Bletchley Park’s codebreakers still have lessons to teach

Humans are always the weak link in the cyber-security chain

James Gray is the managing director of cyber and intelligence, Raytheon UK

The breaking of the Enigma code is rightly considered one of the triumphs of the Allied war effort.

This landmark feat marked a significant turning point in the conflict, saving thousands of lives, and bringing the Second World War to earlier end, in no small part thanks to the genius of Alan Turing and his team, who ensured that German Air Force signals could be read at Bletchley Park from the middle of 1941.

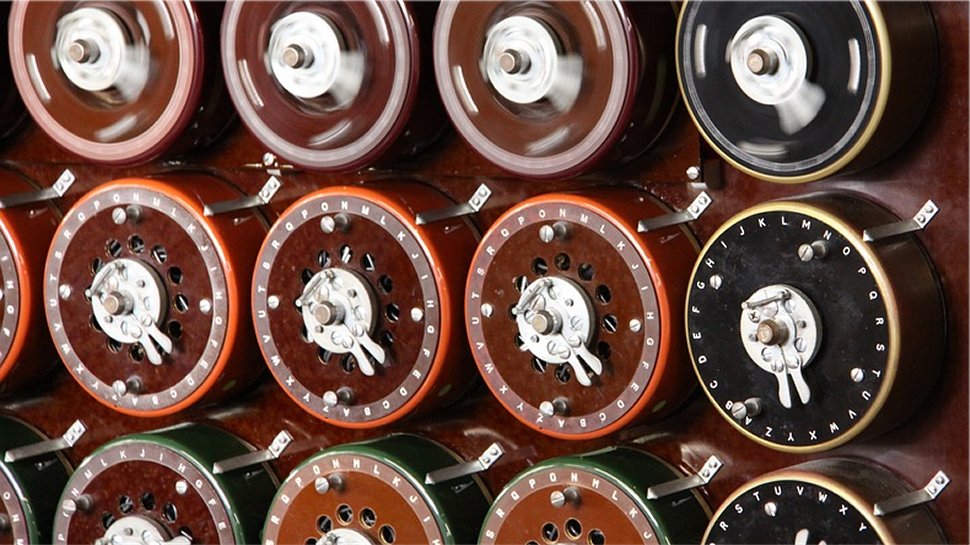

Shattering the system was a triumph of mathematics by some of the finest minds operating in Poland and the UK, supported by Allied captures of hardware and – crucially – German operator errors. But the Enigma code, of course, wasn’t the only system used by Nazi Germany.

Attending the Science Museum’s brand-new exhibit on the history of British code-breaking as it launched last week, I was surprised to learn that an entirely different - and much more sophisticated - system was also vital, not only in turning the tide of the Second World War, but also in advancing British computing history.

What’s more, the story of breaking this code also feels strangely instructive for the modern world of cyber-security.

The Lorenz Cipher

At the height of the Second World War, the Lorenz Cipher was considered uncrackable, and was relied upon by German forces for the vital task of communicating hugely significant messages with High Command in Berlin.

And yet it was decoded, not only by sheer human intellect – though that was clearly a huge part – but also because it required a lengthy and difficult process that had to be undertaken by a person, rather than an automaton.

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

In August 1941, a German operator had to send a message of some 4,000 characters from one part of German high command to another. He set up his Lorenz machine, duly typed in the lengthy missive and considered the onerous task complete. However, he soon received a response in German over the radio: “Didn’t get that – please send again”.

Well, this had been a substantial and draining exercise already. And facing the task of beginning again from scratch, the operator decided he could actually achieve the same results much more quickly with some small changes. He reset his Lorenz machine to the same position - itself a forbidden act - and began abbreviating his text. “Spruchnummer” – German for message number - could become “Spruchnr” and so on. In doing so, the operator managed to save himself some 500 keystrokes.

But, like many coded transmissions, that message was intercepted and conveyed to Bletchley Park. And it gave the British two messages which shared almost exactly the same content, but slight variations in text. It gave codebreaker John Tillman just enough to work with.

Over the course of months, Tillman and his team were able to reverse engineer the entire Lorenz system. The intelligence value of these intercepts was immense, and as academics, business and government all came together, to support and invest in new technology, they led to the development of “Colossus”, the world’s first semi-programmable electronic computer.

And it all began because an exhausted German operator couldn’t face the prospect of transmitting another 4,000 character message back to base.

From Ciphers to Cyber Security

This is just one of the fascinating stories laid bare by Top Secret: From Ciphers to Cyber Security as it details a century of British communications intelligence, all the way to modern day GCHQ. Raytheon is proud to support this exhibit as part of our commitment to inspiring a new generation to think about careers in the UK’s cyber and digital sectors.

But, as I visited the exhibit on its opening day, it was the story of the Lorenz Cipher that leaped out to me, as particularly significant.

Perhaps because it’s such a clear distillation of a powerful rule that we sometimes fail to remember in the modern world of digital security today.

Just as a convoy only travels as fast as its slowest ship, a chain is only a strong as its weakest link. And in security terms, we are undoubtedly the weakest link.

Of course when it comes to cyber, there is a natural temptation to talk about the technology, the big innovations and the malware, the breaches and the losses. But if we want our businesses and our critical national infrastructure to be secure in a new world of cyber conflicts, the real focus must be the people.

The persistence of human error

Training and education may not seem exciting investments, but while humans operate the machines, they represent the best prospect of protecting your data and that of your customers and your citizens.

Because just as the Bletchley Park codebreakers showed, it’s not just about the black box. It’s also about the person who uses it.

And when everyone understands that, we’ll have a much safer digital world.

James Gray is the managing director of cyber and intelligence, Raytheon UK.

- Check out the best free anti-malware software