The quest to cut Google out of your digital life

Proton is building a privacy-centric alternative to the Google software ecosystem

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On June 6, 2013, The Guardian and Washington Post published reports exposing the indiscriminate surveillance of citizens carried out by the US government and its allies. The source: ex-NSA contractor Edward Snowden.

When Snowden leaked the initial trove of classified documents almost a decade ago, he unmasked an uncomfortable new reality: in the internet age, privacy is no longer a guarantee.

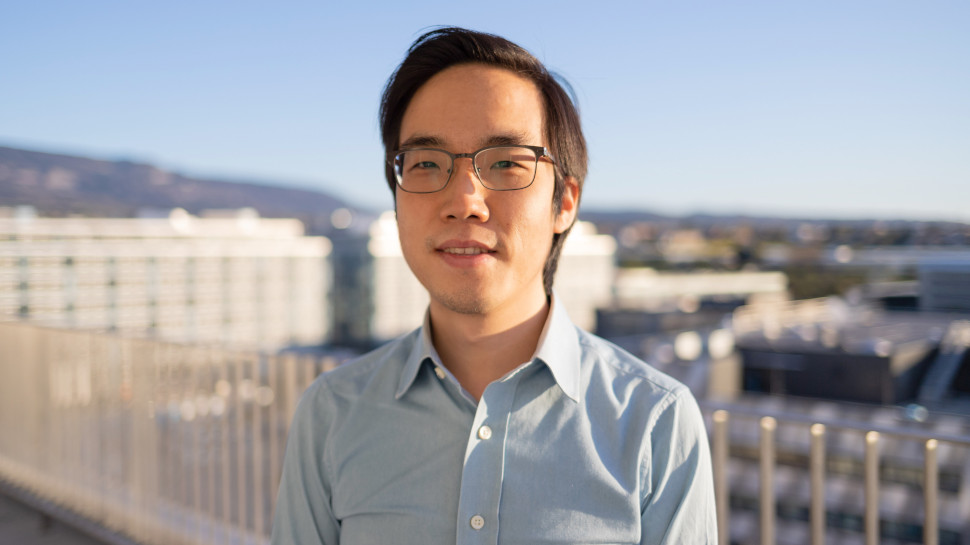

Among the millions of people following the developments was Andy Yen, a particle physicist working at CERN, in Switzerland, which also happens to be the birthplace of the World Wide Web.

After graduating with a Ph.D from Harvard, Yen spent half a decade at CERN specializing in supersymmetry, a field of study concerned with how the universe came to be, why there is matter in the world, and other abstractions.

However, the Snowden revelations pushed Yen to apply his mind to a more concrete problem: building technologies that immunize against the kind of spying conducted by the NSA and defend simultaneously against the covert data harvesting techniques employed by Big Tech.

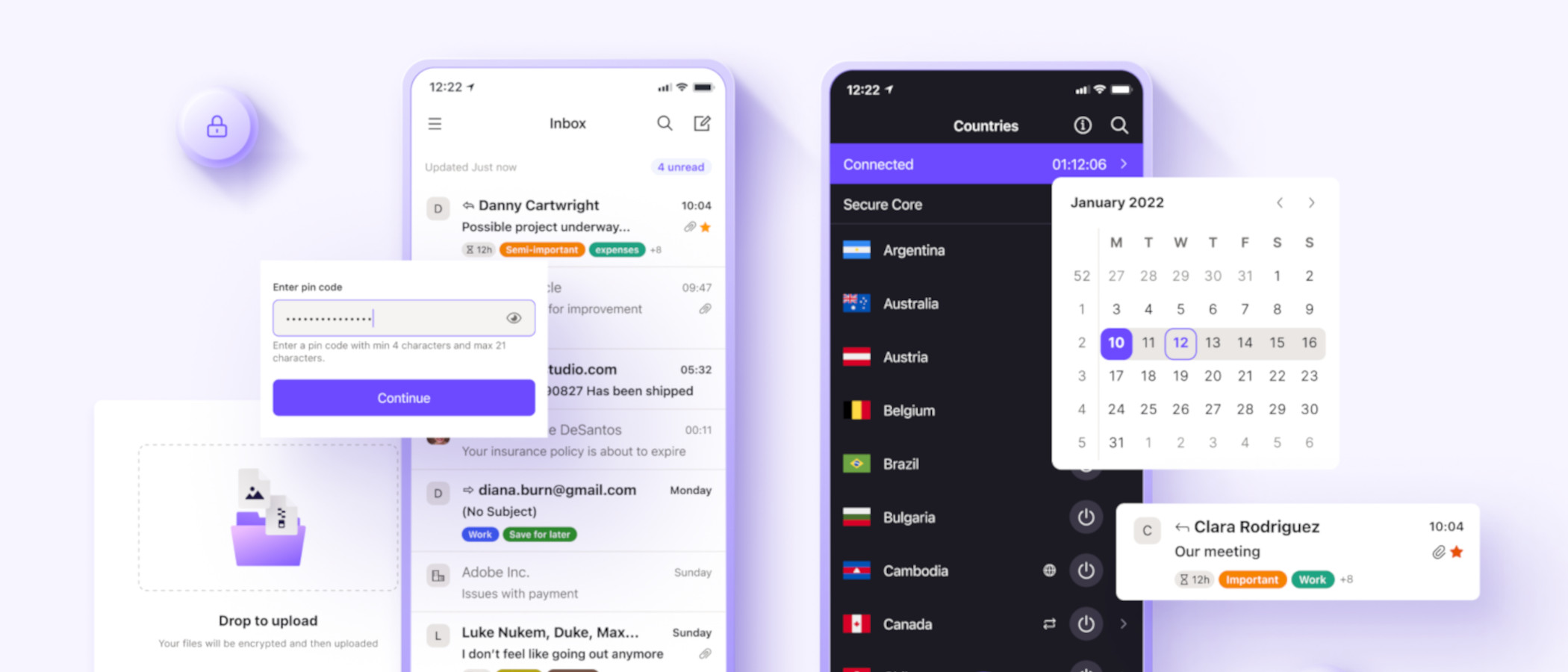

The company he started in 2014 with two fellow scientists - then called ProtonMail, now just Proton - offers a range of privacy-preserving products, from encrypted email to VPN, cloud storage and calendar services. The ambition is to build out a self-contained ecosystem, a safe haven in which internet users can shelter.

In conversation with TechRadar Pro last month, Yen explained that the need for digital privacy has only become more acute since the founding of Proton, as the engines of surveillance become more and more sophisticated.

Sign up to the TechRadar Pro newsletter to get all the top news, opinion, features and guidance your business needs to succeed!

“The web was created as a tool to enable communication across society, but it has strayed from these original ideals,” he told us. “The internet is now a tool to influence the way you think, make you buy certain things and take certain actions. In some parts of the world, it is also a means of oppression.”

“This is one of the defining problems of the 21st century; if we want to preserve freedom and democracy, we need to make sure people have control of their data. Proton’s mission is to return control of the internet to the people.”

You’ve got mail

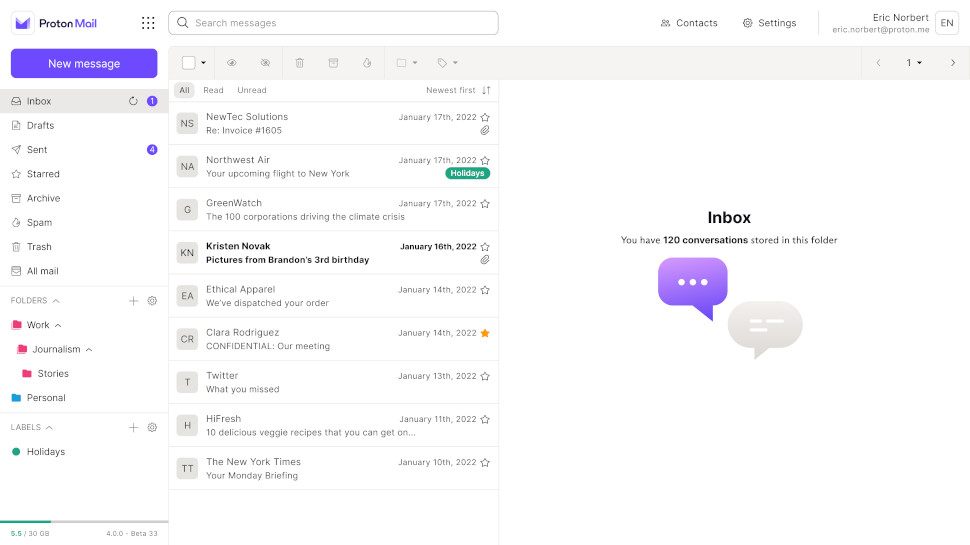

Proton started out with a campaign on crowdfunding platform Indiegogo. The pitch was simple: “encrypted email that anyone can use”.

Originally, Yen and his cofounders asked for $80,000 to spin up the servers necessary to increase capacity and introduce a paid subscription. In the end, Proton raised almost $450,000.

The reason the team chose to prioritize email over another type of service was two-fold: email is the original digital communication technology, pre-dating even the web itself, and it is also the backbone of identity on the web.

“Email is the essence of who you are in a digital world; and your digital identity is arguably the only one that matters today,” said Yen. “It’s not necessarily about [protecting] email data, per se, but rather what control of that digital identity enables.”

For an advertising company like Google, control over the email market is of immense strategic importance. Not only has Gmail historically provided the company with a bountiful source of personal data (this particular harvesting practice was halted in 2017), but it also acts as a foundation on which to “build a profile around you and resolve all that data in a single place”, as Yen puts it.

Asked to articulate why the extensive profiling of web users is dangerous for society, beyond the potential for targeted ads to drive frivolous purchases, Yen sketched out a couple of worst case scenarios.

“There are many possible ends of this timeline,” he said. “One outcome is a Chinese scenario, whereby the data collected by the largest tech companies goes to the government, which uses that data to exercise a huge amount of control over the population.”

“Another is that Big Tech companies grow larger and larger, and take control of all aspects of digital life. As a society, we should not be comfortable with companies having such a large concentration of power and so frequently misusing it, as they have often; the Cambridge Analytica incident is the tip of the iceberg.”

As a function of the popularity of the services provided by Google and the like, Yen believes the original definition of privacy is in danger of being lost and, with it, an all-important anchor point on which people can base their judgements.

“Google and other companies say they care about privacy, but really they are trying to change the definition,” he told us. “Google actually means that no one can exploit your data, except for us. But privacy means that no one can exploit your data, period.”

“The only way we can feel comfortable about our future is through having control over our data - and encryption is a guarantee based on the laws of mathematics.”

The new-look Proton

In recent years, Proton has sought to expand beyond its flagship email service, with the addition of Proton VPN, Proton Calendar and Proton Drive to its portfolio.

The objective is to cultivate an integrated ecosystem of products, such that users will no longer be forced to fall back on the services of Apple, Meta Google and their kind.

Last month, Proton underwent a restructuring to reflect that ambition, collecting its various products under a single brand name. As part of this process, all services were bundled into one subscription package, where previously multiple were required.

The company has promised the integration will also lead to “massive upgrades” in the user experience, courtesy of new optimizations and synergies between products.

“The transformation from individual privacy services towards an integrated privacy ecosystem is an essential step toward building a complete replacement to Big Tech’s offerings,” said Yen, when the restructuring was first announced.

A similar strategy is playing out at other companies in the privacy software business too, like Brave and DuckDuckGo, both of which are actively expanding their respective arsenals with new products.

As for which territories Proton will target next, Yen told us the focus is on readying Drive for a full launch, after which the company will take a read of its customer base and form a new roadmap. There are plenty of potential options (web browser, search engine, password manager etc.), but our money is on encrypted messaging, which was promised as a stretch goal during the initial crowdfunding campaign.

The temptation is to get carried away with the possibilities, however, and Yen was quick to warn that Proton is only just starting out on this path: “Google and Apple’s ecosystems are massive, so we have our work cut out for us,” he said.

There is also some question as to whether the subscription model will be lucrative enough to support an expansion of the scale Yen has in mind, particularly as Proton intends to continue offering free versions of all its services.

One option would be to diversify its revenue streams with the introduction of contextual ads (as opposed to targeted ads) to its platforms; it’s something Yen would prefer to avoid, but may ultimately be forced to embrace.

“In my opinion, you can do advertising and have private services, but there will always be a tension between the two concepts; on a fundamental level, they are not entirely compatible.”

“We know advertising works better when it’s targeted, that’s just the way it is. And to target better, you need to build user profiles and become more and more invasive in terms of the data you collect.”

Whether Proton can sustain itself and its objectives without advertising will depend on its ability to communicate the significance of its mission to a public that historically has been unwilling to compromise on quality of service in the name of privacy.

The winds are changing

There is evidence to suggest the tide of opinion is turning against the technology giants, with the privacy software market expected by one analyst firm to achieve 10x growth by the end of the decade.

However, whether or not the likes of Proton are able to develop a full ecosystem of alternative products will ultimately be irrelevant if market conditions remain as they are today.

Historically, the technology giants have used every option at their disposal to promote their own services by leveraging the strength of their positions in markets ranging from devices and operating systems to app marketplaces, search, browsers and more. The result is a digital market starved of competition.

There are signs that regulators have come to terms with the gravity and urgency of the situation, including recent measures announced by the EU under the Digital Markets Act (DMA).

The DMA seeks to limit the power of so-called “technology gatekeepers” – such as Apple, Meta and Google – whose dominant market position and wealth of resources is said to limit the opportunity for smaller competitors to accrue market share.

It includes measures to prevent gatekeepers from ranking their own products higher in search results and blocking users from uninstalling preloaded applications, and also mandates a level of interoperability between messaging apps.

Asked for his opinion on the EU strategy, Yen described the DMA as “a huge benefit to society, but also a missed opportunity”.

“The EU didn’t quite go far enough, and that’s a big problem, because this is a once in a generation type of legislation,” he told us.

According to Yen, although the DMA will have a net positive effect on the availability of alternatives, the EU made a crucial mistake in failing to tackle the ability for platform operators to “self-preference” their own services.

In practice, the vast majority of users will never switch away from the default, which means companies that compete in the same categories as the largest tech firms are unlikely to make material inroads.

“If antitrust regulation doesn’t tackle defaults, it is only addressing 5% of the problem. That’s really the elephant in the room,” said Yen. “If you don’t tackle that piece, you don’t break the monopoly.”

Breaking the monopoly

A large part of the problem is that regulators are not equipped with the level of technical expertise necessary to unpick the complexities of the issues at hand, Yen told us.

He also believes regulatory bodies need to revise the process for defining new legislation, in line with the speed at which the technology industry is developing.

“The way it used to work is that you would make one giant landmark legislation, then leave it alone for a century. But that old model is not compatible with the world today, which moves so quickly.”

“We need policymakers to be thinking in a different way, with policies updated every one or two years rather than once in a generation. An iterative and therefore more agile approach is what’s needed.”

Challenged on the feasibility of this proposal, given the political headwinds, number of moving parts and need for each piece of legislation to be properly ratified, Yen told us that the big picture needs to take priority.

“It shouldn’t be a question of feasibility, it should be about what’s necessary. Otherwise, the economy will be dominated by just a handful of companies,” he said. “We have the duty and obligation to legislate properly.”

The US has been slower to act than the EU, in part because of the national pride in its famous technology brands, but the wheels are now beginning to turn. Yen is hopeful that landmark antitrust legislation is on the way - and Proton will be ready to pounce.

Joel Khalili is the News and Features Editor at TechRadar Pro, covering cybersecurity, data privacy, cloud, AI, blockchain, internet infrastructure, 5G, data storage and computing. He's responsible for curating our news content, as well as commissioning and producing features on the technologies that are transforming the way the world does business.