These developers are putting game preservation front and center

Giving classic games a new lease of life

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A staggering 87% of classic games released in the US are at risk of being lost to time, particularly with the low availability of these games across platforms, according to a study by the Video Game History Foundation. Even as the massive cultural impact of video games dwarfs the music and film industry - with the games industry valued at over $300 billion - it still feels like video games are shambling towards demise.

When it comes to preservation, some companies aren’t ready to ensure long-term access to their old library of games. In 2022, Epic shut down online services for 17 older games, which renders all of the classic Unreal games - including Unreal Tournament 3, Unreal Gold, and Unreal 2: The Awakening - effectively unplayable; that is, unless you already own the game. Then there’s Nintendo’s vehemently anti-preservation decisions, with the entertainment behemoth ceasing sales of 1,000 digital-only games from its Wii U and 3DS online store, thus removing legal access to these games. That means that if you wish to play these games today, fans may have to resort to old-fashioned piracy.

Admittedly, game preservation is hard work. Outdated copyright laws, as stated by the Video Game History Foundation, are a significant obstacle, with legal restrictions that limit access to intellectual property, typically owned by videogame behemoths like Nintendo. Changing trends in the industry, such as the gradual shift towards exclusive digital titles and frequent updates, also translate to the need for dedicating a sizable amount of resources to the endeavor.

Luckily, there are still developers out there who aren’t deterred, as they look to tackle the thorny field of game preservation by actively saving legacy games. Some are even developing their own proprietary engines so these games can be played on modern systems.

Keeping the flame alive

One of them is the American developer Digital Eclipse, which specializes in producing emulations of arcade games, such as the Williams Digital Arcade series, for PC and Macintosh. Several mergers and acquisitions later, the studio was revived in 2015 with a focus on preservation. This new goal was informed by the studio’s head of restoration, Frank Cifaldi, and his experience as a preservationist.

“We believe that classic games are not treated with proper respect,” the editorial director at Digital Eclipse, Chris Kohler, explains. “Legacy games are not just old products to be dusted off and shoved back out in the marketplace to make a few bucks. This is the foundational art on which the video game industry and the medium of the video game were founded, and they should be treated very much like classic films.”

Core to Digital Eclipse’s ideals on this matter is the Eclipse Engine, a specialized engine for the studio to create original games. It lets the developers weave in multimedia experiences in the vein of the Gold Master Series - the studio’s name for its interactive documentaries. At the same time, it allows emulators, developed in-house, to work seamlessly with one another. This is so that games that were first released on discontinued consoles can remain playable across most modern platforms.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

It's tragic to put something like that in front of someone and have them not understand why it's so important

Chris Kohler

“If you care deeply about video game history, you should take a look at each of the Gold Master Series games,” says Kohler. “We are going to paint the full picture, tell you the full story of why that game is so important, and give you all of that context.”.

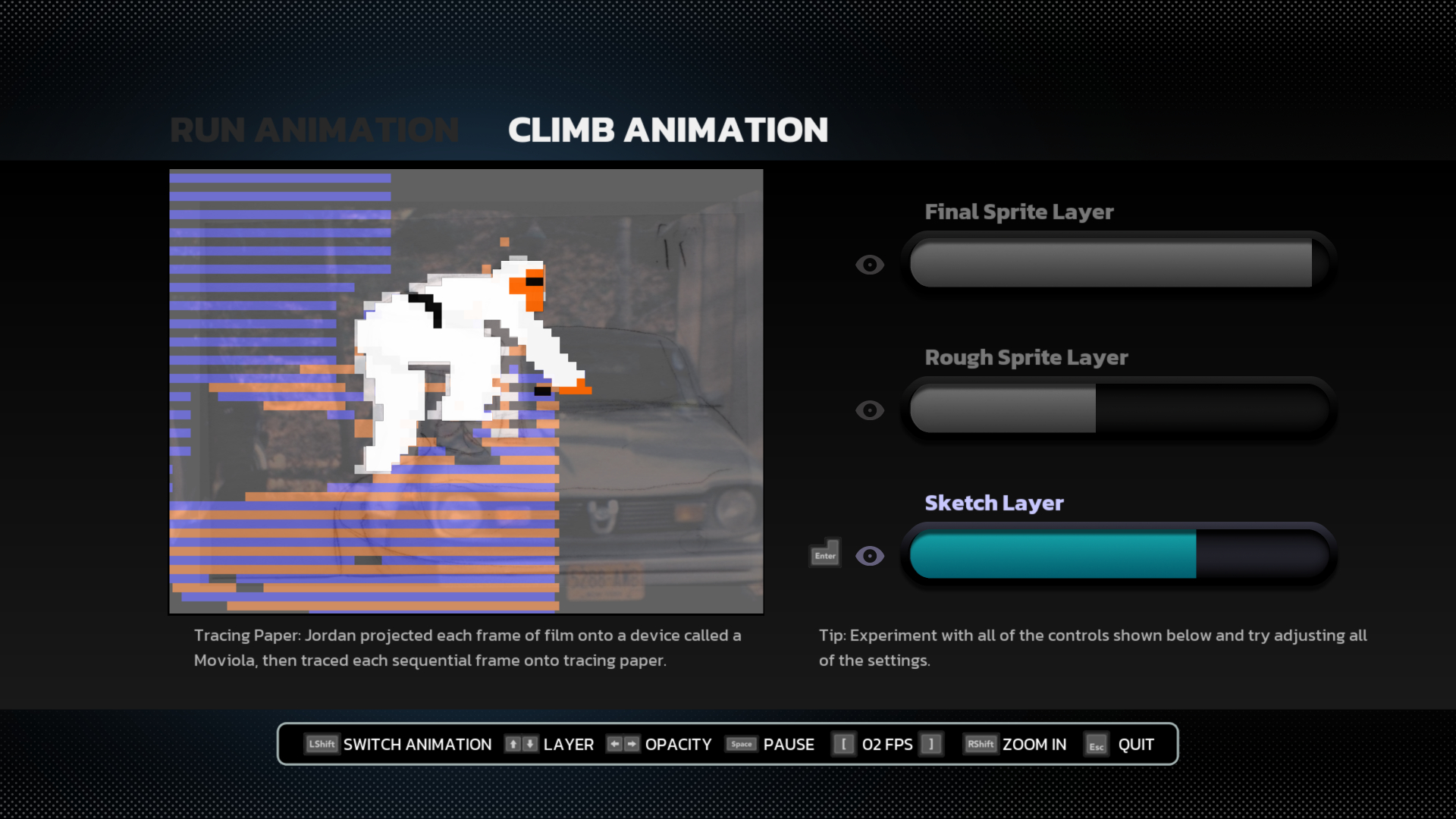

To Digital Eclipse, this preservation approach can also dismantle common misconceptions about video game history. First, there’s the rise and fall of Atari and Nintendo’s sheer dominance of the industry years after. Then there are stories like the development of the 1984 action game Karateka, something that was deeply influential for a generation of game designers.

“Personal computers thrived in 1983, ‘84, ‘85, ‘86… and makers of game software for personal computers were thriving,” Kohler explains. ”One of those people was [Karateka creator] Jordan Mechner. Karateka was made in 1983 and published in 1984, and it was a ground-breaking achievement that really pushed the medium of video games forward in a big way.” Merely bringing the game back to modern consoles isn’t enough; according to Kohler, players may not understand how influential it is by just playing it.

Digital Eclipse also hopes to re-release more classic games as interactive documentaries. “Beyond Karateka, when we're looking at video games to bring back, we're trying to take a story-first approach, and it's like, what is the interesting story that we could use these games to tell,” Kohler admits. “If we can do that, it’s doing the best service for these games that we can. It's tragic to put something like that in front of someone and have them not understand why it's so important.”

Another joins the fight

Then there’s Nightdive Studios. In the same vein, the American developer also has a proprietary engine that drives its preservation efforts, the Kex Engine, but its approach differs slightly from Digital Eclipse’s vision. For a start, the engine is what the studio founder and CEO, Stephen Kick, describes as the “backbone of all our remastering efforts.”

The act of creating physical media for games can complement preservation efforts

“We can more or less wrap the source code in the engine, which enables us to change just about anything we want, adding stuff like widescreen mouselook in the case of System Shock, accessibility options, controller inputs, rendering devices, so that we can port the game to various consoles, that sort of thing,” Kick adds.

Nightdive Studios wants to revive classic games it loves, including abandonware games (games that are no longer published or supported by their creators), and introduce them to a new generation of players. After all, Nightdive Studios was founded when Kick discovered that he couldn’t purchase System Shock 2, which was unavailable back in 2012. The re-release of System Shock 2 eventually became the developer’s first title. “It was just basically a list of games that I had played with my dad that I wanted to have back out there again,” says Kick.

Part of the appeal of Nightdive Studios’ games is the nostalgia they invoke. They play as well as your sepia-toned memories of late-night gaming with your face aglow in the warmth of your computer screen. “Nightdive’s mission is to bring back lost and forgotten titles and make them playable in as many ways as we can,” says Larry Kuperman, director of business development at the studio. “We like to say that you can always tell a Nightdive game, because our games play the way you remember. Not the way it actually played because you were playing it on antiquated hardware. It brings back the same emotions, the same energy, and the same enthusiasm that the original did.” At times, this can mean removing the limitations of playing these games on older hardware, such as the lack of mouselook in the original System Shock. In particular, Nightdive Studios eventually implemented this feature in the game’s enhanced edition.

Another example of this ingenuity is seen in the first-person shooter Turok. ”In the original game, your sight distance was very much limited by the fog, and in speaking with the developers, we learned that the reason that the fog was implemented was because they wanted to have a level of detail that had never been seen before, and the hardware could not support that for very long draw distances,” adds Kuperman. “So when we created Turok, and this was under discussion with some of the people that were involved in the development. We made a choice: you can play Turok… the default is with the fog rolled back. But you can also play it with a fog; you can enable that feature.” According to Kuperman, changes from such updates are often minimal.

Nightdive Studios most recently released its remake of System Shock last year. This isn’t just about ensuring that the game can be played on most platforms today, but also about updating the game with a more modern control scheme. “That whole decision stemmed from our work on the enhanced edition of System Shock, where we had brought on a number of modders that had kept the game alive throughout the years to work on our version,” Kick explains. “When they implemented something as simple as mouselook, it really sparked our creativity. And we thought a lot more people would probably enjoy this game if it had mouselook, if it had modern controls. It would be easily accessible.”

Limited Run Games is another studio that’s set on preserving the industry’s vast legacy - by producing physical versions of classic games. To the studio, the act of creating physical media for games can complement preservation efforts, particularly in a landscape where digital games are just as swiftly released as they are lost in time.

“The big thing about physical games that is important to me is the actual ownership of it,” says Josh Fairhurst, CEO at Limited Run Games. “When you buy a game digitally, you don't actually own the game. You have a license to download the game, to install it, to play it, but that license can be revoked at any time if the platform holders decide that, for whatever reason, they can't continue allowing that game to be downloaded.”

To facilitate this process, Limited Run Games also has its own engine - the Carbon Engine - to help publishers release their old library of games cost-efficiently and with ease. Like Nightdive Studios’ Kex Engine, Carbon Engine also allows various emulators, which include that of legacy consoles, to be used with modern hardware, but it’s one that Limited Run Games believes would be easy to use.

An uphill battle

The challenges of game development are well documented. Part of the significant obstacles faced by these preservation-focused studios is a whole lot of sleuthing: hunting down the studios or individuals who own the copyrights, unraveling the source codes for these games, or simply looking for any remnants of the original game in physical form. These copyrights can be a legal minefield, and may not even extend to parts of the game such as music, soundtrack, and even voice acting. Then there’s the issue that crucial paperwork, from decades ago, was simply not digitized. “Some of the records are contracts that we've never been able to find because they're stored in a box, and maybe somebody's garage or in the basement of the building someplace,” explains Kuperman.

Source codes, too, can also be poorly preserved or lost by the original developers themselves. “Sometimes we don't get access to the original source code for a game, and so in those scenarios, we'll have to reverse engineer the object code, or basically what was shipped on the disc,” explains Kick. “Some of the systems are left up to our interpretation, and so they may not be as accurate as it was originally designed or the way that it was originally developed.”

We're putting this in as a museum exhibit to help you understand the path that a certain company took

Chris Kohler

“You need that source code access to ensure that the game can continue to be ported or brought to new hardware,” Fairhurst elaborates. “If another developer comes along and says, ‘We're willing to put the money into port,’ one of the problems that are often encountered, and I'm sure Nightdive probably brought this up, is that the source code is often lost because the developers and publishers never thought to take care of it.”

But for Digital Eclipse, the most pertinent challenge is in the details. Fixing code that doesn’t quite work for modern platforms, making slight tweaks so the game is much more accessible, and determining whether bugs require squashing or a unique characteristic of games at that time - these are a tightrope to tread so as not to diminish the cultural context of these legacy games, including their quirks and oddities. Even preserving games that can be considered bad or janky by today’s standards is important work for the studio. “The game actually doesn't need to be fun because, if we're setting the player's expectations correctly, we're not asking you to go in and play this and derive simple enjoyment from it; we're putting this in as a museum exhibit to help you understand the path that a certain company took, or game designer might have taken to get to the final goal, or simply to show you something that's historically fascinating,” says Kohler.

Such an approach may seem at odds with Nightdive Studios’ priority of making classic games more playable. Yet, as Kohler points out, the more copies of a game that are made increases “the odds that it will survive.” And in the end, the very act of preservation is also a labor of love. Whatever form this takes - be it Digital Eclipse’s emphasis on also preserving the cultural context of classic games at their time, or Limited Run Games’ focus on producing physical media to ensure the games’ longevity beyond just digital - it will only strengthen preservation efforts in the long run. In an era where our favorite games are rapidly perishing, beholden to the whims of companies that find little material incentive in keeping them available, the games preservation field will need all the help it can get.

If you’re looking for more older games with a modern twist, check out the best video game remakes that are available to play right now.

Khee Hoon is a freelance journalist and editor from Singapore who writes about games, music and culture. Their bylines includes Polygon, Rock Paper Shotgun, PC Gamer and Eurogamer. Ask them about the weather on Twitter: @crapstacular.