“I’m an optimizer,” says Trent Oster, now founder and CEO of Beamdog, once the director of Neverwinter Nights, Bioware’s landmark RPG which launched 20 years ago today. “When I look at something, I'm like, ‘I think I can do that better’. And the problem I'm trying to solve is that it takes years to create content, and it takes minutes to play it.”

This was the problem Bioware encountered during the development of Baldur’s Gate, a game which, it has been estimated, took 90 years’ worth of working hours to build. Baldur’s Gate is a sprawling and highly flexible RPG, frequently regarded as one of the greatest ever made. But it is ultimately designed to tell one story. A very big story, but a single one regardless.

After wrapping up Baldur’s Gate, Bioware decided it wanted the player to enjoy not just one story, but thousands. “The democratization of game design,” Oster says. “Allowing people to go in and build their own adventures and share them with their friend group.” The result would pioneer many of the concepts that power some of today’s biggest games, combining the community-driven creation that would make Skyrim and Minecraft such enduring phenomena, with the curated shared-world experience that attracts thousands of players to Destiny and GTA Online. Neverwinter Nights was wildly ambitious, and it would push Bioware to the limit, with long-lasting effects for both the studio and Oster personally.

Development on Neverwinter Nights began before the launch of Baldur’s Gate and its millennium year sequel, when Oster sat down with fellow Bioware co-founders Ray Muzyka and Greg Zeschuk. “Greg and Ray and I got down to talking and they wanted to do something new,” says Oster, who at the time was working on MDK 2 while also overseeing the art department of Baldur’s Gate. “And we came up with this idea of like, ‘What if we built everything that was in the D&D box?’ So it’s got to be an adventure. It’s got tools, and it’s got everything that comes in the box.”

Box fresh

Bioware’s idea was a full digital adaptation of D&D, one that gave you not only the rules of the RPG, but the capacity to build your own campaigns. The fact it became Neverwinter Nights was mostly serendipity. “We wanted somewhere on the Sword Coast, but we wanted to be differentiated from Baldur’s Gate,” Oster says. “At the same time, Interplay was going to publish it and was like, ‘Hey, we’ve got the rights to this [early 90s MMO] Neverwinter Nights’.” In the end, Neverwinter Nights would be published by Atari, who acquired the rights to adapt Dungeons & Dragons in the middle of the game’s development.

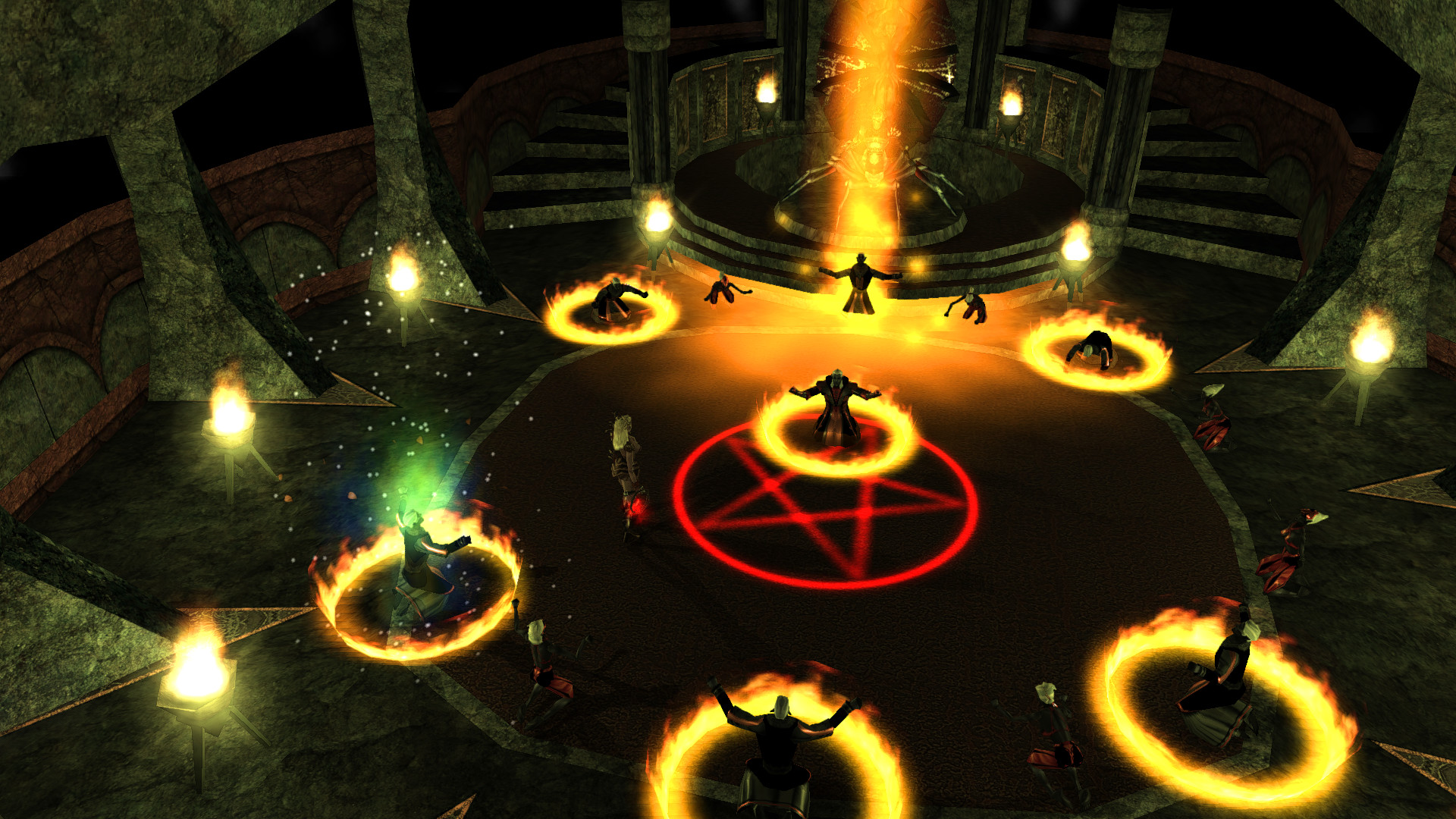

As well as trying to build the entire D&D toolset, Bioware also decided that Neverwinter Nights would be a full real-time 3D game, and not isometric 2D like Baldur’s Gate. This made it difficult to attain the level of detail seen in Baldur’s Gate’s lush pre-rendered art. So instead, Bioware took advantage of the darker character of Neverwinter, using it to make the most of what 3D could offer in 2002. “We really leaned into that,” Oster says. “We were like, ‘OK, in Neverwinter Nights, a character has to be recognisable from their silhouette. So the shapes, like spikes on shoulder pads, really dominated the art look.”

We itemised a huge plan for the project, and it came out to five years

Making the whole D&D box work across turn-of-the-millennium Internet for up to 64 players was a huge undertaking – technically way more ambitious than Baldur’s Gate. Bioware was under no illusions about the effort Neverwinter Nights would take to realise. “We itemised a huge plan for the project, and it came out to five years,” Oster says. “We present[ed] this to Greg and Ray, and they were like, ‘No one will ever pay for a five-year development cycle.’” So Oster went back to the drawing board with lead programmer Scott Greig. “We cut it back and we showed them a three-year plan, and that’s the one we signed with Interplay.”

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

Five year plan

Looking back, Oster describes the decision to go with a three-year plan as a “fundamental mistake”. This wasn’t because it compromised the project itself. Unusually for a game of this size, Oster says that “over 90%” of what they had planned to include in Neverwinter Nights was present in the final version.

Instead, the three-year plan was a problem because development ended up taking five years anyway, as the features selected to be cut ultimately proved vital to the game’s function. Consequently, the team worked a five-year project under the pressure of getting it done in three. “For three years I was working six days a week, probably 10 to 12 hour days pretty steady," Oster says. “And then in the last year it was seven days a week. In the last two weeks, I put in 212 hours. Nobody told me to do that. I saw it as the only way to succeed.”

One of the few ideas that didn’t make it into Neverwinter Nights was a “character vault” that would persist online. “You would basically check your character in and check them out so that you can play verified adventures, and we could essentially police your progress so you couldn’t create a module and give yourself 200 million experience points,” Oster says. “But we took that character vault and instead of doing one global one, made local vaults.”

Neverwinter Nights was a huge success, selling a million copies within a year of launch. But the impact of its development on Oster and the team was profound: “I was an emotional wreck for a while after it. I just couldn’t handle things. Disney movies made me bawl like a baby.” Oster estimates it took around eighteen months before he was able to put in a normal working day again. But it wasn’t just Oster who was affected by that three-year decision. “We didn’t tell people they had to crunch,” he says. “But we let them see the work that had to get done. A lot of people stepped up and put in a lot of time.”

I ask Oster why Bioware didn’t return to a five-year plan after Baldur’s Gate proved the studio’s ability to realise these projects. “We didn’t think we were great,” he says. “We thought we got lucky. We made a Windows 95 game, one of the first Windows 95 games. We just happened to make it when our publisher of our previous game had the D&D licence. There was a lot of luck that just happened to fall on top of each other.”

Unforgotten realm

This sense of being fortunate underdogs continued well into the 2000s. “Even after Baldur’s Gate 2, after Neverwinter Nights, there wasn’t a real sense of entitlement at Bioware,” Oster says. “There was a real, ‘We work hard to make good games. And if we make really good games, hopefully our fans will like us.’”

It came at a substantial human cost, but Neverwinter Nights succeeded in what it set out to do. The community that sprung up around it embraced the toolset, and has spent two decades building some truly impressive campaign modules for the game, like the Swordflight Saga, and the Aielund Saga, to name just a couple. But the toolset was also twisted in ways Bioware didn’t anticipate. “It was used in a lot of university programmes and in a number of high-school programmes to teach game development,” Oster says. The game was even used by MIT for an AI experiment to simulate how rumours propagate through a community.

Beyond its financial success, perhaps the most significant impact Neverwinter Nights had on Bioware’s future was as an unofficial recruitment tool. “It really shows, ‘This is how to make a Bioware RPG,’” Oster says. “And that became the hiring pipeline for designers for probably five, six years at Bioware. It’s like, ‘Oh, you want to be a technical designer at Bioware? Where’s your Neverwinter mod?’” Oster cites two Bioware designers who were recruited from the Neverwinter modding scene – Georg Zoeller, who worked on titles like Mass Effect and Star Wars: The Old Republic, and Yaron Jakobs, who is still at Bioware today.

Oster himself left Bioware during the development of Dragon Age, forming his own company, Beamdog. But he went back to working on Neverwinter Nights for Beamdog’s remastered version of the game. I asked him about his experience returning to the shadowy streets of the Forgotten Realms city; whether it was any easier to work on a second time around.

“It’s never easy because, especially games from that era, in order to make them perform, you had to be clever,” he says. “And when you’re clever, technology advances in that 10 year period, where ‘clever’ is now the wrong way to do things.” Among other challenges, Beamdog had to completely rebuild the game’s renderer, which they took “a couple of runs at” in order to have it perform optimally on both console and PC.

Never again?

Launched in 2018, Neverwinter Nights: Enhanced Edition found an audience all over again. This isn’t especially surprising. While many games have taken important lessons from Oster’s opus, no other RPG occupies quite the same space. Neverwinter Nights hasn’t seen a spiritual successor the way that Baldur’s Gate has, in Pillars of Eternity. The closest analogue is probably Larian’s Divinity: Original Sin 2, which launched with its “Game Master” modding tools. But Larian’s RPG isn’t associated with D&D.

Perhaps the potential audience for a new Neverwinter Nights is still happily playing the original. Or perhaps, as Oster puts it, “If somebody else tried to build that game today, it would take them 10 years.” Either way, the lack of a successor clearly bugs Oster, and despite the cost of making Neverwinter Nights, he’s still clearly infatuated with the principles behind it. “I’m so tempted personally to take another run at it,” he says, smiling mischievously. “Again, I’m an optimizer. Can I make it without spending 10 years doing it? I haven’t figured it out. Yet.”