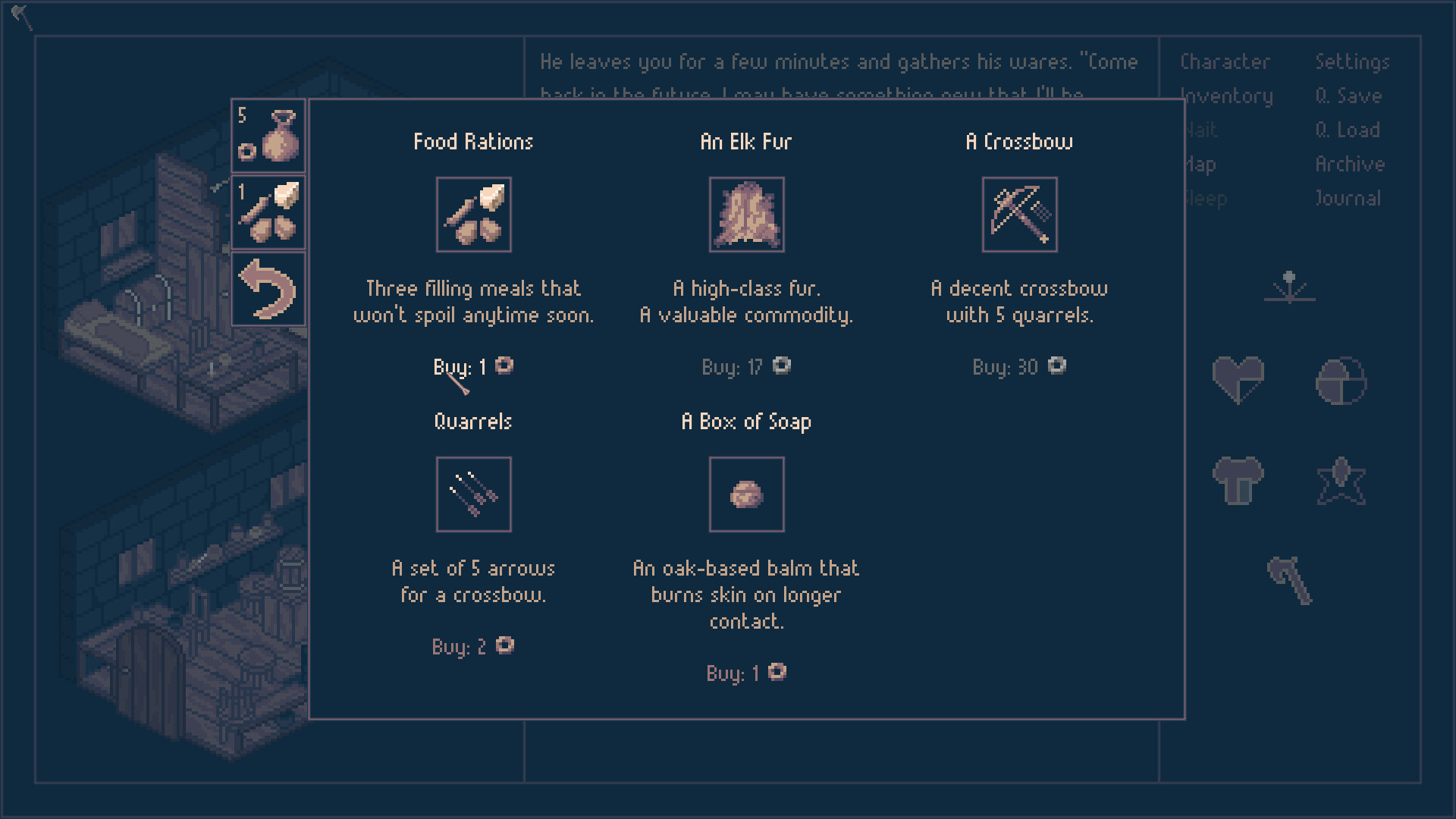

Reactivity, too, was also very important to him. As in a game like Inkle’s 80 Days, there are all sorts of story scenarios. You choose how to approach places, what to say to people, and even how you treat your horse.

“It’s hard to explain how absurdly obscure some bits I wrote are. It was crucial for me to give each player the illusion that the game fully recognizes their journey, as if everything that happens to them is organic and intended, even though I have no idea which quests they’ll pursue, which roads they’ll explore first, which NPCs they’ll like the most.”

Making a game isn't easy

This target of reactivity proved to be costly in terms of the game’s code and the potential for ports, apparently: Aureus blames himself, noting that he is “not a real programmer, just a monkey with a keyboard and a helpful game engine, and right now the game’s spaghetti code is such a mess it may never be ported to another platform, or translated to another language.”

With that said, he does seem to derive some satisfaction from how Roadwarden has done justice to his world of Viaticum.

“I wanted Viaticum to portray a fantasy realm in which nature overwhelms humankind. Therefore, the wilderness was meant to be the main obstacle put in the way of players.

This concept has stuck with me ever since, but the way I introduced it to the world was lacking, and my first video game projects didn’t correct it. Roadwarden is the first project where I see this world fully working outside of my tabletop campaigns, and it may be that only now I’m ready to close this chapter of my life.”

Roadwarden is available on Steam, where it currently holds an 'Overwhelmingly Positive' rating.