Weren't we supposed to have 3D printers everywhere by now?

One day our 3D prints will come

In March, for example, researchers at the University of California demonstrated a way to intercept 3D printing plans by simply listening to the printer. The results are 90% accurate, which is impressive for something that simply involves recording sounds on a smartphone.

The reason for such research is that 3D blueprints are actually rather hard to get hold of: they tend to be heavily encrypted, and some are scrambled in such a way that illegitimate copies will contain glitches. Because of this, mass 3D-printing piracy hasn't happened so far.

Intellectual property infringement does happen – search the Pinterest of 3D printing, Thingiverse, for Star Wars and you'll get models such as the Fillennium Malcon – but copying a physical object isn't as easy as copying an MP3 music file.

Copying music is instant and doesn't cost anything, because all you're doing is copying a file. Making a 3D-printed replica of something takes a lot of time, and the raw materials cost money.

3D printers don't have the economies of scale that, say, Hasbro has when it's making Star Wars toys on a production line, even if you have lots of them. So for many items it's cheaper and easier to order a no-name Chinese knock-off on eBay than to pirate it.

We didn't choose Hasbro at random either: it's embracing 3D printing, which suggests it isn't particularly worried about it being an existential threat.

The Japanese firm teamed up with 3D printing firm Shapeways to create a range of 3D-printable toys including Star Wars, Transformers, Scrabble and My Little Pony.

Get daily insight, inspiration and deals in your inbox

Get the hottest deals available in your inbox plus news, reviews, opinion, analysis and more from the TechRadar team.

It even offers Superfanart , a platform for people to sell their own 3D-printed designs.

In Hollywood, meanwhile, 3D printing is something they're watching carefully at the moment rather than sending the lawyers to stop: someone who designs a replica lightsaber based on a movie trailer is more likely to be a super-fan than a pirate.

So 3D printing isn't destroying the capitalist world... yet. But is it manufacturing guns?

Go directly to jail

In 2013 we saw the first demo of a 3D-printed gun, the Liberator. The US Directorate of Defense Trade Controls demanded that Defense Distributed, the Liberator's creator, remove the CAD files from the internet, but inevitably they're still floating around.

You'd expect the US to be all over 3D-printed firearms, but they remain a niche interest, possibly due to the Undetectable Firearms Act, which was renewed in 2013.

That makes it an offence to own any firearm that can't be spotted by a metal detector, and there were calls to make its provisions even tougher to outlaw 3D-printed weapons altogether, although so far 3D-printed guns made of metal are proof of concept rather than production reality.

It's also illegal in most of the US to manufacture guns without a licence.

In the UK, excited headlines about ISIS getting 3D-printed AK-47s have led to calls for compulsory registration of 3D printer purchasers, although such registration hasn't made it to the statute books yet.

3D-printed guns are illegal under the 1968 Firearms Act, and the Act was amended in 2013 to cover components as well as complete weapons.

It's illegal to own or manufacture a 3D gun in the UK, and the penalty can be 10 years in prison.

To date nobody has been caught with such a weapon, despite more excitable headlines: stories of a 3D-printed gun found by Manchester Police in 2013 turned out to be false – the 'gun' was just replacement parts for a 3D printer.

The price is (nearly) right

While 3D printers haven't quite reached the $100 mark (the $100 Peachy Printer on Kickstarter, which was expected to ship in December 2013, still hasn't, with the company now broke amid allegations of theft by one of its founders) prices are plummeting – for example, XYZPrinting's Da Vinci Jnr is currently $329 (£230, AU$435) on Amazon.com.

But really affordable 3D printers are limited by two things: the 'golf ball' rule and the lack of color.

The golf ball rule is a rule of thumb: if something isn't small enough to fit inside a golf ball, it isn't a good candidate for 3D printing. And most affordable 3D printers are designed to print using a single nozzle, not the multiple nozzles necessary for multi-color objects.

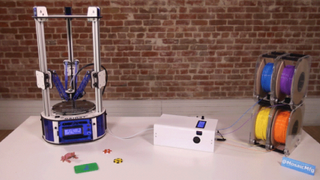

Printers capable of good quality multi-color printing are very expensive, although a lower-cost option, the $999 (£700, AU$1,370) Palette, brings a variety of hues to any 3D printer.

For consumers, 3D printing is currently reminiscent of the early days of digital photography: it's enormous fun and tremendously exciting, but the hardware is limited and expensive.

Right now it's one for the hobbyists and the early adopters, and it's likely to stay that way for a few years yet. But in industry, medicine and aid work, it's already doing amazing things.

Writer, broadcaster, musician and kitchen gadget obsessive Carrie Marshall (Twitter) has been writing about tech since 1998, contributing sage advice and odd opinions to all kinds of magazines and websites as well as writing more than a dozen books. Her memoir, Carrie Kills A Man, is on sale now. She is the singer in Glaswegian rock band HAVR.