Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Originally released in 2002, Medieval: Total War is a game that sits in two shadows. The second title from strategy maestros Creative Assembly, Medieval's legacy is sandwiched between the dazzling innovation of 2000’s Shogun: Total War, and the world-conquering magnum opus that was 2004's Rome.

But the importance of Medieval's contribution to the series cannot be overestimated. Not only was it the game that established the scope and structure that would be carried forward through the series, it also saw Creative Assembly begin to transform as a company – evolving from a fairly loose collection of designers who struck gold with Shogun, to a more formalized development studio that would ultimately go on to create Rome.

"Shogun was pretty much about just getting it together to make it a game," says Ian Roxburgh, game director at Creative Assembly. In the early 2000s, Roxburgh had arrived at the studio as a PR manager, from his previous job as a journalist on PC Gamer. "When I joined the company, at that point it was about how to make that formula more watertight, get all the things that could have been done better, better."

The first decision the studio had to make was where, or more specifically when, the sequel would be set. "I remember we were looking at a more Renaissance [theme]," says Greg Alston, now project art director at Creative Assembly, who worked in varying roles as an artist on Medieval. "At one point, we were just saying, 'Right, let's do some units in the Renaissance period.'"

Ancient Rome was also discussed as a setting for the sequel, but was ultimately dismissed due to the technical complexities involved with representing the era. "Technically there are some things in Rome that wouldn't have been easily achievable with the Shogun engine," says Joss Adley, principle UX director at Creative Assembly, who worked on Medieval's UI and maps. "Complex war engines and things like siege equipment, chariots and testudo formations would obviously be problematic to do with sprites."

Crusader things

In the end, the studio settled on the medieval era, which shared some feudal themes with Shogun and had broadly similar army construction – yet had enough differences to justify a sequel. But the game wasn't known as Medieval at this point. Following on from the warrior-centric naming convention of Shogun, Medieval was originally intended to be titled Crusader: Total War. This changed midway through development due to a world-changing event. "Shortly after I joined the company, 9/11 happened," Roxburgh says. "George Bush came out and started talking about, 'It's a crusade against this, that and the other'. And we thought, 'Hang on, we don't want to be associated with this.'"

We had the time to go deeper across multiple cultures, multiple factions within those cultures, and do them justice

Joss Adley

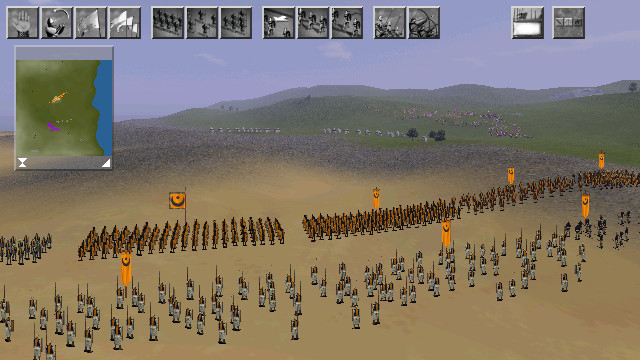

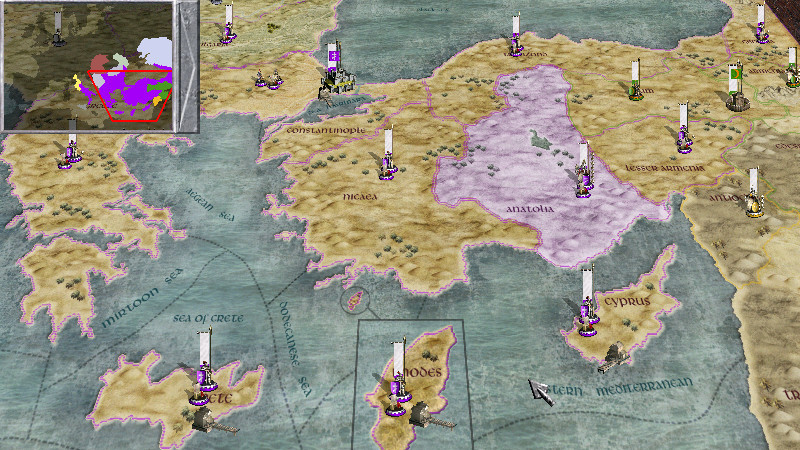

The new title also made more sense, better reflecting the greatly expanded scope and cultural diversity of the sequel. Whereas Shogun was restricted to Japan's larger islands, Medieval's map spanned the whole of Europe, a large chunk of the Middle East, and portions of North Africa. Where Shogun took place over a period of 150 years, Medieval charted events over almost four centuries. And where Shogun's feudal Japanese society was a mostly isolated monoculture, with similar factions fielding similar armies, Medieval had to represent numerous cultures, nation-states, religions, and militaries.

Sign up for breaking news, reviews, opinion, top tech deals, and more.

It was a massive expansion upon the previous game. But the expansion was made possible because the technology was already in place. "A lot of the big questions about how the gameplay would fit together, with the two halves [between the turn-based campaign and real-time battles] had already been answered. That was all validated and people liked that," Adley explains. "We had the time to go deeper across those multiple cultures, multiple factions within those cultures, and do them justice."

Siege the day

Alongside broadening the scope of Medieval, Creative Assembly also wanted the player's conquest of the world to be a richer, more simulated experience. "The campaign in Shogun was pretty pared back,” Adley says. “We added some gameplay depth to Medieval." One of these features was a Vices and Virtues system, whereby characters in the game could develop specific traits across the campaign, affecting their overall attributes. Virtues includes traits like "Famous Warrior" and "Great Leader", while Vices could include "Murderer" and "Cowardly". This system predates a similar one that formed the backbone of the Crusader Kings series, which would become famous for its detailed simulation of character relationships.

I was kind of playing LEGO with the [map] editor. Trying to create these massive sprawling castles and populate them with troops

Ian Roxburgh

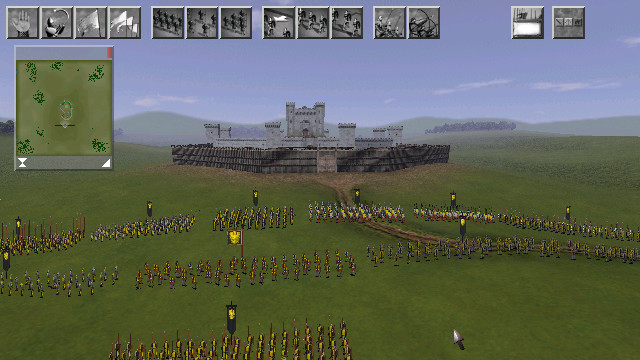

The headline feature of Medieval, however, was its castle sieges. New to the series, these let players assault looming stone fortifications with a combination of troops and trebuchets. "We already had 3D scenery and 3D buildings from Shogun," Adley says, "So it was really a new pipeline to get [them] destructible, and then doing that in a modular fashion so that walls and towers could be destroyed individually." The sieges were also a crucial element of Medieval's marketing. "I was kind of playing LEGO with the [map] editor," Roxburgh says. "Trying to create these massive sprawling castles and populate them with troops, to be able to get assets to send out to magazines."

Before Medieval, Creative Assembly had little cause to consider marketing its games. The studio had primarily worked on sports games for EA, which also published Shogun. But CA had switched publishers to Activision for Medieval: Total War, and played a more prominent role in selling the game to players. This meant the developers had a lot to learn about the more public-facing, business side of game development.

Roxburgh recalls one incident that occurred when a studio director showed off Medieval to PC Gamer US. "It worried me because he had literally taken a build of the game on a disc, would go out, install it on someone's machine and just randomly load up a battle," he says. "And there was a bug where [the soldiers] were just floating 100 feet up in the air. I thought, 'Oh my god, you can't be showing our game off to journalists without having prepared.'"

Feudal far between

This somewhat cavalier attitude reflects Creative Assembly's broader attitude toward organization at the time. "It was a much looser, smaller team structure, with less clearly defined roles," Adley says. "It wasn't uncommon for an artist to be doing a bit of 3D modeling and then come across to do some icon work, then be asked to animate for a couple of days. Everyone did a bit of everything, which was OK for working on a small-scale game, but not really sustainable for a larger project."

Indeed, it was during Medieval's development that the studio began to realize a more formal structure was needed, which would gradually become established as the team wrapped up the project and focused on its next game, Rome.

Like Shogun before it, Medieval was a success and has since become a fan-favorite, to the point where Creative Assembly released a direct sequel to the game – Medieval II – in 2006. But two decades on from Medieval, and sixteen years on from Medieval II, the big question is whether the developers have thought about launching a third crusade. "Of course we've considered it. It is constantly on the radar because we know it's something the fans really want," Roxburgh says. "As a studio, it's something we will do at some point, I'm sure."