Where could BioShock 4 take environmental storytelling next?

It's all about immersion

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

2007’s BioShock works because of Rapture. The once-flourishing metropolis is submerged in stories of individual tragedy, while the cracks in the utopia’s ideology have burst open, letting the salt water and the failure of its people destroy its vision of independence.

After 15 years, the overarching and individual stories of Rapture still work so well because of environmental storytelling – the practice of presenting a narrative, character, or emotion to the player through the game space itself. That said, many games have introduced new ways of using the environment to present narratives since then. So what did the original get right, and what can be learned from more modern examples for the upcoming sequel?

Throughout the game, the laissez-faire ideology of Rapture is baked into its architecture, and into every facet of how the city functioned, and how it fell. The simple act of juxtaposing the entire city’s ideology with its destruction tells the player about the world, with countless smaller stories populating the flooded halls.

In typical immersive sim fashion, many of these stories are told through audio logs. While these work exceptionally well at letting the player explore the environment related to the recording without removing control, it’s a trope that would go on to be emulated to varying levels of success in other games.

I could also wax lyrical about the genius connection between Adam, Plasmids, and the environment itself; the Electro Bolt Plasmid can be used to shock enemies in water and short circuits, while Plasmids themselves require Adam, which links to Rapture's demise.

Devil's in the details

These methods of environmental storytelling still work, but it's been over a decade since BioShock was first released, and since then a number of games have pushed the envelope. So what can the designers of the next BioShock learn from these games when conceiving the series’ next doomed utopia? I’m going to draw on three examples in particular: Dishonored, Outer Wilds, and Firewatch, to explore what BioShock can do next.

While BioShock has multiple ending cutscenes, there’s very little the player can do to make the world change around them. Arkane’s Dishonored does this in spades, as the studio introduced a way for the world to actively react to the player, called the chaos system.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

If you killed lots of guards and innocent people, you’d find the world less hospitable: more guards would patrol the streets, rats would be everywhere, and people would turn you away. If you spared more NPCs, you’d accrue less chaos and find fewer guards on patrol, fewer rats, and you’d get more help from citizens.

BioShock, with its complex urban environments that blend politics with science fiction, could absolutely use this system. Having the player’s decisions, both big and small, contribute to some behind-the-scenes mechanic that influences the state of the world around them would mean that the franchise's next urban environment could do more than tell stories from the past; it could have the player write them as they happen.

The story's in the scenery

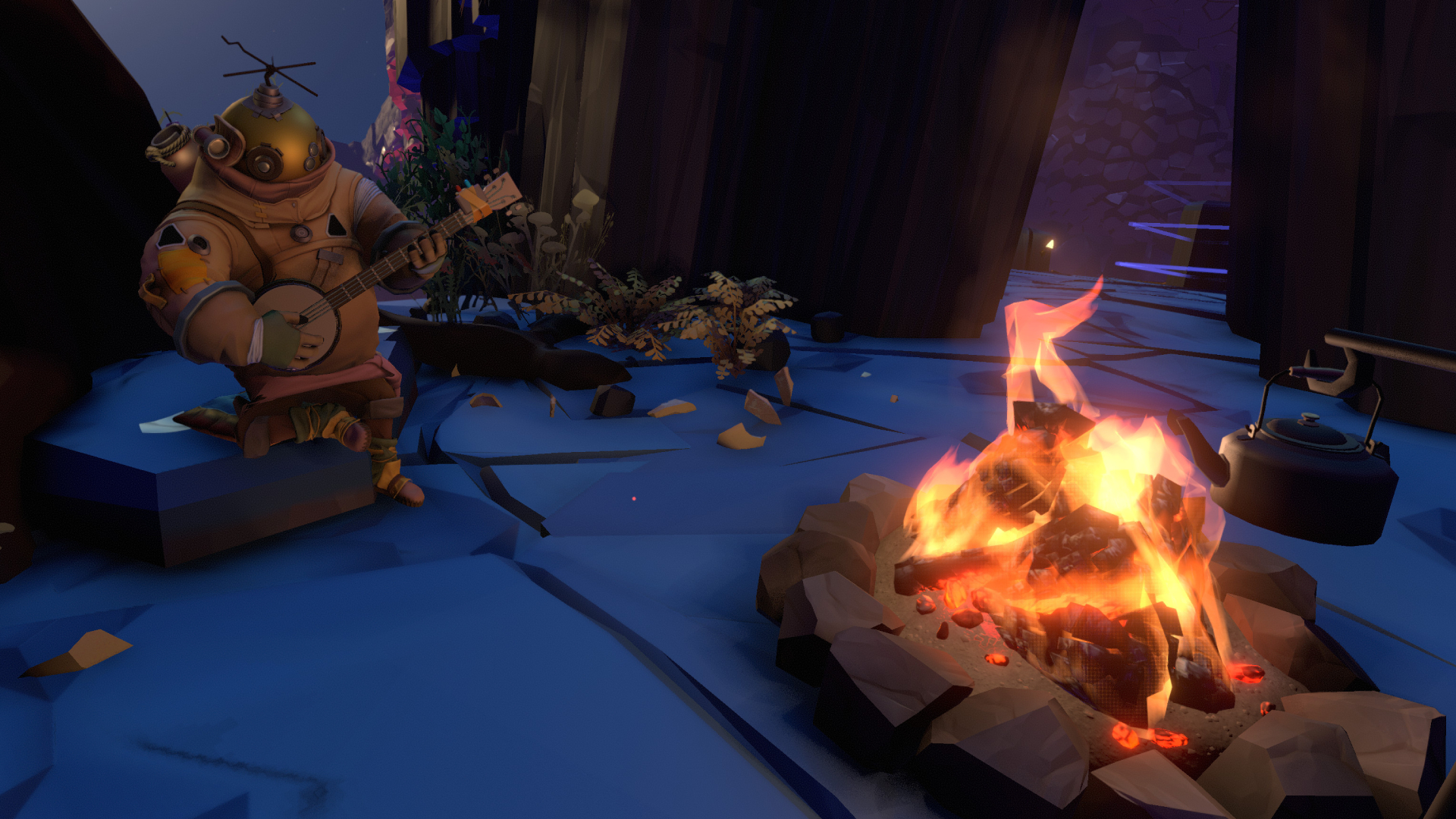

Outer Wilds, on the other hand, can inspire BioShock with its focus on your curiosity that’s often rewarded with not simply an audio log or diary, but with environmental surprise.

The solar system exploration game centers on one major mystery that underpins a series of smaller, but still entertaining, stories, all of which are told through the environment. As narrative designer Kelsey Beachum explained at GDC 2021: "Some of the story is told through found text, but those moments don't deliver the biggest initial hooks. [That text] is meant to be interesting, but it's not going to be as interesting as getting sucked into a cyclone."

The cities of the BioShock universe, like the solar system of Outer Wilds, are inherently interesting places. So the next game in the BioShock series, if built upon a metropolis that constantly poses questions to the player, can harness the player’s curiosity, and tie it up with mechanics uncovered by discovery. The series’ famous wall-scrawling, audio logs, and atmosphere can be combined with a wider freedom of movement, to act as stepping stones for emergent moments, like the ones found in Outer Wilds.

Finally, there’s Firewatch. Without giving too much away, it's excellent at using major and minor environmental changes to reinforce its narrative. Perhaps there’s a hopeful vista pierced by the sunrise or an enclosing darkness that’s only pushed back by the beam of a torch. Firewatch uses the environment to excellent effect, both to underpin the story via ongoing two-way radio conversations and to highlight an oppressive atmosphere. The original BioShock is also driven forward by a two-way radio conversation and an oppressive atmosphere, but the next game could follow Firewatch, and build its areas/levels to suit how the mood it wants to convey.

BioShock 4 has a difficult road ahead of it. While that road was paved by the 2007 original. It’s been repaired and improved by 15 years of environmental storytelling innovation that the game's designers will need to acknowledge and draw upon. If developer Cloud Chamber can channel the science fiction and philosophical questions presented by the series at large, while finding ways to embed the environmental storytelling into how players interact with the game, we could be looking at a truly incredible sequel.